Could Isaac Asimov's Planet Where Nightfall Almost Never Comes Really Exist?

The classic science-fiction tale "Nightfall" is set on a planet where night only falls every 2,049 years. Now, a scientist proposes a planet could exist on which night would never fall — provided it was lit on all sides by a ring of stars orbiting a black hole.

In "Nightfall," science-fiction grandmaster Isaac Asimov imagined the potential consequences of nightfall on the planet Kalgash, which experienced permanent daytime except for once every two millennia or so. Kalgash is said to orbit a yellow dwarf star like the sun, while five other stars exist nearby, and the entire system lies within a cluster of tightly packed stars, such as one of the 150 or so known globular clusters orbiting the Milky Way galaxy.

The inspiration for "Nightfall" came from a conversation Asimov had with John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine, regarding a quotation from the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson: "If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore, and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God!" According to Asimov's autobiography, Campbell's opinion to the contrary was, "I think men would go mad." [Best Science Fiction Books for Space Fans]

Sean Raymond, an astrophysicist at the Observatory of Bordeaux in France, read "Nightfall" "when I was in college and loved the story," he said. "When I started questioning the scientific validity of different sci-fi settings, 'Nightfall' came to mind."

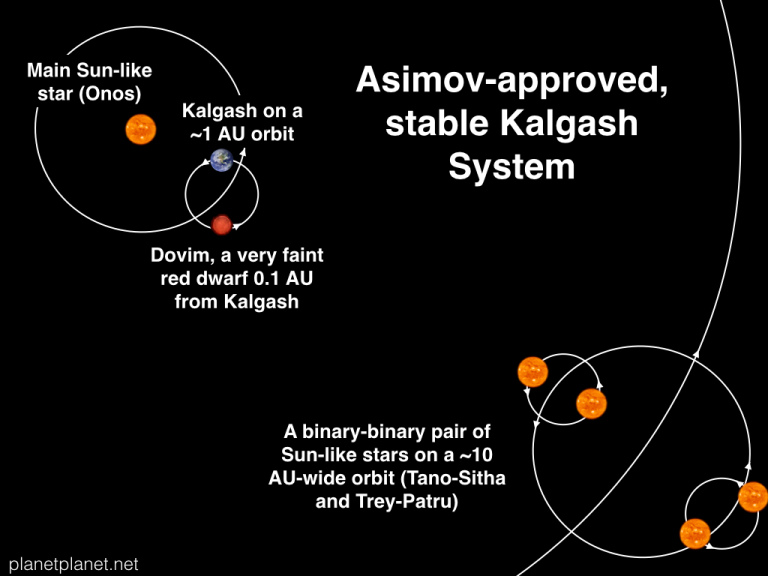

When Raymond calculated Kalgash's behavior as described in "Nightfall," he found that its longest stretch of daytime was only two months long, not 2,049 years. Still, Raymond said Asimov remained one of his heroes, so as part of a column Raymond writes, "Real-Life Sci-Fi Worlds," he set out to see if a planet that experienced permanent daytime was possible.

"My research is based on understanding how planetary systems form and evolve — I run simulations to try to understand the solar system's origins and also what processes shape extra-solar planetary systems," Raymond told Space.com. "One way to address problems in the field is to ask 'what if' types of questions."

At any given time, a single planet orbiting a single star can have more than half of its surface illuminated. For example, when it comes to Earth, not only is the side that directly faces the sun lit, but twilight can keep Earth's sky bright until the sun is about 15 degrees below the horizon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Raymond then sought out to illuminate the side of a planet facing away from its central star. That requires at least one ring of stars. [The Strangest Alien Planets We've Found So Far]

Raymond calculated that a ring of sun-like stars could be stable if there are at least seven stars in the ring, they all have the same mass, they are all evenly spaced along the same orbit, and they orbit something a lot more massive — in the case of a ring of seven sun-like stars, a black hole at least 1,000 times the sun's mass.

