This Space Junk Removal Experiment Will Harpoon & Net Debris in Orbit

The first experiment designed to demonstrate active space-debris removal in orbit has just reached the International Space Station aboard SpaceX's Dragon capsule.

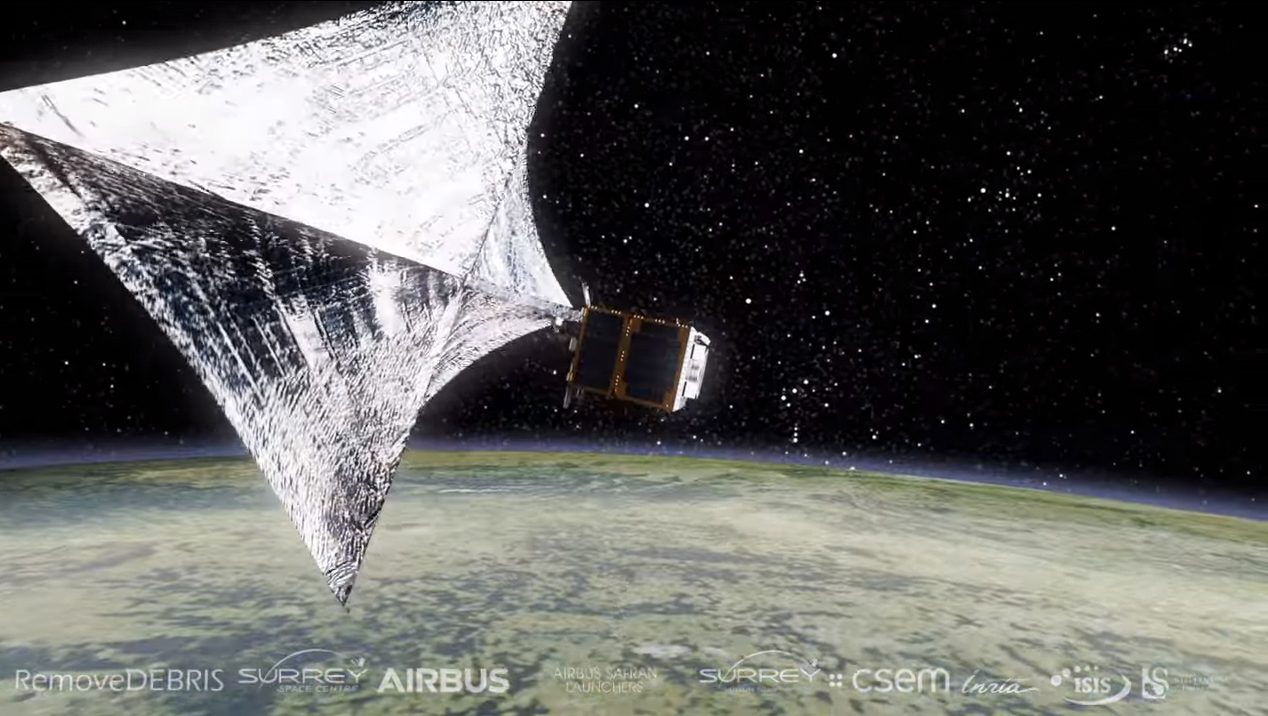

The RemoveDebris experiment, designed by a team led by the University of Surrey in the U.K. as part of a 15.2 million euro ($18.7 million), European Union (EU)-funded project, is about the size of a washing machine and weighs 100 kilograms (220 lbs.).

