15 Space Travel Tips from an Astronaut

An Astronaut's Video Guide to Life in Space

For wannabe astronauts and space tourists, Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield offers a lengthy video guide that goes over the intricacies of spaceflight. In more than 9 hours of content, Hadfield's MasterClass series covers everything from basic orbital mechanics and rocketry, to how to train as an astronaut, to what the future holds for space exploration.

"This class is for anyone who's interested in exploration, and not just exploring space," Hadfield says in the video series. "That's the obvious core, being an astronaut, but you learn a lot of things along the way." He adds that, as an astronaut, you learn "how to turn yourself into somebody different than you used to be" through diligent practice, observation and thinking about how to mitigate problems.

Here are some of his key spaceflight tips.

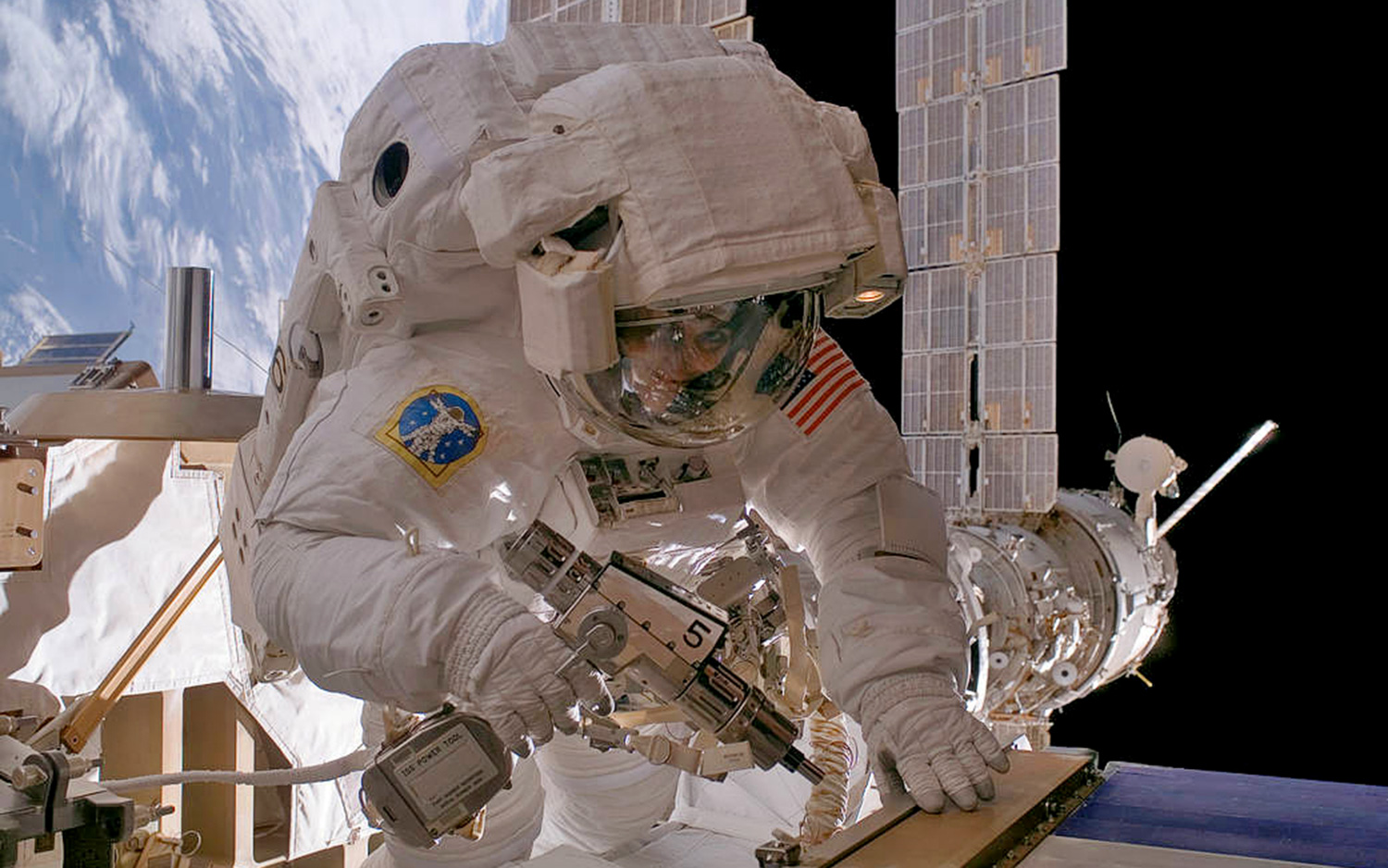

In this photo: Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield flew three times in space and commanded the International Space Station during Expedition 35 in 2013.

