Mysterious Medium-Size Black Holes May Lurk at the Centers of Small Galaxies

The hearts of small galaxies may hide a mysterious kind of black hole that has long proved elusive: medium-size black holes with masses between the mass of a few suns and that of millions of suns, a new study finds.

Over the decades, astronomers have detected many examples of two kinds of black holes: stellar-mass black holes and supermassive black holes. Stellar-mass black holes are up to a few times the sun's mass and are thought to arise when giant stars die and collapse in on themselves, whereas supermassive black holes are millions to billions of times the sun's mass and form the hearts of most, if not all, large galaxies.

Much remains unknown about the origins of supermassive black holes; they seem to have grown extraordinarily fast and appeared early in cosmic history, but researchers don't know exactly how. One theory involves intermediate-mass black holes — those with masses between 100 and 1 million solar masses — that previous research suggested might serve as the middle stages between stellar-mass and supermassive black holes. However, evidence for these missing links remains scant. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

Now, researchers say they may have detected 10 intermediate-mass black holes in the hearts of galaxies, including five that were previously unknown. These new findings suggest that intermediate-mass black holes may lurk within the centers of many small galaxies, the scientists said.

"Intermediate-mass black holes are ubiquitous in the local universe," study lead author Igor Chilingarian, an astronomer at both the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Moscow State University in Russia, told Space.com.

![Black holes are strange regions where gravity is strong enough to bend light, warp space and distort time. [See how black holes work in this SPACE.com infographic.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/8GbuLi8DVtx8HoZeSyndT7.jpg)

Black holes of any kind are challenging to spot because, as their name suggests, they are black, making them difficult to see against the blackness of space. One way to detect black holes indirectly is by looking for extraordinarily bright galactic cores. Prior work suggested that these so-called "active galactic nuclei" are likely black holes that unleash vast amounts of energy as gigantic clouds of gas "accrete" or fall into them.

