'White Holes' May Be the Secret Ingredient in Mysterious Dark Matter

White holes, which are theoretically the exact opposites of black holes, could constitute a major portion of the mysterious dark matter that's thought to make up most of the matter in the universe, a new study finds. And some of these bizarre white holes may even predate the Big Bang, the researchers said.

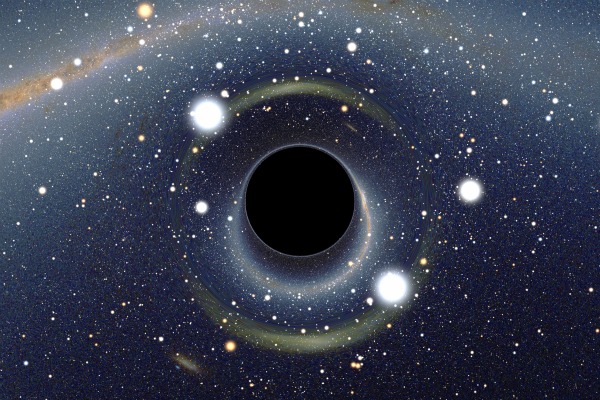

Black holes possess gravitational pulls so powerful that not even light, the fastest thing in the universe, can escape them. The invisible spherical boundary surrounding the core of a black hole that marks its point of no return is known as its event horizon. [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

