New Horizons' Dramatic Journey to Pluto Revealed in New Book

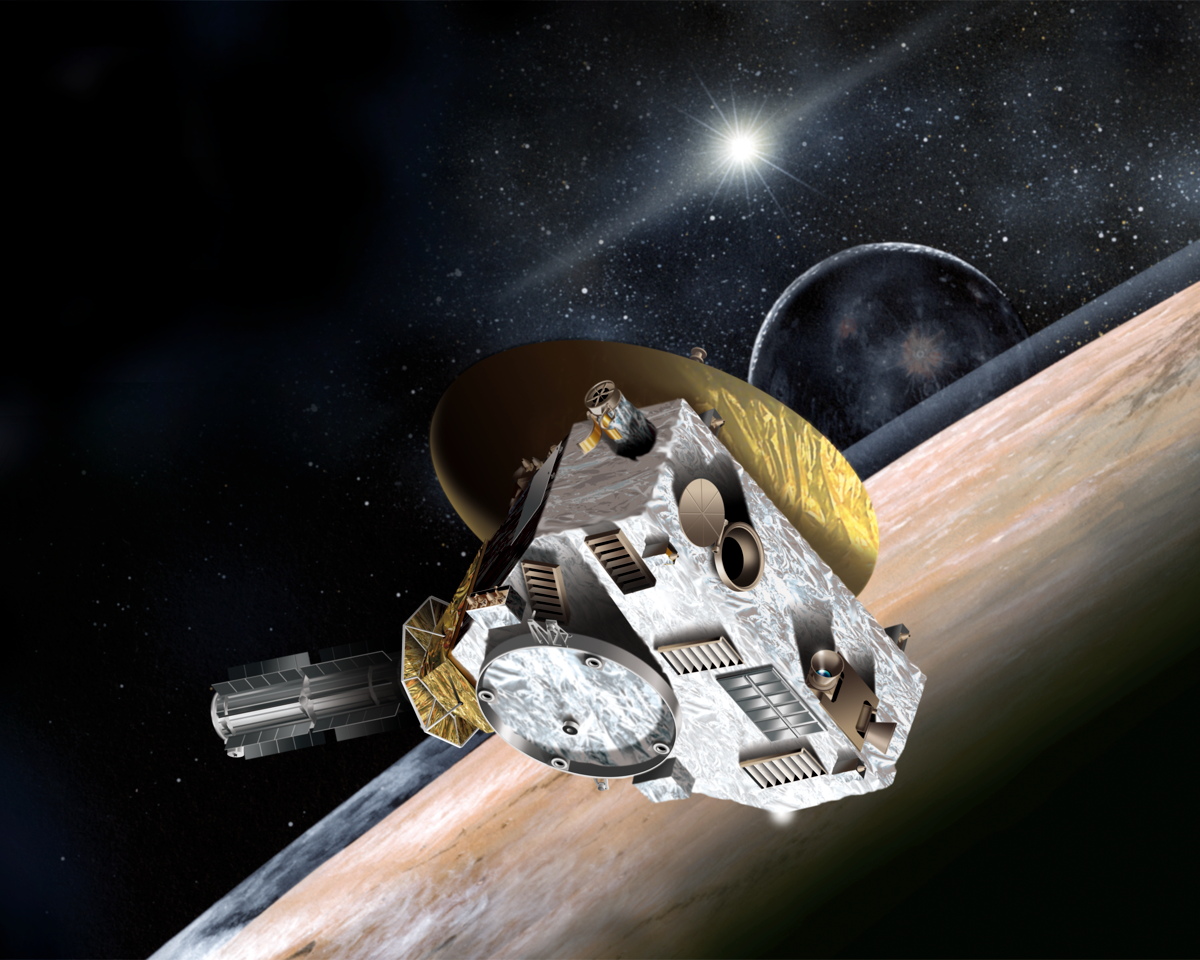

The groundbreaking New Horizons mission blazed past Pluto in 2015, transforming our view of the dwarf planet from just a speck to a complex world with changing geology, ice volcanoes, jagged spikes and more. But it almost didn't happen — time after time.