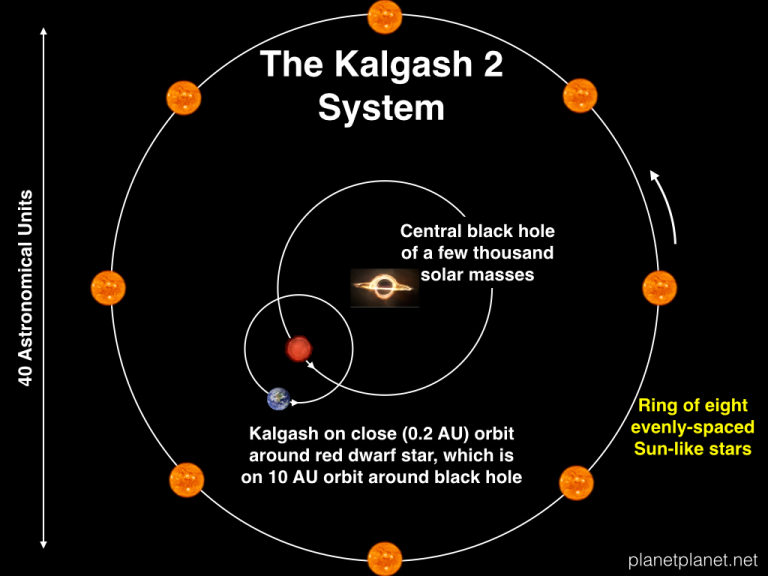

One version of Kalgash that Raymond modeled, dubbed Kalgash 2, had a black hole a few thousand times the sun's mass with eight sun-like stars in a ring around it 40 astronomical units (AU) wide, an AU being the average distance between Earth and the sun, about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). Halfway between this ring and the black hole is a red dwarf star half the sun's mass, around which an Earth-like planet orbits at just 0.2 AU. The planet is tidally locked, meaning one side constantly faces its star, and its backside is constantly lit by the ring of sun-like stars.

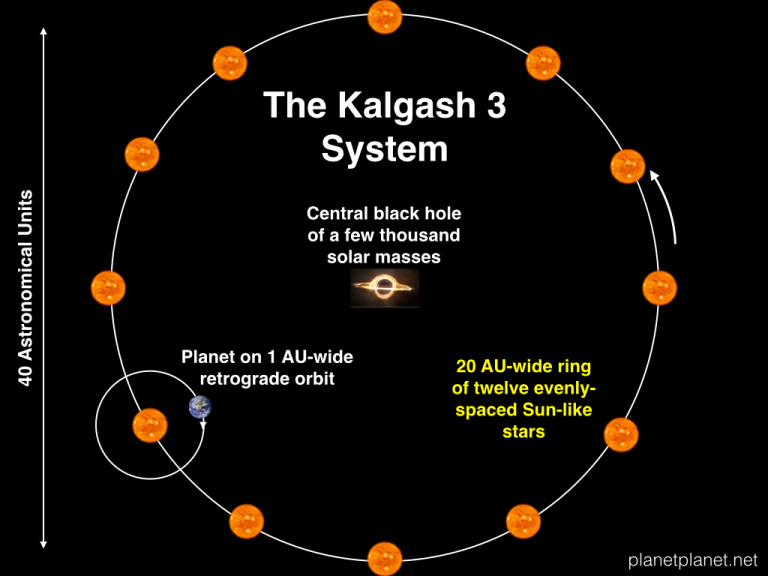

Another scenario, dubbed Kalgash 3, imagined a ring of a dozen sun-like stars 40 AU wide orbiting a black hole a few thousand solar masses in size. An Earth-like planet orbiting one of these 12 stars could also experience permanent daylight.

