Scientists have found the spectral imprints of water vapor in starlight filtered through the atmosphere of a giant gas planet outside our solar system.

Combined with a study announced earlier this year, the new finding provides strong evidence that extrasolar planets are as rich in water as the worlds in our solar system, scientists say.

The finding is detailed in the July 11 issue of the journal Nature.

First solid evidence

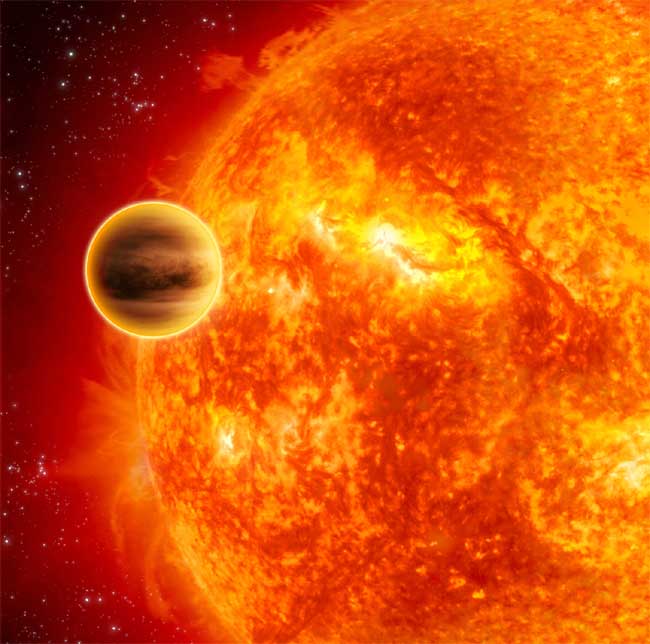

Called HD 189733b, the planet belongs to a class of gas giants called “hot Jupiters,” which orbit their stars from a distance closer than Mercury is to our sun. The fiery world is about 15 percent bigger than Jupiter and orbits a sun-like star located 64 light-years away in the constellation of Vulpecula, the Fox. It has an average temperature of 1,340 degrees Fahrenheit (727 degrees Celsius) and zips around its star in just two days.

“We’re thrilled to have identified clear signs of water on a planet that is trillions of miles away,” said study leader Giovanna Tinetti of the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris in France.

Heather Knutson, an astronomer at Harvard University, called the results “solid evidence” that hot Jupiters contain water.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“The detection comes as a relief for theorists who had predicted that water vapor should be a significant component of the atmospheres of hot Jupiters,” Knutson wrote in a related Nature article.

In April, astronomer Travis Barman of Lowell Observatory announced he had found evidence of water vapor in the atmosphere of another hot Jupiter using the Hubble Space Telescope and a technique similar to the one used by Tinetti’s team via the Spitzer Space Telescope. However, Barman’s results were such that they might have been caused by instrument noise, causing some scientists to be skeptical.

“Spitzer confirms [the Hubble results] by using an entirely different observatory and an entirely different wavelength,” said study team member Sean Carey of NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at Caltech.

“The two in combination are much stronger,” Carey told SPACE.com.

A second look

Scientists had previously looked for signs of water on HD 189733b but failed to find any. At the time, they suspected the water might be hidden beneath a thick layer of silicate clouds.

Tinetti and her team offer a different explanation. They hypothesize that unlike Earth, where the atmospheric temperature cools with altitude, the temperature of HD 189733b’s atmosphere is uniform over a range of altitudes.

In that previous study, the scientists looked for spectral absorption lines created by radiation traveling up from the interior of the planet and passing through layers of cool gas that selectively absorb certain wavelengths of light. Without a temperature difference, no absorption occurs.

In the new study, the researchers observed HD 189733b as it passed in front of, or “transited,” its parent star. Using Spitzer’s infrared camera, the team analyzed light that was emitted from the interior of the parent star and which passed through the planet’s atmosphere on its way to Earth. In this case, absorption occurs because of the temperature difference that exists between the star’s atmosphere and that of the planet.

The researchers found that the planet absorbed starlight in such a way that could only be explained by the presence of water vapor in its atmosphere.

Although water is an essential ingredient for life on Earth, HD 189733b and other hot Jupiters are unlikely to harbor any creatures due to their close proximity to their stars. But the new finding does make it more likely that other types of extrasolar planets also contain water, suggest the scientists.

“Finding water on this planet implies that planets in the universe, possibly rocky ones, could also have water,” Carey said.

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Hopes Dashed for Life on Distant Planet

- VIDEO: A World in the Habitable Zone

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.