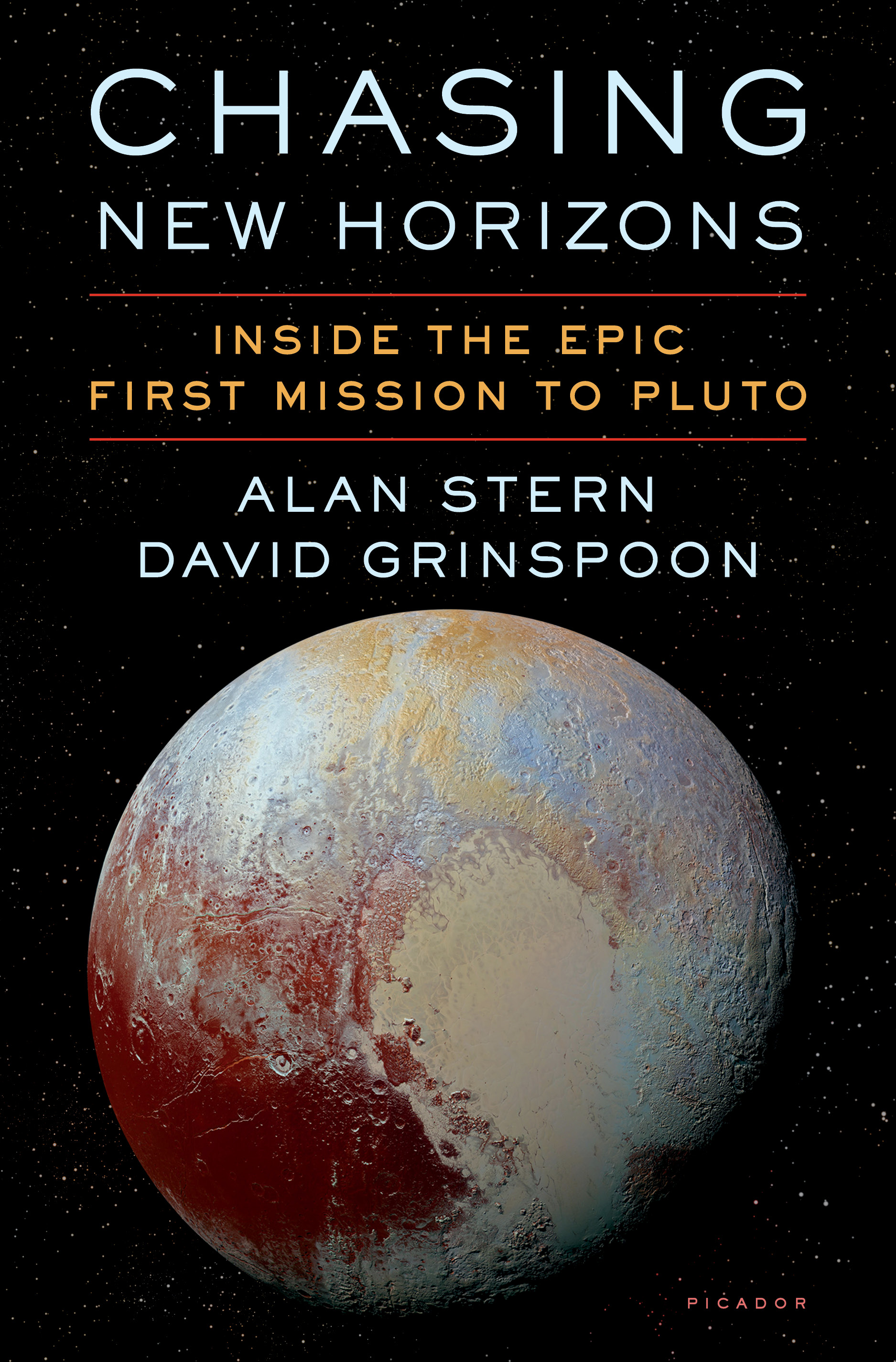

In "Chasing New Horizons" (Picador, 2018), out today (May 1), New Horizons' principal investigator, Alan Stern, joins astrobiologist David Grinspoon to tell the story of the lightweight spacecraft's challenging development and trip to the outer frontiers of the solar system. Their narrative delivers an in-depth view of how to design a space mission, shepherd it through the hurdles of approval and design, and send it toward the unknown when you have just one shot to get it right.

Space.com caught up with Stern to talk about the new book, the tough path New Horizons traveled before and after launch, the most amazing discoveries at Pluto, and the "Star Trek" test for planets. [We've Lost Contact: Read an excerpt from "Chasing New Horizons"]

Space.com: Would you say New Horizons' path was typical for this type of mission, or was it unique in how much trouble you had to go through?

