'2001 A Space Odyssey' 50 Years On: Q&A with Computer Scientist Stephen Wolfram

In April 1968, Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke released "2001: A Space Odyssey." The film has delighted and confounded audiences for 50 years now, and presaged many technological and cultural developments, from computers and AI to space exploration and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Computer scientist Stephen Wolfram, inventor of the computation software Mathematica and online Wolfram Alpha knowledge engine, spoke with Space.com about the impact the movie had on developing technologies of the day as well as where its predictions haven't come to fruition.

Space.com: Where does "2001" fit in the cannon of predictive science-fiction stories?

Stephen Wolfram: Oh, you know, it's a legend that everyone refers to. Probably more on the computer side than on the space side. By the mid-1960s, everybody was assuming that AI was just around the corner. [Brains, Minds, AI, God: Marvin Minsky Thought Like No One Else (Tribute)]

Space.com: What gave people this idea, given the state of computers in the late ꞌ60s?

Wolfram: Computers were a thing you read about, but not a thing you experienced. If people had been experiencing computers in the way that everyone experiences computers today, people would have had a much more realistic view.

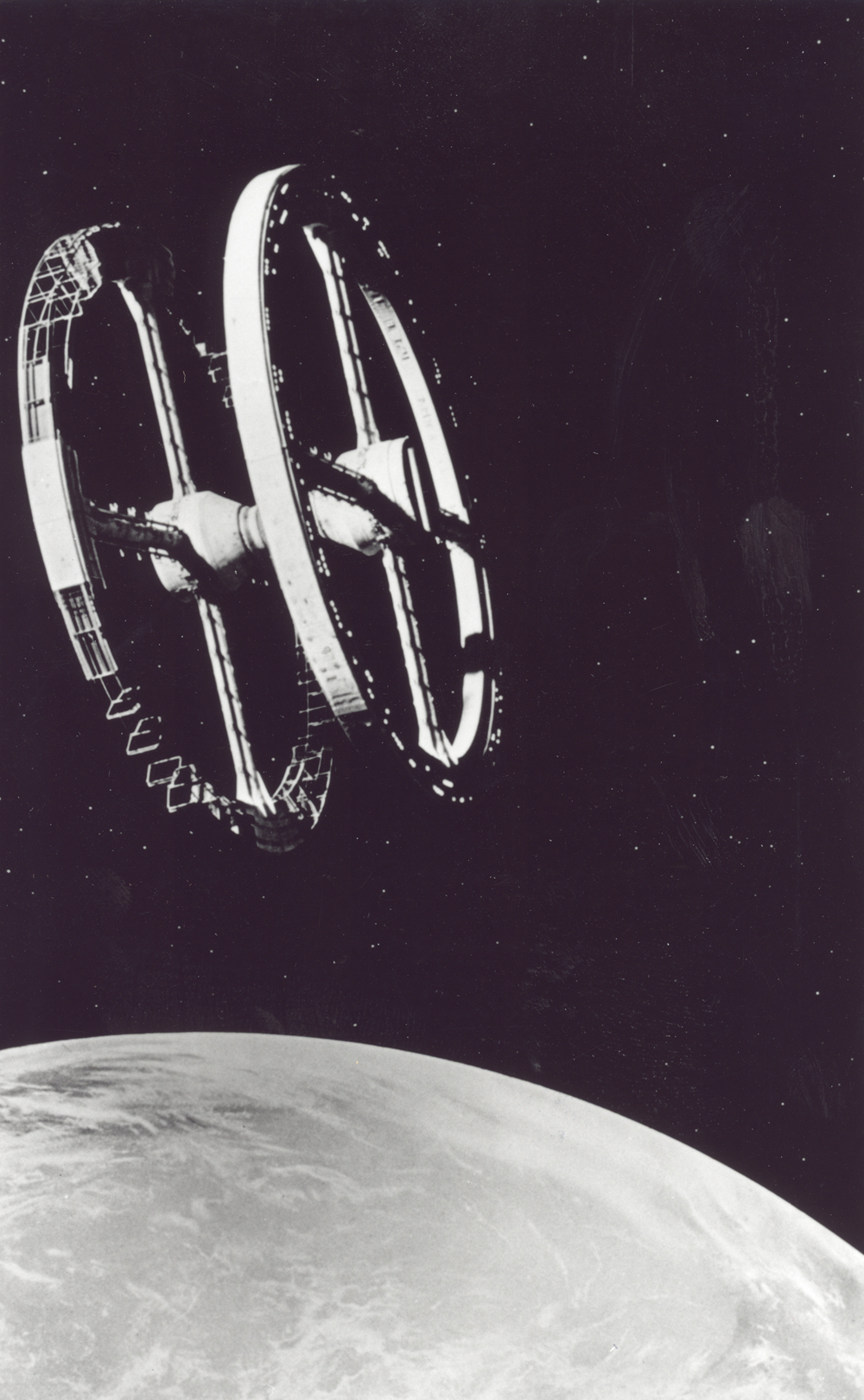

But people's knowledge of computers mostly came from science fiction and from the general media feeling about what was going on. And the general feeling was: machines have automated manual labor; machines will automate intellectual labor. It was just taken for granted, just as, at some level, I think it was taken for granted that by the time "2001" came along there'd be space stations and people would be able to go to Jupiter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

People had no idea what it meant to program a computer. For example, if you talked about bugs in computers, in software, even the professionals at that time would have looked at you kind of blankly. Like, "We don't know what you're talking about."