Start astronaut life as an expert, and become a generalist.

Astronauts need to manage danger and do delicate tasks at the same time.

Hadfield's final mission in space was his longest — five months on the space station, including commanding the orbiting complex during Expedition 35 in 2013. But no matter how long the mission, astronauts must always be aware of the danger and be able to work effectively through it.

Astronauts always need to be ready to spring into action if an emergency happens. On the other hand, an astronaut must also fully focus on the experiment at hand, which could represent a scientist's lifework. So while working under demanding conditions, every astronaut also must take responsibility for the experiment that people on the ground are hoping will go well.

"You just have to recognize that this is worth doing; exploring the rest of the universe is worth taking a risk for," Hadfield said, adding that the key is to "get ready for the things that would otherwise normally unnerve you, or make you afraid or nervous. Astronauts overcome fear through constant practice.

In this photo: Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield holds a radiation experiment made up of bubble detectors during Expedition 34 in 2013.

Survival training will forge the right astronaut team.

Hadfield went into space three times with astronauts from all over the world. He said he always tried to behave in the Astronaut Office as though anybody there would be on his crew. This meant trying to predict the best way he could behave to improve interpersonal relations, no matter what the other person's personality.

Astronauts are also required to undergo survival training and use the time to not only figure out how to survive in extreme conditions but also practice leadership techniques with prospective crewmates.

For example, Hadfield recalled a rural Utah expedition in which one crewmember practiced "silent leadership," meaning they commanded the others without saying anything. (For example, that leader could have used gestures such as pointing to accomplish a task.) This situation could happen in spaceflight if crewmembers were in a situation in which they couldn't hear one another. Hadfield said the practice was valuable under a relatively safe set of circumstances on the ground. [What It's Like to Become a NASA Astronaut: 10 Surprising Facts]

In this photo: In 2013, then-NASA astronaut candidates Anne McClain (left) and Josh Cassada build survival gear during a three-day wilderness session.

The moment of launch feels totally unreal.

Hadfield spent three years preparing for launch day as an astronaut, and 26 years from the time he decided to be an astronaut, at age 9. He spent most of his life practicing and preparing for the moment when he would take his seat on a space shuttle, which was the world's first reusable spacecraft and carried astronauts to space from 1981 to 2011. He described his first launch day in 1995 as an unreal experience.

"You're in the final stages of doing something very demanding, but you try to be as ready for it as any human being can be," he said. "It's pretty amazing to come around that corner at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida," he added, saying the view of "your spaceship" was a magnificent sight.

"You don't actually believe you are leaving Earth today," Hadfield said, adding that the reality grew clearer as the crew completed the normal prelaunch checks and everything appeared fine. When Atlantis finally lifted off, he said, the noise and vibration made him feel like a leaf in a hurricane. "You are puny compared to what is going to happen," he added.

In this photo: The April 2001 launch of space shuttle Atlantis during mission STS-100 to the International Space Station. Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield was one of the crewmembers.

Use the right tool for the job.

Astronauts can only carry so much into space with them, which means they have to know how to improvise. (3D printing is now available on the space station to help with that issue, but the tool may not necessarily be ready if the need is urgent.) Hadfield encountered that need himself during his first spaceflight, in 1995, during STS-74. His crew had docked with the Russian Mir space station, and it was Hadfield's job to open the hatch.

"Some very strong and well-meaning technician from Russia had decided that his part of the station was going to be secure, and he had strapped down that hatch and put a webbing across it, and wire tires. It was almost impenetrable to get through this hatch," Hadfield recalled.

With few tools available in the space shuttle and the clock ticking away, Hadfield improvised with a jackknife and successfully sawed the webbing away. "I felt like I was breaking into the Russian space station all by myself," he joked. "The moral of the story is, when you're going into somebody else's spaceship, bring a jackknife."

In this photo: NASA astronaut Sunita Williams uses a pistol grip tool during a spacewalk on Expedition 14 in 2007.

Visualize how Earth looks when you get ready for a spacewalk.

Astronauts spend hundreds of hours practicing spacewalks at the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory near Johnson Space Center in Houston. It's a huge pool that holds 6.2 million gallons (23.5 million liters) of water. While the crew is surrounded by safety divers, Hadfield said he tried to keep the simulation as high-fidelity as possible. He urged the astronauts around him to use correct radio protocols and to otherwise behave as though they were far from help, working on the space station.

One thing he practiced repeatedly was the overwhelming view he would face upon opening the hatch for the first time. By pretending Earth was in front of him when he opened the hatch, he felt better prepared during his first spacewalk, in 2001. "It's as if the next time you come out of the bathroom … you are standing on the top of Mount Everest," he said of the view of our planet, upon leaving the space station. "It's that sort of weirdness of juxtaposition of one place to another," he added.