Alan Stern: It was not typical. There are other missions that have had a tortured history for different reasons. But I think New Horizons is one of the longest and most involved, politically intriguing sagas in the history of planetary exploration, particularly for a first mission to a new planet. In the early days, they'd just say, "Well, we have the capability to go to Mars! Let's go to Mars! We have the capability to go to Venus — let's do that! Now we can do Jupiter!"

The idea of what we went through, which was a dozen years of study after study, committee after committee after committee, and ups and downs, and redesigns, all of that was just unprecedented. I hope that "Chasing New Horizons" brings that out but also does it in a way that it doesn't bog down. That was our goal.

Space.com: What was it like reliving every detail of the mission?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stern: It was actually a lot of fun. I got out old notebooks and photo albums, and David [Grinspoon, the book's co-author] did a lot of interviews with people. I did interviews with other people. Particularly [writing] the "dark ages" part, back in the '90s, when we were trying to get a mission to Pluto approved, required a good bit of historical research. But it was actually a lot of fun to do.

Space.com: Was there anything you wanted to include that didn't make it into the book?

Stern: Actually, a lot. When we first wrote the book and turned it in last summer, just after July 4, the publisher came back just weeks later and said, "This is a fantastic story, but it's too long — no one will read it. You're looking at 5[00] or 600 pages here that you guys wrote. You have to get it down into the range of 300 pages." And so, in squeezing the book down to make it more readable as it gallops along, a lot got left behind. Not the main tree trunk, the main story line. But there were lots of interesting details and some characters and some character development and more on the science, and if there's a second edition, we'll probably put some of that back in. If it does really well, and the publisher asks us to write an unabridged version, I know David and I would sign up for that.

Space.com: What is the legacy of New Horizons on planetary exploration?

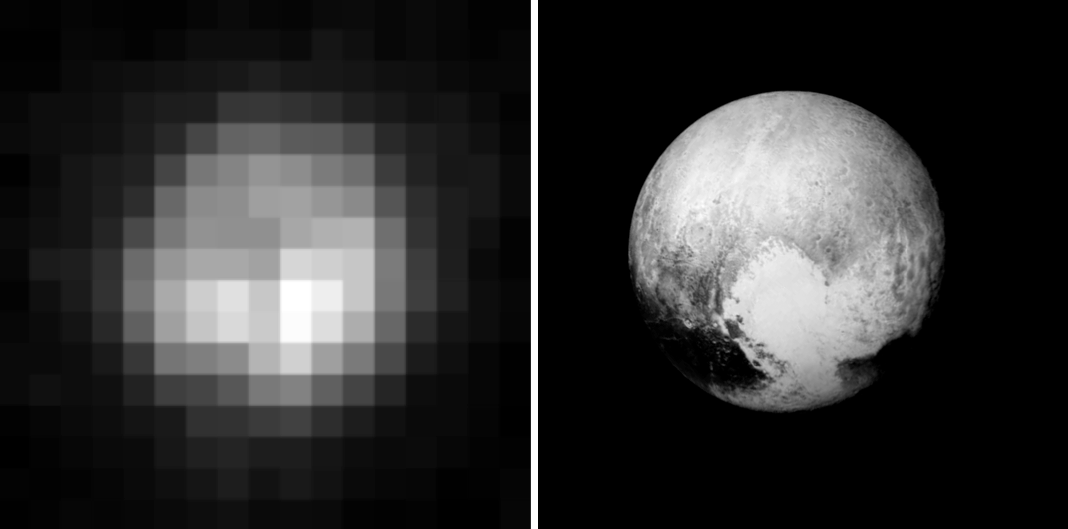

Stern: I think the legacy is several-fold. New Horizons was the first mission to a new planet since the late '80s. Forty percent of people in this country either weren't alive when Voyager went to Neptune or they were too young to remember it. It has been a generation. And when we explored Pluto and people loved it, loved and engaged in first-time exploration turning a point of light into a planet before their very eyes, almost overnight, it really showed NASA, again. And I think it showed people how exciting raw exploration is. As exciting as it is to go back to new places on Mars or to go back to Jupiter to study the satellites in more detail or what have you, the kind of exploration that New Horizons did, taking that point of light and turning it into a world, was way bigger on the Richter scale. That's one legacy.

