America's Space Prize: Reaching Higher Than Sub-Orbit

A new challenge awaits private rocketeers hoping to breach the space frontier with their own versions of reusable spacecraft, this one demanding faster and hardier vehicles capable of orbital flights.

America's Space Prize, a $50 million contest under development by Nevada millionaire Robert Bigelow, looks to push privately funded human spaceflight into orbit, and ultimately on missions to a planned space station.

But the competition poses significant challenges for any competitors that rise to the occasion, some of which include developing faster vehicles to escape Earth's gravity, hardier designs to withstand the reentry stresses and the tricky ability to dock with an orbiting facility.

"It's asking a lot," Bigelow told SPACE.com. "We're talking about a spacecraft that has rendezvous and docking capabilities, and that is a safe and reliable structure."

Bigelow's challenge takes a page from the recently won Ansari X Prize, which offered $10 million to the first private team to develop a reusable spacecraft capable of carrying humans to suborbital space twice in two weeks.

SpaceShipOne, a spaceplane developed by aviation pioneer Burt Rutan and financed by millionaire Paul Allen, clinched the X Prize during an Oct. 4 flight.

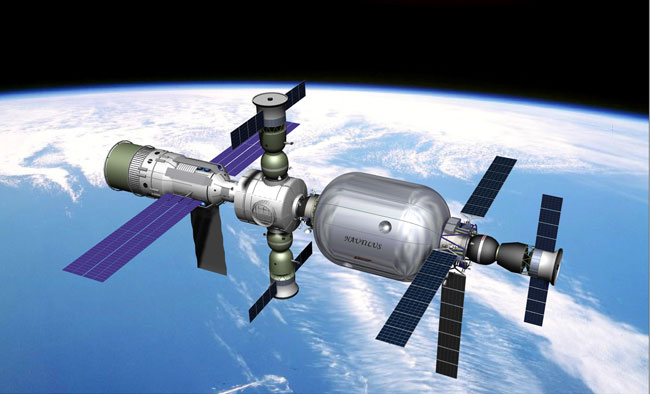

Like those that vied for the X Prize, Space Prize competitors would have to build a working spacecraft that could carry humans, reach a preordained altitude and repeat the feat during a given time period. Winners would snag the $50 million prize and first rights to service the Nautilus inflatable orbital modules under development by Bigelow Aerospace, Bigelow's Las Vegas-based firm.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's wonderful to see it happen," said Gregg Maryniak, executive director of the X Prize Foundation, of Bigelow's orbital challenge. "Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but we're making private spaceflight viable through these prizes."

Tougher challenges ahead

But challenging spacecraft designers to build their own orbital vehicles is a taller order than the suborbital gauntlet thrown by the X Prize.

"I think it's a good idea," said Brian Feeney, leader of the Toronto, Canada-based X Prize team GoldenPalace.com/da Vinci Project, of the orbital Space Prize.

Combined with the X Prize Cup, an annual suborbital spacefest planned by the developers of the Ansari X Prize, Bigelow's competition will spur the private spaceflight industry, he added.

Space Prize vehicles will be required to carry the weight of at least five people, two more than the suborbital X Prize. Depending on their launch configuration, they may have to be faster too.

NASA's space shuttles accelerate to about 18,000 miles an hour to attain Earth orbit and withstand reentry temperatures up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1648 degrees Celsius). Suborbital flights can be significantly slower, with. SpaceShipOne reaching about Mach 3 - Mach 1 is the speed of sound - or 2,600 miles (4,184 kilometers) an hour during its X Prize-winning flights.

"It's also a substantial distance, a substantial jump, to make from a suborbital flight to an orbital one," Bigelow said.

SpaceShipOne's Oct. 4 suborbital spaceflight hit a peak of 69.7 miles (112.2 kilometers), but an orbital spacecraft will have to reach altitudes in excess of 100 miles. The International Space Station (ISS) orbits the Earth at an altitude of about 250 miles (403 kilometers).

Then there's the cost, space experts say.

"I'd be very impressed if private entrepreneurs could get people to orbit for a reasonable amount of money," said Howard McCurdy, a space historian and professor of public affairs at American University in Washington, D.C.

Former astronaut and U.S. senator John Glenn's 1998 space shuttle seat cost NASA $50 million, and private orbital passengers like Dennis Tito and Mark Shuttleworth have paid about $20 million for jaunts to the International Space Station, McCurdy added. At present, British millionaire Sir Richard Branson's announcement of suborbital flights on his newly christened Virgin Galactic venture will cost around $190,000.

Building a destination

At the heart of the Space Prize is what Bigelow sees as a vital need for independent access to orbital space, especially since the grounding of the space shuttle fleet has left NASA dependent on other methods - such as the Russian Soyuz program - for launching humans into orbit.

"America has lost so much ground [in space]," he said. "Over time, we are going to be creating the first private space station."

According to Bigelow, the next three years will see launches of scaled versions of the Nautilus module, including one-third scale versions in 2005 and 2006, and a 45% version in 2007. A full-size Nautilus test flight could be ready by 2008, with a final version ready for the Space Prize in January 2010.

"There really wouldn't be a driving point if you had an orbital vehicle and it didn't have any particular place to go," he said, adding that space tourists, for example, might be unwilling to pay for long rides in cramped capsules. "You want to have freedom of movement."

One Nautilus module contains about 330 cubic meters. The habitable volume of the current ISS configuration is about 425 cubic meters.

Details to come

Ambitious as it is, there are still some fine points to put in place for the Space Prize, such as finalizing the funding.

Bigelow is committing $25 million of his own assets is seeking a partner to commit the remainder of the $50 million prize.

"Up until a few days ago, we thought we had pinned down the agency to participate in this prize," Bigelow said during a Sept. 30 interview, adding that discussions were pending.

Meanwhile, Bigelow and his Space Prize team plans to spend the next month and a half refining the rules for the Space Prize and look forward to what they hope to be an exciting competition.

"Aside from the space tourism and the fun and games, there is a very serious benefit to society and civilization in space," Bigelow said. "It's a real privilege to be part of that."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.