Oceans' Mysterious Magnetic Field Is Mapped in Stunning Detail from Space

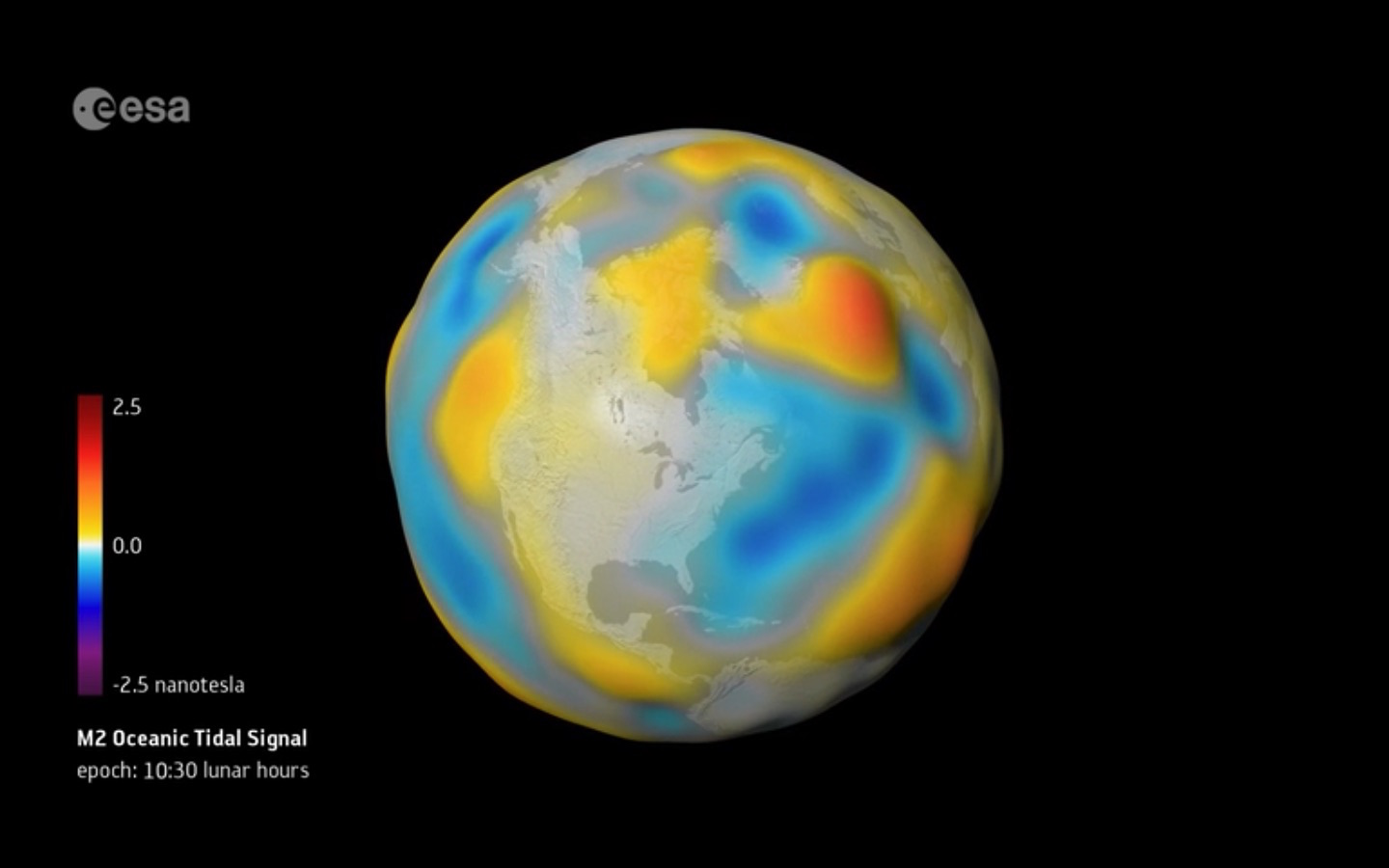

Satellites circling Earth have mapped an elusive, invisible force in unprecedented detail: the magnetic field created by the currents in the planet's salty oceans, according to new research.

Most people are familiar with the powerful magnetic field produced by Earth's molten iron core, but less is known about the field generated by its oceans.

To learn more, the European Space Agency (ESA) directed three identical spacecraft, which the agency launched in 2013 and collectively calls Swarm, to map the mysterious magnetic field emanating from the oceans' tides. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

The new research, as well as the digital 3D map it helped create, is providing new insight into how the protective, cocoon-like magnetic shield is generated, as well as how it behaves and changes over time.

The magnetic field — that is produced by the oceans, the molten core and rocks in the crust and upper mantle — protects the planet from streams of charged particles known as the solar wind. If these charged particles weren't deflected by the magnetic field, they could jumble the navigation of satellites and aircraft and even interfere with electrical power grids, University of Leeds geophysicists Phil Livermore and Jon Mound wrote in an article for The Conversation. Not to mention, the radiation could wreak havoc on human health.

To get a better handle on the forces contributing to this field, the researchers had Swarm map the oceans' contributions to it with remarkable precision.

The researchers chose to focus on the oceans because they make a tiny, but important contribution to the Earth's overall magnetic field. The salt within seawater can conduct electricity. And oceans don't remain still; rather, they move in cycles, up and down. As the tides cycle through the world's oceans, that salty water essentially tugs on the magnetic field above our planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have used Swarm to measure the magnetic signals of tides from the ocean surface to the seabed, which gives us a truly global picture of how the ocean flows at all depths — and this is new," Nils Olsen, the head of geomagnetism at the Technical University of Denmark, said in a statement.

The magnetic field generated by the oceans is quite small. "It's about 2 [to] 2.5 nanotesla at satellite altitude, which is about 20,000 times weaker than the Earth's global magnetic field," Olsen told BBC News.

The newly analyzed data will give researchers a more nuanced view of how the oceans are affected by climate change, Olsen noted. "Since oceans absorb heat from the air, tracking how this heat is being distributed and stored, particularly at depth, is important for understanding our changing climate," Olsen said in the statement.

Moreover, the tidal magnetic signal, in turn, induces a weak magnetic response from deep under the seabed, he said.

The research is the latest discovery Swarm has gathered with respect to Earth's magnetic field. Last year, researchers announced that the spacecraft had helped map magnetic signals emitted by Earth's outer shell, known as the lithosphere, Live Science previously reported.

The new research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented yesterday (April 10) at the 2018 European Geosciences Union meeting in Vienna.

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Laura is an editor at Live Science. She edits Life's Little Mysteries and reports on general science, including archaeology and animals. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and an advanced certificate in science writing from NYU.