Another legacy is that we showed how to build an outer-planets mission for two dimes on the dollar. Which is a huge cost breakthrough. Imagine if housing or car prices dropped to 20 percent of what they were. It means that it's possible to do a lot more missions by having them individually less expensive.

And then, third, by discovering that Pluto is so complicated and so diverse and active, it has really opened the eyes of the planetary science community to more Kuiper Belt exploration. Originally, [people] thought that going to Pluto was kind of the capstone event in the opening salvo of exploration of the planets. And today, it's viewed instead as the opening salvo of the next chapter, because we need to go to [the Kuiper Belt objects] Sedna, and Eris, and Makemake, and Ixion and Quaoar, and see that diverse population, which could be [as] diverse as the four terrestrial planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. And that's an important legacy, because the postdocs that were on New Horizons will be the PIs [principal investigators] of that kind of mission in the 2030s and 2040s.

Space.com: Do you think NASA will be able to do more exploration missions like this in the future?

Stern: I certainly think so. We have a Mars rover flagship that's being built for 2020. We have Europa Clipper in the final stages of design for launch in the mid 2020s. We're talking about Europa Lander, spending money to design it already — that's a flagship. And we can dial it up or down. We could go back to the Kuiper Belt and explore these other plants very easily, and we don't need flagships. Missions just like New Horizons in the New Frontiers series can do that. If we send a flagship back to the Kuiper Belt, it's probably going to be the Pluto orbiter. We could even combine the exploration of Uranus and Neptune with the exploration of the Kuiper Belt. There's a lot of talk about that. There's multiple communities sharing a single mission.

Space.com: Any of those you would be particularly excited to work on?

Stern: I would like to work on all of them. Why choose? It's just such exciting science. I am currently PI-ing a mission proposal to go to objects called Centaurs. They're escapees from the Kuiper Belt that orbit somewhat closer, between the giant planets. It's kind of a shortcut way to do the next set of Kuiper Belt science. I'm also working on that Pluto orbiter, as are a lot of other people. I'm very interested in the exploration of other dwarf planets with flyby missions that follow on the legacy of New Horizons. I think the future's really bright. I don't think we'll get all those things, but I think we will have some of those things, because New Horizons generated so much scientific interest in this region of the solar system and this class of planet. And I hope that "Chasing New Horizons" helps fuel that.

Space.com: And I have to ask about the planet thing — I apologize in advance. Do you think that Pluto's designation as a dwarf planet has affected the way we think about Pluto or our excitement at exploring it?

Stern: I don't think it affects the excitement of exploring it. NASA told us after the flyby that the public engagement from the internet and social media to front-page newspaper and magazine coverage for New Horizons was the biggest it had ever seen in the modern era. But I do think that what the astronomers did, this group that's not expert in planetary science, that [they] mislabeled dwarf planets as not planets when planetary scientists, the real experts, generally don't buy that. We recognize them as having all the characteristics of planets, just like Chihuahuas are still dogs. I have big black Labradors that weigh 60 and 80 lbs. [27 and 36 kilograms]. Those two girls are big dogs, but I have friends that have little, tiny dogs. They're all dogs, because genetically, they're connected. Similarly, Pluto and the dwarf planets are in the spectrum of what planetary scientists, the real experts, do call planets. I wish that the space and science journalists of today would think more critically about what astronomers did a decade ago, because journalists a decade ago just jumped on the controversy as opposed to science. And the fact that planetary scientists call these objects planets in published papers and in technical talks, in seminars and in their work, I think really tells the tale, and I hope that space journalists will get that word out.

