Where Will Debris from China's Falling Space Station Land? Here's the Latest Update

Update for April 1, 4:45 pm EDT: New re-entry forecasts by the European Space Agency and Aerospace Corp. have shifted the time of Tiangong-1's expected crash to between late Sunday and early Monday (April 2). ESA officials are targeting a crash time between Sunday evening and early Monday morning. The latest update from the Aerospace Corp. forecasts an 8:30 p.m. EDT (0030 April 2 GMT) crash, give or take 1.7 hours.

At the time the story below was written Saturday (March 31), Tiangong-1 was expected to fall into the Pacific Ocean. Earlier on Saturday, a 7:30 p.m. EDT target on Sunday would have put the space station's point of descent around Africa – so it still remains highly uncertain. "I wouldn't put a lot of faith in that particular number, but it will probably move around and change," Andrew Abraham, a senior member of the technical staff at Aerospace Corp, told Space.com today. "If we're only off by a minute, it would move the location by hundreds of miles."

Abraham added that updates to Tiangong-1's trajectory show a trend of it delaying its re-entry time even further, so it's possible the station may fall later on April 2 – depending on the activity of the sun, and the tumbling of the space station. [China's Falling Space Station: Everything You Need to Know]

Original story: While it's still hard to predict exactly when and where the doomed Chinese space station Tiangong-1 will fall this weekend, the latest prediction from Aerospace Corp. says the debris will most likely descend into the Pacific Ocean Sunday (April 1).

As of late Friday, Tiangong-1 was predicted to fall from space on Sunday at 12:15 p.m. EDT (1615 GMT), give or take 9 hours. Earlier in the day, when the space station's fall was forecast for 12 p.m. EDT on Sunday, an expert told Space.com that earlier prediction would have seen Tiangong-1 begin its re-entry over Malaysia, and rain debris downrange into the Pacific Ocean.because the space station is moving in its orbit across the equator, toward the north.

"It should be a show for anybody on a boat," Aerospace Corp.'s Ted Muelhaupt told Space.com. He runs a center for orbit and re-entry debris studies at the California nonprofit research organization, which is tracking the descent of Tiangong-1. [Track Tiangong-1! Use Our Satellite Tracker Here by N2YO]

Real-time tracking information for Tiangong-1 is available here from Aerospace Corp.'s Center for Orbital and Debris Reentry Studies.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