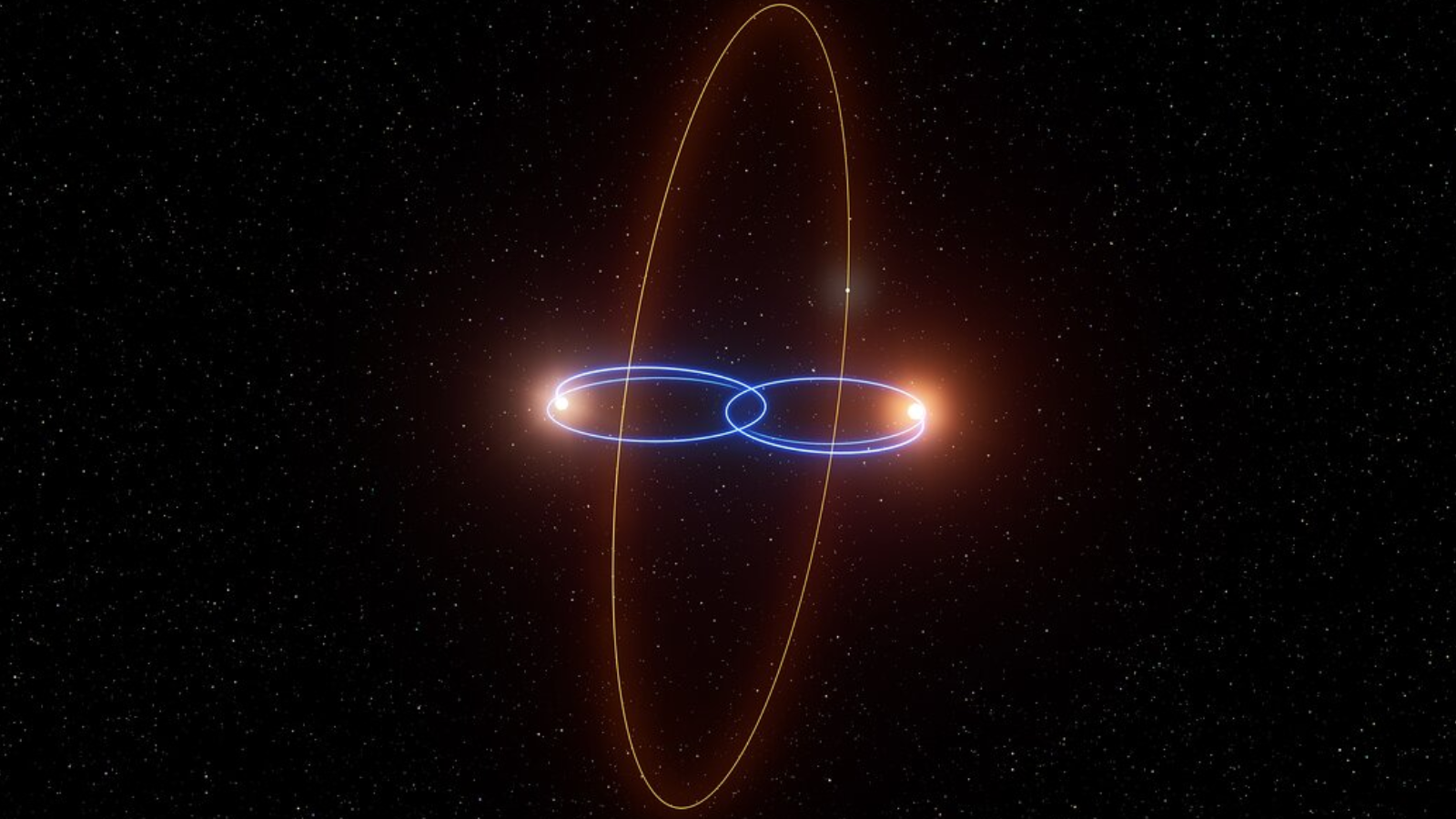

A black hole is one prediction of Einstein's theory of general relativity. Another is known as a white hole, which is like a black hole in reverse: Whereas nothing can escape from a black hole's event horizon, nothing can enter a white hole's event horizon.

Previous research has suggested that black holes and white holes are connected, with matter and energy falling into a black hole potentially emerging from a white hole either somewhere else in the cosmos or in another universe entirely. In 2014, Carlo Rovelli, a theoretical physicist at Aix-Marseille University in France, and his colleagues suggested that black holes and white holes might be connected in another way: When black holes die, they could become white holes.

In the 1970s, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking calculated that all black holes should evaporate mass by emitting radiation. Black holes that lose more mass than they gain are expected to shrink and ultimately vanish.

However, Rovelli and his colleagues suggested that shrinking black holes could not disappear if the fabric of space and time were quantum — that is, made of indivisible quantities known as quanta. Space-time is quantum in research that seeks to unite general relativity, which can explain the nature of gravity, with quantum mechanics, which can describe the behavior of all the known particles, into a single theory that can explain all the forces of the universe.

In the 2014 study, Rovelli and his team suggested that, once a black hole evaporated to a degree where it could not shrink any further because space-time could not be squeezed into anything smaller, the dying black hole would then rebound to form a white hole.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We stumbled onto the fact that a black hole becomes a white hole at the end of its evaporation," Rovelli told Space.com.

Black holes nowadays are thought to form when massive stars die in giant explosions known as supernovas, which compress their corpses into the infinitely dense points known as singularities at the hearts of black holes. Rovelli and his colleagues previously estimated that it would take a black hole with a mass equal to that of the sun about a quadrillion times the current age of the universe to convert into a white hole. [Supernova Photos: Great Images of Star Explosions]

However, prior work in the 1960s and 1970s suggested that black holes also could have originated within a second after the Big Bang, due to random fluctuations of density in the hot, rapidly expanding newborn universe. Areas where these fluctuations concentrated matter together could have collapsed to form black holes. These so-called primordial black holes would be much smaller than stellar-mass black holes, and could have died to form white holes within the lifetime of the universe, Rovelli and his colleagues noted.

