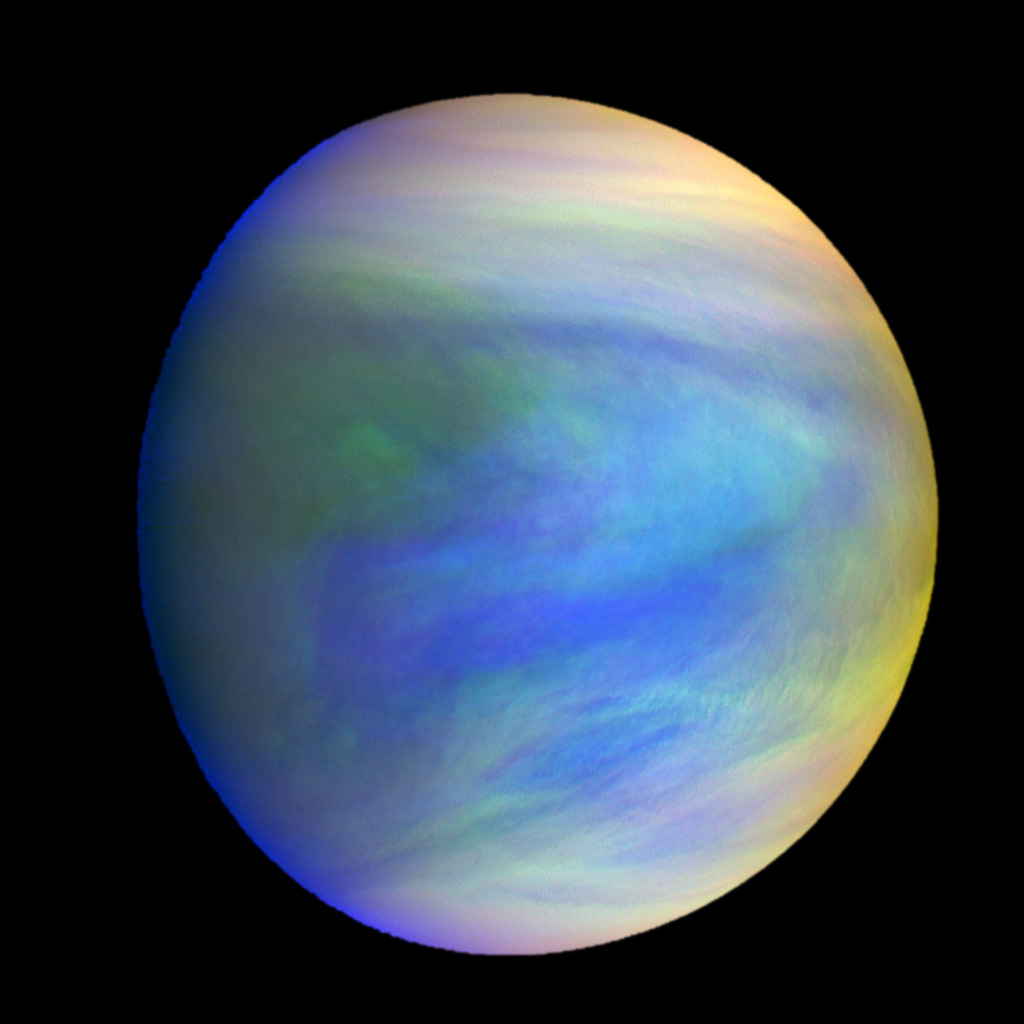

STANFORD, Calif. — Venus shouldn't be dismissed as a possible abode for life, some scientists stress.

Sure, the planet's surface is famously inhospitable today — bone-dry and hot enough to melt lead, with an atmospheric pressure 90 times greater than that of Earth at sea level. To feel that same amount of squeeze on our planet, you'd have to descend about 3,000 feet (900 meters) into the oceans.

But Venus was a temperate world long ago, with seas that persisted for eons — perhaps 2 billion years or more, according to recent modeling research. [Photos of Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

Venus may therefore have been a habitable planet "for much of solar system history," astrobiologist David Grinspoon, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, said Thursday (April 12) during a talk at the Breakthrough Discuss conference here at Stanford University.

And Earth's so-called sister planet could potentially support life to this day, at least in places. Though Venus' surface has gone hellish hothouse, the environment a few dozen miles high in the skies is pretty benign, Grinspoon and others have stressed. Temperatures and pressures up there are close to those of Earth's surface, so it's possible that Venusian life — if it ever existed — didn't die out with the dramatic climate shift long ago but rather retreated into the clouds.

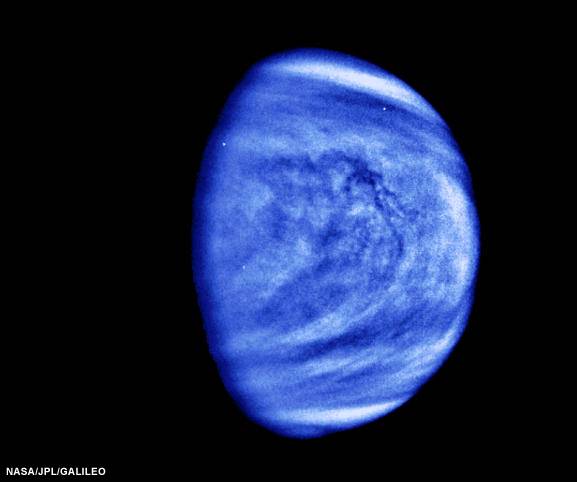

Those clouds are made mostly of sulfuric acid, which would seem to argue against the Venus-life idea. But over the last few decades, biologists have found all manner of hardy microbes here on Earth capable of tolerating similarly extreme conditions. And these same acidic Venus clouds could potentially provide chemical energy to any microbes that may be floating around up there, researchers have said.

Intriguingly, Venus' upper atmosphere also abounds with a mysterious compound that absorbs ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the high-energy light that causes sunburns here on Earth. Nobody knows what this stuff is or where it comes from, but some scientists have speculated that it could be a biological pigment — perhaps a sulfur-based sunblock of some sort.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And life didn't necessarily have to arise on Venus to thrive there, Grinspoon added: The planet has gobbled up many tons of Earth rocks that were blasted into space by violent impacts over the past 4.5 billion years, some of which may have sheltered unwittingly voyaging microbes. (Venus material has also made its way to Earth, so it's also possible that our planet was colonized long ago by native Venusians.)

Grinspoon isn't claiming that life exists on Venus, just that it's a possibility scientists should consider more seriously. And some of his colleagues agree.

For example, during a separate panel discussion here Thursday, the participating scientists were asked which solar system body they would visit first to search for alien life. Mars, the Jupiter moon Europa and the Saturn satellites Titan and Enceladus all got votes. But one of the Europa proponents — Cynthia Phillips, a planetary geologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California — also gave a shout-out to the second rock from the sun.

"I think we should really take another look at Venus," Phillips said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook orGoogle+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.