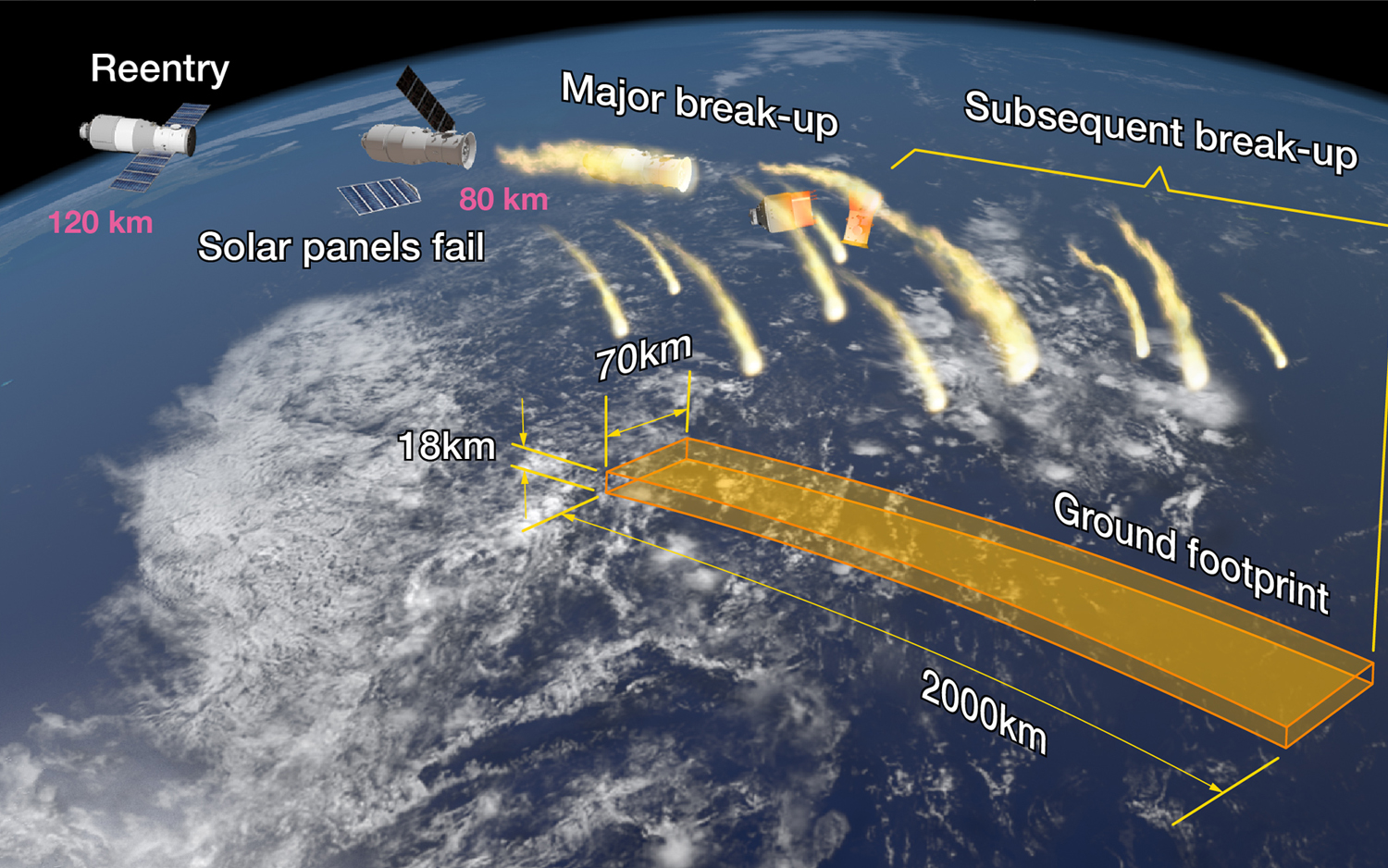

Muelhaupt said people around Malaysia can expect to see fireballs similar in magnitude to the spectacular planned breakup of ATV-1 "Jules Verne," a European cargo freighter that returned from the International Space Station in 2008. In 2015, ESA published a video from a chase plane showing the dramatic, fiery breakup of ATV-1 over the Pacific Ocean. ATV-1 was similar in mass to Tiangong-1, which is 9.4 tons (8.5 metric tons).

While the amount of space debris generated from Tiangong-1 is tough to predict, roughly 220 to 440 lbs. (100 to 200 kg) may survive the fall through the atmosphere, Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell told Space.com sister site Live Science. That's less material than what was left behind after the 1979 breakup of the 100-ton (90.7 metric ton) Skylab, which unexpectedly threw debris into rural Australia during re-entry.