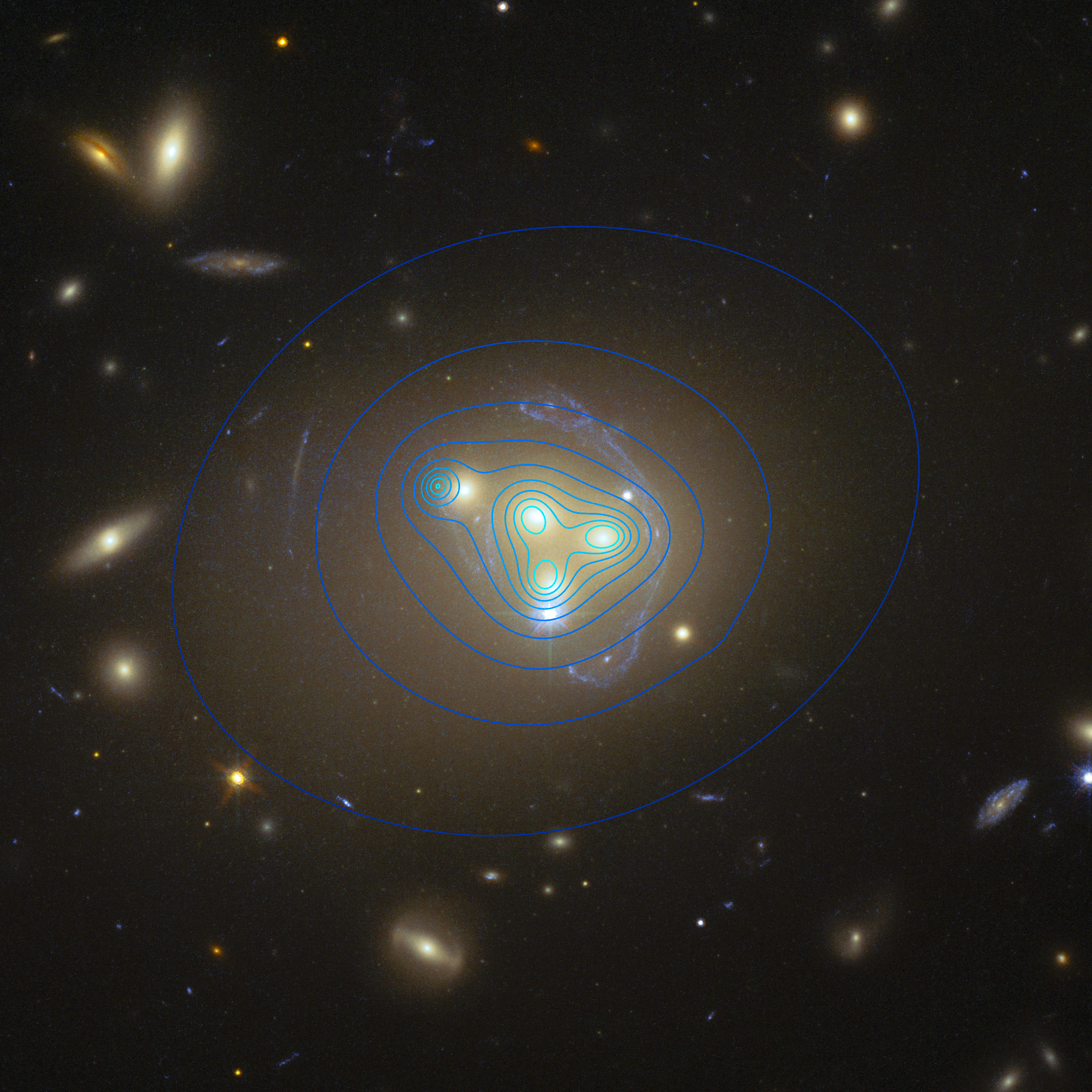

Even white holes with microscopic diameters could still be quite massive, just as black holes smaller than a sand grain can weigh more than the moon. Now, Rovelli and study co-author Francesca Vidotto, of the University of the Basque Country in Spain, suggest that these microscopic white holes could make up dark matter.