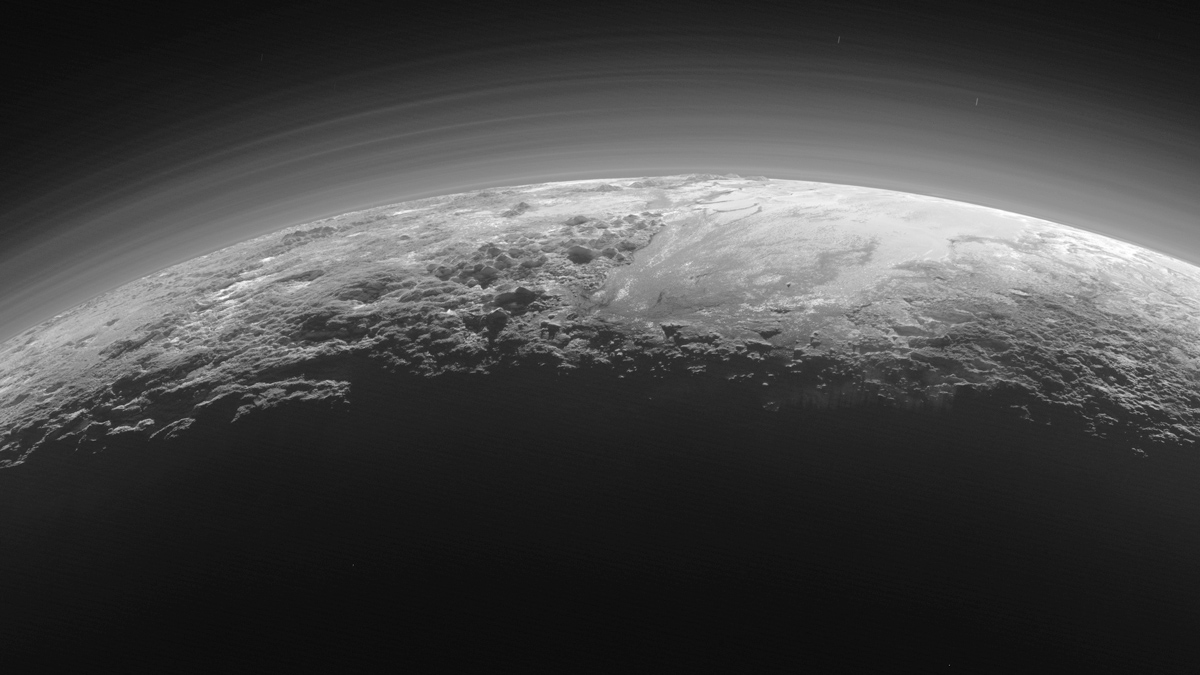

Space.com: It's hard to look at these photos from New Horizons and not think "that's a planet over there."

Stern: I always say in public talks that the simplest way to categorize planets is the "Star Trek" test. You're on the bridge of the Enterprise, the episode opens and Pluto's on the viewfinder, and what are you going to think? You're orbiting a planet. We don't know what else to call it. The fact that Pluto turned out to be as complicated as Earth or Mars, and it's active as any planet in the solar system from a geologic standpoint, just drives that point home further. I think the science that we discovered drives that point home further.

Space.com: What would you say is the most amazing discovery about Pluto from New Horizons?

Stern: I would rank two at the very top. … It's the complexity factor, that we did not anticipate that a small planet with the surface area of North America could be so complicated, as complicated as Mars or Earth, which are substantially larger planets. And secondly, that Pluto is so active geologically, 4 billion years after formation, defies all the textbooks. The textbooks said that small planets should cool off and its geologic engines die out early in its history. Here's the thing: Pluto didn't read the textbook. It's active on a massive scale. The big heart on the surface of Pluto is a glacier that has no craters on it, meaning it is geologically born yesterday. It's the size of Texas and Oklahoma combined, and somehow Pluto created it in the recent past, or is re-creating it all the time. Over and over and over, it's re-creating and erasing craters as they form. That level of activity was completely unexpected, and now it's changing our ideas about the very paradigms about how small planets are powered — all planets are powered, for that matter.

Space.com: What do you hope people draw from the story of this mission's development?

Stern: The story is really about five or six stories intertwined. There's the political story of how a mission to Pluto went through a lot of trials and tribulations. There's the story of how a bunch of young scientists with a lot of determination and grit, and a little bit of naiveté, managed to do it from scratch and push it through the system even when the system didn't want it, and ultimately triumph. In the flyby, clearly, there's a scientific story, there's a great insider story in there of how a spacecraft is designed and built and how to plan a flyby when you've only got one shot. And then there's the drama of the near-disaster 10 days before flyby [when the team suddenly lost contact with the spacecraft]. And all of that is woven by Grinspoon, in and out, in and out, as you go through the different chapters, you're getting updates on each part of that, but it's pretty seamlessly done.

Here's my secret wish: I hope they make a movie.

This interview has been edited for length. You can buy "Chasing New Horizons" on Amazon.com.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.