Space Junk Could Be This Company's Treasure

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. —“Within a few decades, we may not be able to use space anymore," Nobu Okada, founder and CEO of the Singapore-based company Astroscale, told the crowd gathered at the New Space Age Conference held on March 11 here at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Sloan School of Management.

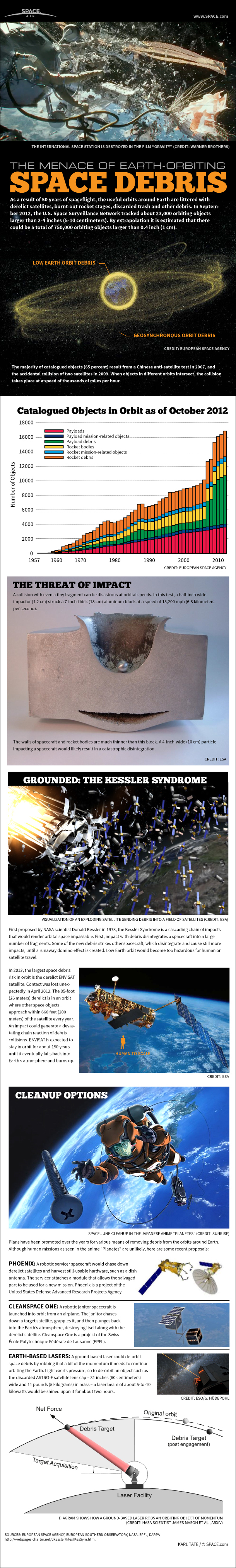

Already, hundreds of millions of pieces of debriszoom around Earth at speeds of up to 17,900 mph (28,800 km/h). This cloud of junk presents a hazard to existing spacecraft, and the problem is set to get worse, because space is about to get a lot more crowded. In the next five to 10 years, for example, companies including SpaceX, LeoSat, and OneWeb plan to launch more than 15,000 satellites into low-Earth orbit (LEO), primarily to an altitude of between 500 miles and 750 miles (800 to 1,200 kilometers) above the planet, to provide global internet service.

Okada has a plan to deal with the debris, though. He said he wants to work with governments and businesses to build a retrieval mechanism into spacecraft before they launch. Should a satellite fail prematurely — and about 5 percent or more likely will — an Astroscale spacecraft would launch to snag the derelict satellite using the built-in component and dispose of the satellite. The company has already raised $53 million in funding and, since 2015, has operated a manufacturing facility in Tokyo. [Space Junk Cleanup: 7 Wild Ideas]

What the company learns from its so-called "end-of-life" ventures could eventually help Astroscale build an "active debris removal" plan for the future, Okada said.

"Is there anyone who still doubts that commercial space debris removal is feasible?" Okada asked the crowd.

A few people raised their hands. If doubts are subsiding, it may be because more and more government and university research teams are investigating how to deal with space junk. At last year's European Conference on Space Debris, for example, several groups proposed their far-out methods. And later this year, a test mission called RemoveDEBRIS — which is led by the Surrey Space Centre in the United Kingdom and supported by a consortium of European industry and government organizations — will test a "chaser" satellite equipped with a harpoon and a net.

But it's been difficult to convince investors that such a business could turn a profit. The circling hodgepodge of defunct satellites, fairings, fittings, adapters, rocket motor effluent, bolts and any other number of miscellaneous parts resulted from programs that did not budget for cleanup costs, Okada said. And even if they had, the technology required to spot a piece of junk zooming through space, intercept it, capture it as it topples end-over-end and dispose of it has yet to be demonstrated in space. [Space Debris: Photos of Junk in Space]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But private companies eager to launch future constellations of satellites are concerned about the growing field of orbital debris and are motivated to avoid contributing to it, Okada said. That's where Astroscale comes in. For a small, yet-to-be-determined fee, Astroscale will work with satellite companies ahead of launch to affix a small, lightweight plate with a ferromagnetic coating to the craft's exterior. If the satellite fails before its nominal end of life, Astroscale will launch a retriever satellite that will track the dead craft and attach to the plate using a robotic arm with a magnetic end. Once secured, the two craft will plunge into Earth's atmosphere and burn up together.

Chris Blackerby, Astroscale's chief operating officer, told Space.com that the current plan is to use one retrieval craft per piece of debris. Blackerby said that a reusable chaser spacecraft would be ideal, but it isn't yet economically viable to achieve the change in velocity required for capturing debris, bringing it to a lower orbit where it would quickly degrade and then going back to hunt for more debris.

"It takes so much propulsion to change velocity, and so much time, the economics of doing that aren't there yet," he said.

But future technologies, such as refueling stations in orbit or advanced electric propulsion, could change the business model, Blackerby said.

In 2019, Astroscale will launch a demonstration mission called ELSA-d, which stands for End-of-Life Service by Astroscale-demonstration, the company said. It will consist of a "dummy" satellite meant to represent a piece of space junk and another satellite designed to retrieve that junk. Once in orbit at between 310 miles and 370 miles (500 to 600 km) above the Earth, the two craft will separate. The retrieval craft will attach to and release the dummy craft three times in a kind of space waltz. After the dance is done, the two will degrade together in Earth's atmosphere.

If all goes well, Astroscale hopes to begin mass producing similar satellites by 2020, Okada said. "Our mission is crystal clear — to secure spaceflight safety," he said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tracy Staedter is a freelance science writer, editor, writing coach, and consultant with an eclectic career spanning over 20 years. She's has covered a range of science and technology stories from astrophysics to zero waste. She worked on staff for such online sites and publications as Space.com, LiveScience.com, Astronomy, Scientific American Explorations, MIT Technology Review, DNews, and Seeker. She also wrote the illustrated book, Rocks and Minerals (part of the Reader’s Digest Pathfinders series) and founded the Fresh Pond Writers workshop for fiction and creative nonfiction writers.