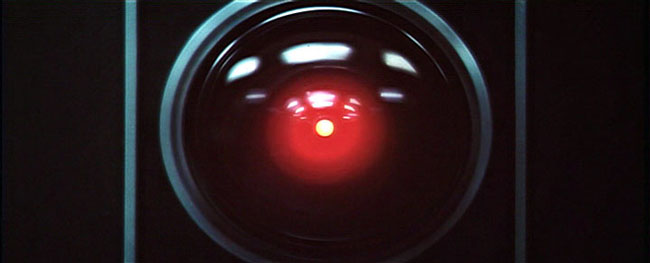

In the "2001" movie, HAL says that HAL is incapable of error, etcetera, etcetera. And that if there's a problem it's a human problem. And that was the view. The view was computers will be perfect and the humans will be sort of imprecise. The intuition that we have today about computers — software is buggy, something like that — that's an idea of probably the late ‘80s, early ‘90s. It didn't really exist before then to the general person.

Space.com: Do you think movies try to predict what will happen or portray what the creators hope will happen? And how does this play into how things actually develop?

Wolfram: I don't make movies, I've been a little bit involved in a few movies, but I think what tends to happen is people sort of say, "Let's do the best job we can seeing what this would be like."

Space.com: It sounds like technology feeds into the stories that are written, which in turn feeds back into what people care about and what they try to pursue.

Wolfram: Oh, sure. The fictional concept often ends up becoming a reality. Absolutely. It's hard to build it if you can't imagine it. If you start off imagining it in something like a movie, then that's a real good leg up on actually trying to build it. For quite a long time, HAL was the legendary version of what you were trying to build in AI. [From Reactive Robots to Sentient Machines: The 4 Types of AI]

I think that fiction is one of the channels through which ideas get put into a concrete enough form that people can relate to them. And particularly when the fiction is widely seen, like "2001" was, because then, when you talk about HAL, most techie people will have an idea of what you're talking about.

Space.com: How did "2001" affect the projects you've embarked on and the approach you took to them?

Wolfram: The notion of computers as visual things is probably something that I viscerally absorbed from "2001." Because at the time when "2001" came out, computers were absolutely not visual things. In the first computer I used, its only form of IO [input/ output] was a paper tape reader and punch and a tele-printer. So the concept of things on screens and flashing 3D things and so on was absolutely distant from the actual experience of computers.

Given that I've been involved in building a bunch of the technology that will lead us to HAL-like things, to what extent is fact following fiction, so to speak? I think the answer is I don't really know.

Space.com: Works of science fiction make many predictions. What differentiates the things that won't happen from those that haven't happened yet?

Wolfram: In the course of my life, for example, probably the thing that has most dramatically changed is computers. And what's perhaps interesting about that is there are many things that happened as a result that were not readily predictable.

There are details [in the movie] like the fact that they don't have the idea of multiple windows. So they put every different function in a different screen. That's something which isn't going to happen that way just because people figured out a better way to do it.

People at one time thought there would be cities in the deep ocean. That hasn't happened, and my guess is it won't happen. But it's not that there's something physically impossible about it; the main reason is because people don't care.

I think space in the last 50 years is an example of "it turned out we didn't care that much." And that's maybe turning around, again for very random reasons.

If you asked the question, "Is there something that is driving space exploration today?" the answer is: It's a bunch of people who grew up in a certain generation, who made enough money to waste some of it trying to build rockets. And I think it's great. [Smithsonian Channel Specials Tell Humanity's Story]

In the late ꞌ50s and early ꞌ60s, the driving thing was the Cold War and intercontinental ballistic missiles. That caused things to happen quite quickly at that time. After that, it was like "who cares?" Yes, it's kind of interesting science, but the typical person doesn't really care about exploring the moons of Jupiter. [Whereas] the typical person does care about going on their social network and doing social media for some number of hours per day.

Space.com: Given the differences between this wave of space enthusiasm and that of the Cold War, do you think we'll see things more like the space travel depicted in "2001"?

Wolfram: I think the answer is yes. When we'll see that, I don't know.

I don't know what will cause the everyday person to really experience space. Other than that they see cool pictures sent back from a spacecraft. I think that space today is definitely a spirit of adventure-type activity, as much as anything.

Insofar as space becomes a ubiquitous platform, things will emerge that we don't expect, and one of them, or several of them, may turn out to be really important.

Let me give you an example with computers. Nobody expected word processors.

In the 1960s, the concept that you would use computers to do word processing was absurd. Because, how did you use those computers? Well, they were expensive things, they cost millions of dollars each. They were used by specific operators; no ordinary person sat in front of the computer and did anything. You ran your job. It did a big computation and got results.

The idea you would waste the time of a computer, sitting, waiting for you to type a key and edit text was absurd. And the fact that word processing was the earliest large-scale application of computers was a weird, unexpected thing.

But that came out because computers had become a ubiquitous enough platform, and cheap enough, that you could do something as silly as word processing. The question is, if space becomes cheap enough that any old person can launch a payload into space, what will that then mean?

What is the analog of word processing for space?

This Q&A has been edited lightly for length and clarity. You can read a blog post by Wolfram on "2001" here.

Follow Harrison Tasoff @harrisontasoff. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harrison Tasoff is a science journalist originally from Los Angeles. He graduated from NYU’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program after earning his B.A. in mathematics at Swarthmore College. Harrison covers an array of subjects, but often finds himself drawn to physics, ecology, and earth science stories. In his spare time, he enjoys tidepooling, mineral collecting, and tending native plants.