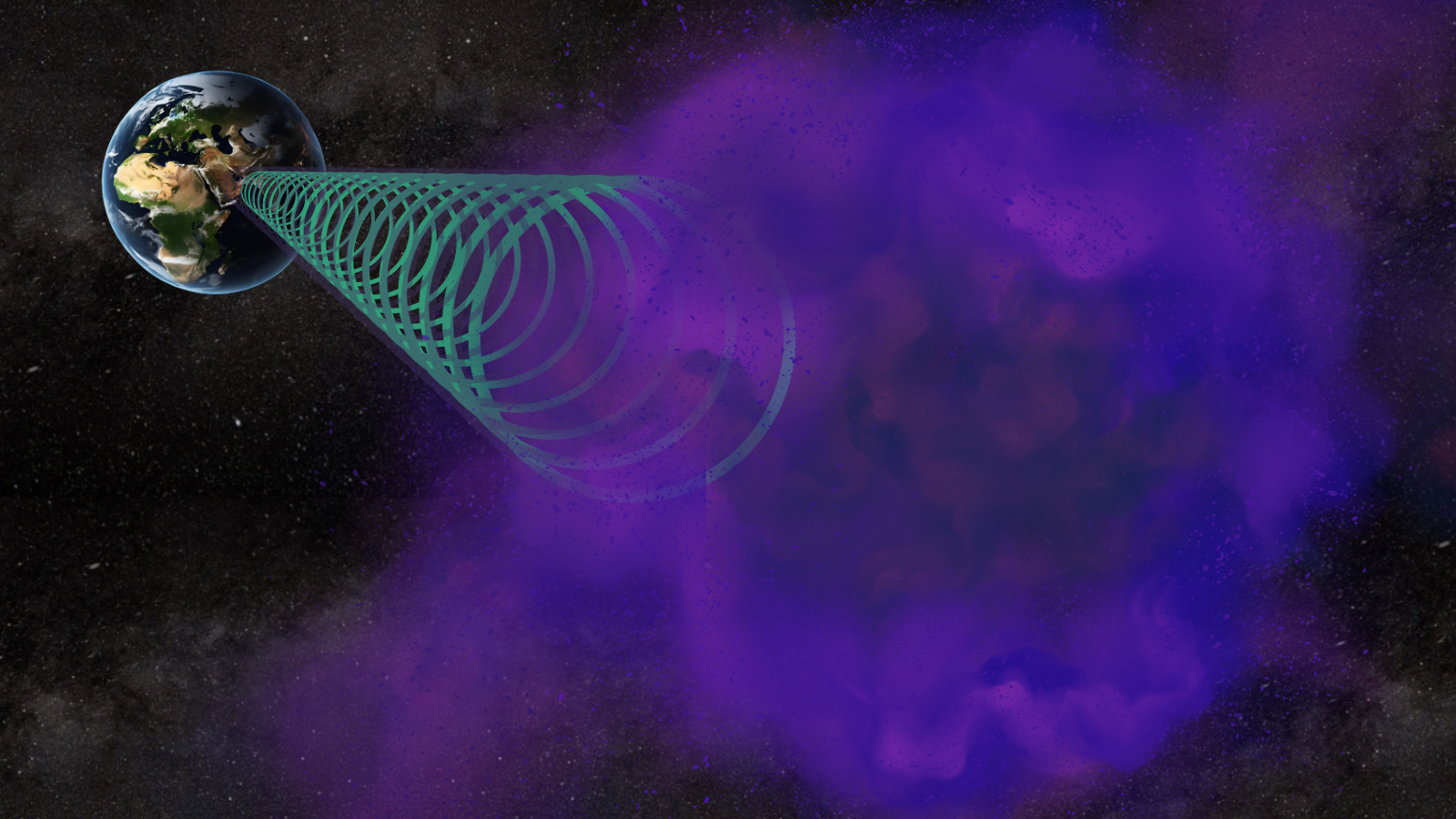

Although dark matter is thought to make up five-sixths of all matter in the universe, scientists do not know what it's made of. As its name suggests, dark matter is invisible; it does not emit, reflect or even block light. As a result, dark matter can currently be tracked only through its gravitational effects on normal matter, such as that making up stars and galaxies. The nature of dark matter is currently one of the greatest mysteries in science.

The local density of dark matter, as suggested by the motion of stars near the sun, is about 1 percent the mass of the sun per cubic parsec, which is about 34.7 cubic light-years. To account for this density with white holes, the scientists calculated that one tiny white hole — much smaller than a proton and about a millionth of a gram, which is equal to about the mass of "half an inch of a human hair," Rovelli said — is needed per 2,400 cubic miles (10,000 cubic kilometers).

These white holes would not emit any radiation, and because they are far smaller than a wavelength of light, they would be invisible. If a proton did happen to impact one of these white holes, the white hole "would simply bounce away," Rovelli said. "They cannot swallow anything." If a black hole were to encounter one of these white holes, the result would be a single larger black hole, he added. As if the idea of invisible, microscopic white holes from the dawn of time were not wild enough, Rovelli and Vidotto further suggested that some white holes in this universe might actually predate the Big Bang. Future research will explore how such white holes from a previous universe might help to explain why time flows only forward in this current universe and not also in reverse, he said.

Rovelli and Vidotto detailed their findings online April 11 in a paper submitted to the Gravity Research Foundation's annual contest for essays on gravitation.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us