Prediction simulations

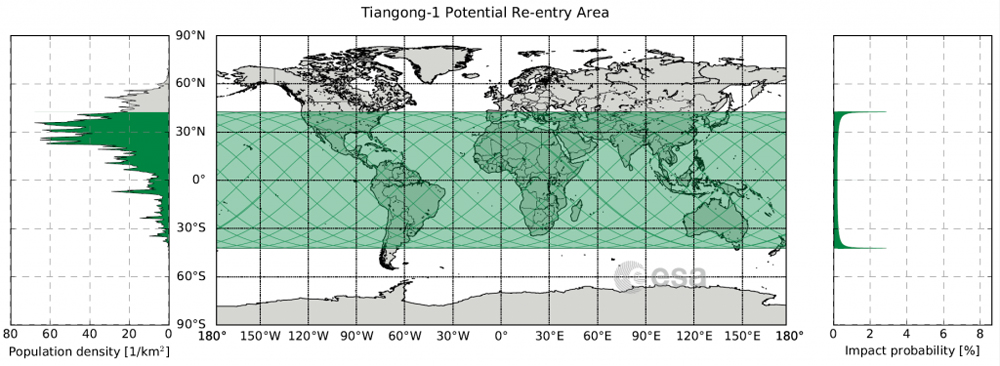

Although the Pacific Ocean is the most likely location for Tiangong-1's demise, Muelhaupt emphasized it's hard to say where the station will re-enter Earth's atmosphere. The station is constantly orbiting Earth at an inclination between 43 degrees north and 43 degrees south latitudes, which includes the United States and much of the civilized world.

"The probability along the ground track is still pretty flat for the entire length of the track," he explained. This means that although Malaysia is where the probability of re-entry peaks, it's only a low spike compared to all of the other predicted points of re-entry.

At this point, Aerospace Corp. is more comfortable saying where the station likely will not re-enter; the Amazon, for example, is a "pretty safe" location, Muelhaupt said. He compared the situation to trying to predict the odds of who will won a lottery.

"One of the things about probability — just because you bought two lottery tickets, doesn't mean you have a much higher probability of winning than someone who bought one," Muelhaupt said. He added that the chance of any particular location "winning" the Tiangong-1 re-entry lottery — of experiencing space debris from the falling space station — is extraordinarily low. But as geographical regions of possible space debris are eliminated, the other locations on Earth will have a slightly higher probability of debris.

As Tiangong-1 descends closer to Earth, predictions of its fall location will improve. No one will know for sure where the space station will fall, however, until it actually comes down. "By tomorrow afternoon, we'll probably know within two to three orbits where it will come in," Muelhaupt said. [Chinese Space Station's Crash to Earth: Everything You Need to Know]

Multiple models

To create its Tiangong-1 re-entry prediction, Aerospace Corp. uses no less than eight prediction methods. It tries to find a consensus between the models for its published estimates.

"Each one [model] makes slightly different assumptions, with slightly different orbit propagators," Muelhaupt said. "Depending on how the model is written, you have to make guesses about different things. Each of them comes with a slightly different perspective. There is no one way to model these things, so we run a basket and look at where we think the consensus is."

For example, one of the models uses a Monte Carlo simulation — a computer simulation that shows a range of possible outcomes, and the probability of each outcome occurring. Another model emphasizes one particular outcome, or "truth," over all others, Muelhaupt explained. Some models assume breakup occurs at a slightly higher altitude than others, which also affects Tiangong-1's predicted fall.

"We base all public statements on publicly released information, run through each of the different models, average the results and look for consensus," Muelhaupt said, but said even that can produce challenges.

"Occasionally we get one model that is an outlier. For example, it might put more weight on a later prediction, vs. earlier measurements … that's why we run multiple models. Every time you think you've got all of the guesses right, you are wrong. So it is best to get multiple opinions."

One important factor in making predictions is the geomagnetic index — the amount of activity generated in Earth's vicinity from the sun. The sun's energy, as it strikes the Earth's atmosphere, can make gases balloon higher and increase the density at more elevated altitudes. The sun's activity in recent days, however, was quieter than expected.

The sun's quiescence keeps delaying the time of Tiangong-1's expected re-entry, because it means the Earth's atmospheric density near the station is lower than expected. That's made a huge difference in re-entry predictions. Just three days ago, Muelhaupt noted, Aerospace Corp. predicted a re-entry time of 0200 GMT April 1 (10 p.m. EDT March 31). That's 16 hours earlier than the current expected re-entry time.

Tiangong-1 launched in 2011 and hosted two crews of taikonauts (Chinese astronauts) in 2012 and 2013. China subsequently lost contact with the space station in 2016, and Tiangong-1 has been falling to Earth ever since. Tiangong-1 is the first Chinese space station, and a successor — Tiangong 2 — began operations in 2016.

Editor's note: This story was updated at 4April 1, 4:45 p.m. EDT (2045 GMT) to include the latest re-entry forecasts from the European Space Agency and Aerospace Corp.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.