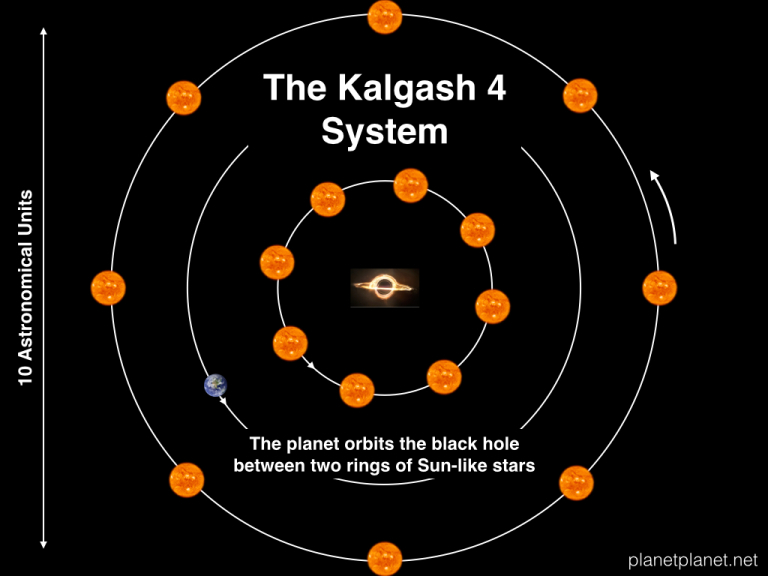

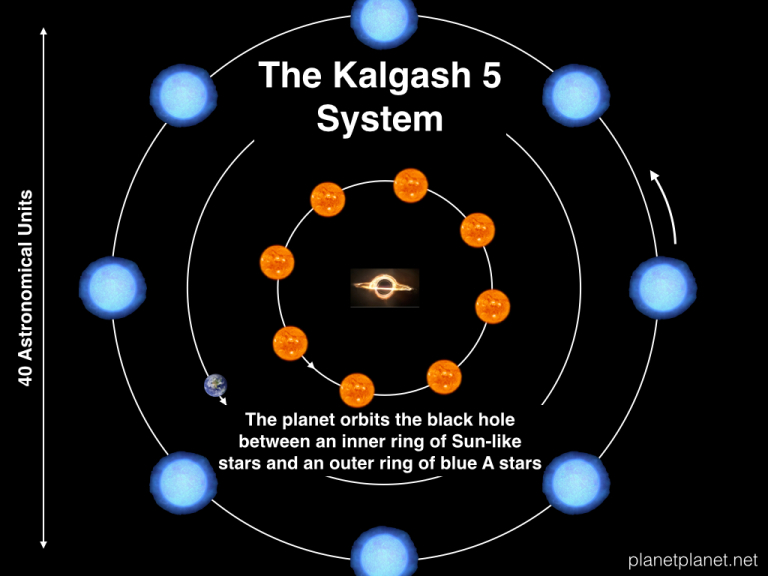

With Kalgash 4, Raymond imagined an Earth-like planet orbiting a black hole in between two rings of sun-like stars, with an inner ring of eight sun-like stars 2 AU wide, and an outer ring of eight sun-like stars 20 AU wide. The last scenario, Kalgash 5, also modeled an Earth-like planet orbiting a black hole in between two rings of stars, except in that version, the outer ring was 40 AU wide and consisted of eight bright blue stars, giving the planet's sky a gradient of color throughout the day.

However, in most of these variations, it was challenging to imagine how darkness could only rarely fall, Raymond said. In the case of multiple rings of stars, it was difficult to see darkness ever falling, while in the case of a single ring of stars, giving the planet a large moon would make it possible for darkness to fall, but frequently, not rarely, he said.

One possibility leading to very rare darkness would involve giving the planet of Kalgash 2 two large moons, Raymond said. Each moon would occasionally eclipse one of the stars in the outer ring, but only extremely rarely would both moons simultaneously eclipse two of the closest outer stars.

All in all, Raymond feels exercises such as writing about the science of science fiction "makes me better at science. Giving myself permission to 'go there' — coming up with ideas that end up quite far from reality — ends up being a strength. Many researchers have trouble allowing their minds to stray too far into the different, into what seems ridiculous, but that is where the seeds of new, not-ridiculous ideas often come from."

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us