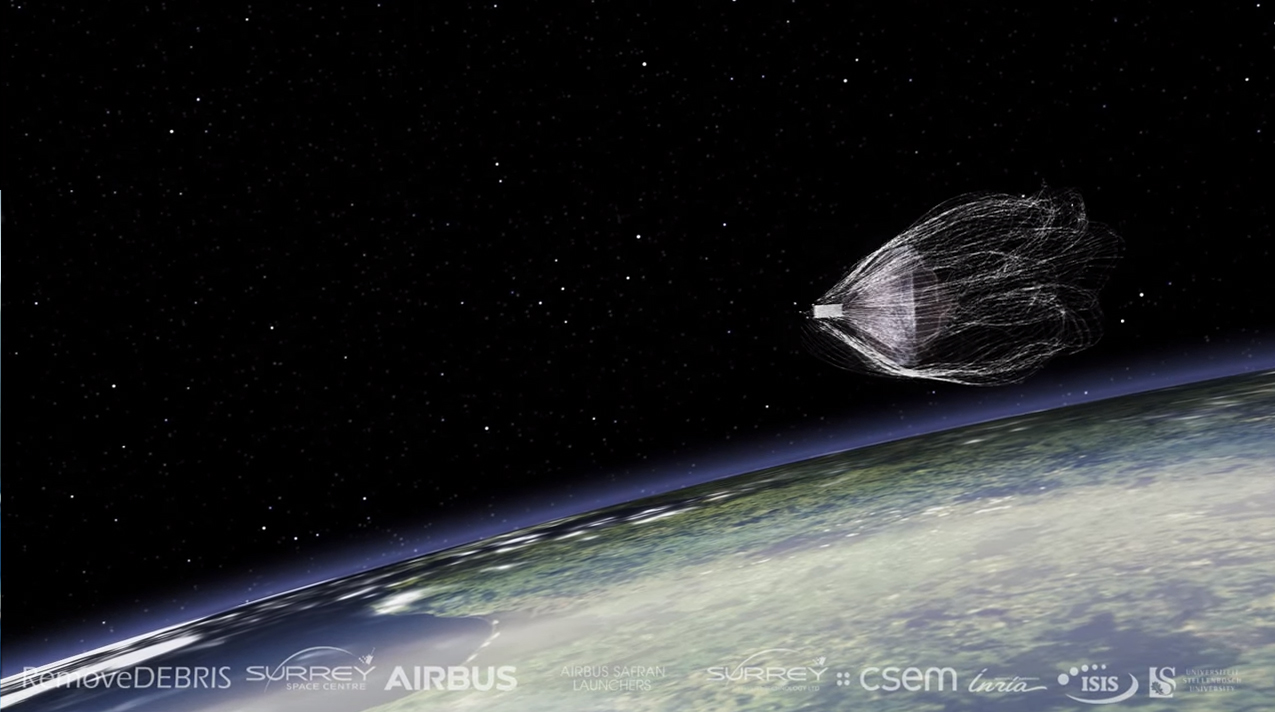

It carries three types of technologies for space-debris capture and active deorbiting — a harpoon, a net and a drag sail. It will also test a lidar system for optical navigation that will help future chaser spacecraft better aim at their targets. [7 Wild Ways to Clean Up Space Junk]

"For this mission, we are actually ejecting our own little cubesats," Jason Forshaw, RemoveDebris project manager at the University of Surrey, said last year. "These little cubesats are maybe the size of a shoebox, very small. We eject them and capture them with the net."

He said the team decided to carry up their own pieces of space junk, due to legal issues that don't allow the manipulation of space objects that belong to someone else, even if the objects are no longer functional.

The main spacecraft will be launched later this year from the International Space Station using the commercial cubesat deployer operated by Houston, Texas-based NanoRacks. Once the spacecraft reaches a safe distance from the space station, it will eject the two cubesats. After that, the chaser spacecraft will deploy the net, aiming to capture the cubesats.

Forshaw said that for the purpose of this experiment, the chaser spacecraft won't be connected to the net with a tether, as it would be in a real mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There [are] a lot of problems that could occur with a tether," he said. "For example, the cubesat could bounce back and hit your main satellite."

The space junk harpoon, built by Airbus Defence and Space in the U.K., will be later fired into a fixed target that will be extended from the main satellite on a boom.

After it completes the harpoon, net and lidar experiments, the RemoveDebris spacecraft will deploy the drag sail that will speed up its deorbiting process.

"We are testing these four technologies in this demonstration mission, and we want to see whether they work or not," said Forshaw, referring to the harpoon, net, drag sail and lidar. "If they work, then that would be fantastic, and then these technologies could be used on future missions."

The cubesats captured in the net will deorbit naturally within a few months, Forshaw said.

"The absolute maximum for which it stays up there would be one year," he said. "These things at low altitudes do come down very quickly. We are not going to contribute to any further space debris."

"It is important to remember that a few significant collisions have already happened," Professor Guglielmo Aglietti, director of the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey, said in the statement. "Therefore, to maintain the safety of current and future space assets, the issue of the control and reduction of the space debris has to be addressed. "

International guidelines exist for satellite operators to ensure their spacecraft are removed within a reasonable amount of time after a mission ends. However, experts agree that without active removal technologies, the space around Earth might become unstable. The world's space agencies estimate that five large, defunct satellites need to be removed from low Earth orbit every year to help prevent the Kessler syndrome — the unstoppable cascade of orbital collisions predicted by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in the late 1970s.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.