In this photo: NASA astronaut Clay Anderson on a July 2007 spacewalk during Expedition 15.

One-pagers will get you through.

Astronauts need to be learning machines, mastering everything from how to fix the ISS toilet to how to capture a visiting spacecraft using the robotic Canadarm2. Procedures and safety protocols for each system can easily fill textbooks. Hadfield's solution? He created a manual for his STS-100 shuttle mission full of one-pagers, such as one for how to operate the pistol grip tool during a spacewalk.

Hadfield created his short guides by envisioning how he — the operator of a specific system — would turn dials, view displays or otherwise complete the functions of that system. And he would remember to write everything with a goal in mind, such as how to dock with a space station. This method came in handy during the approach to the Russian space station Mir, he recalled, when two sensors on the shuttle showed different distances to the hatch. Hadfield had a one-pager for manual dockings on hand, and with that procedure, the crew arrived safely. [Astronaut Chris Hadfield's Guide to Writing 'An Astronaut's Guide to Life on Earth]

In this photo: Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield shows a training manual for STS-100, his space shuttle mission in 2001. This included several one-pagers for tools, procedures and other vital spaceflight information.

Astronauts mourn lost crewmates but realize fear is a choice.

Hadfield was close to Rick Husband, the commander of Columbia space shuttle mission STS-107. Columbia broke up during re-entry due to a breach in the shuttle's protective tiles on its belly, killing all seven astronauts on board. Hadfield and Husband were test pilots together and shared many interests; Hadfield said he expected they would have been friends through the rest of a natural human life span.

Hadfield, along with the rest of his colleagues and friends, deeply mourned the loss of Husband and all of the other astronauts on STS-107. But, Hadfield said, "what really matters — of course, in life — is what do you choose to do next." Hadfield imagined what would have happened if he had died and Husband remained alive. "It never occurred to me for a second that I would expect Rick would quit — or to say, 'Wow, I never knew there was danger with this job and someone's been killed. I need to run away.' That would be ridiculous," Hadfield said.

So Hadfield remained an astronaut. He added that all pilots are familiar with "boldface" sections in their manuals — the sections that are critical to safety. "That section of the book is written in blood," Hadfield said. He, along with all of his colleagues, tried to remember the "boldface" added to the manuals after Columbia to improve safety on future spaceflights.

In this photo: The STS-107 shuttle crew that died during shuttle Columbia's re-entry in February 2003. Bottom row, left to right: Kalpana Chawla, Rick Husband, Laurel Clark, Ilan Ramon. Top row, left to right: David Brown, William McCool, Michael Anderson. All of the astronauts were from NASA except Ramon, who represented Israel.

There's a reason they put astronauts in Mission Control.

There are at least four "mission controls" that space station astronauts talk to, Hadfield said. Along with the most famous one in Houston, there are mission control centers near Moscow, near Munich and near Montreal. But it was the Houston Mission Control with which Hadfield was most familiar. He served as a "capsule communicator," or "capcom," for 25 space shuttle missions and was also NASA's chief capcom for a while.

Traditionally, the capcom is an astronaut, and Hadfield said that is a necessary item for astronauts in space. When people are away from home for months at a time, he said, they become so focused on the mission that they need to put away thoughts of home and family much of the time.

So the astronaut capcom on the ground acts as a trusted colleague to consider Earth's priorities. This "trusted agent," as Hadfield called the capcom, makes decisions that the capcom knows will benefit the crew, because the capcom is an astronaut, too. "We don't have to question it, [and] we don't have to argue about it; this is a person we trust in Mission Control," Hadfield said.

In this photo: Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield (center) worked as a capcom during space shuttle mission STS-106 in September 2000.

Every space machine has a design trade-off.

There can never be a perfect machine in space; every design has a trade-off. There will always be something designers have to give up, whether it be fuel efficiency, time, performance, safety or some other metric.

Hadfield used the space shuttle as an example. The shuttle had wings and a large payload bay, which allowed it to bring satellites into space and return them home. It also could carry large facilities such as Spacelab, a reusable scientific laboratory. But the design also complicated re-entry — so much so that astronauts preferred to use a computer rather than fly in manually.

Today, the next generation of spacecraft are a bit of a throwback to the 1960s and 1970s capsules NASA used, Hadfield said. Although the Boeing Starliner and the SpaceX Dragon commercial crew vehicles have more advanced electronics than their predecessors, their shape resembles the gumdrops of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs. It appears that sending the crew and cargo separately into space might be the best way to go, Hadfield said.

In this photo: Chris Hadfield with a mock rocket.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.