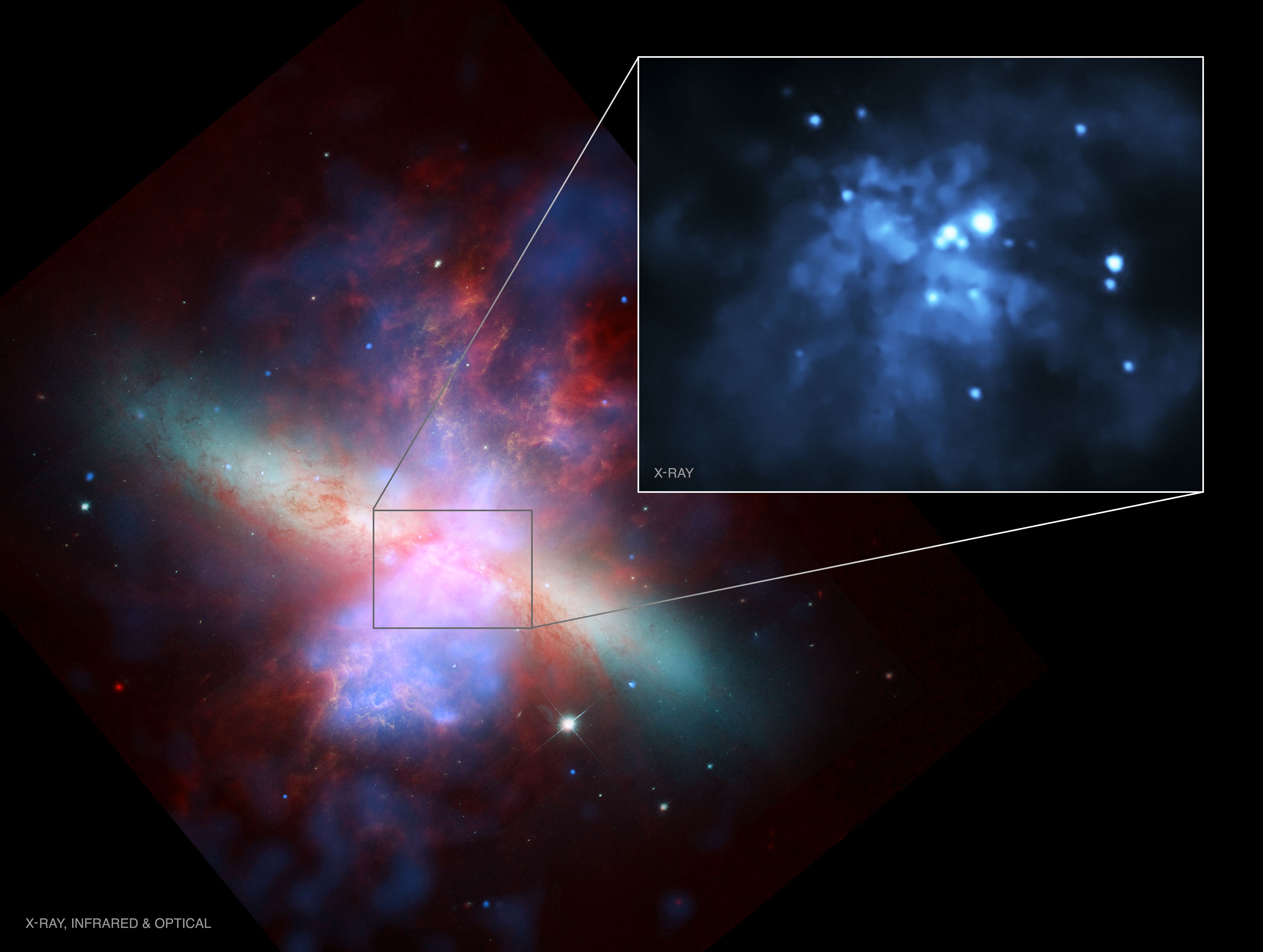

To hunt for intermediate-mass black holes, the new study's researchers first analyzed data on about 1 million galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, looking for the kind of light typically seen from accreting black holes. After they detected 305 potential intermediate-mass black holes residing in galactic cores, they searched data from the Chandra, XMM-Newton and Swift orbital X-ray observatories for X-rays that would serve as strong evidence that these candidates were, in fact, intermediate-mass black holes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"These are very faint sources of X-rays at the centers of galaxies," Avi Loeb, chair of astronomy at Harvard University, told Space.com. "Because they're faint, they can't be seen at great distances, so the researchers had to look at the nearby universe. It's very challenging to see these sources, because there are also stars at the centers of galaxies, and the researchers needed to distinguish these sources from stars all around it. This is why many of these sources were not seen before." Loeb was not involved with the new study.

The researchers detected 10 active galactic nuclei that they suggested were intermediate-mass black holes, ranging in mass from about 36,000 to 316,000 solar masses.

"These are the lowest-mass black holes at the centers of galaxies that we know about," Loeb said. "The detection of these intermediate-mass black holes in the centers of nearby dwarf galaxies indicates that you can, in fact, have black holes well below a million solar masses in size at the centers of galaxies."

The researchers found that the greater the masses of the intermediate-mass black holes were, the larger the central bulges of stars usually were in the galaxies that hosted them. A similar relationship is also seen with supermassive black holes, Loeb said. "This suggests the same process that builds black holes also builds galaxies; it starts with smaller galaxies and is seen in bigger galaxies," he said. [No Escape: Dive Into a Black Hole (Infographic)]

Loeb expected to see intermediate-mass black holes in the centers of many small galaxies. "If you go back in time to the early universe, these were the most common galaxies," Loeb said. "Galaxy formation is a hierarchical process; galaxies start small, and grow in mass by mergers and by accreting more matter."

Future research can explore how supermassive black holes originated. One possibility is that intermediate-mass black holes grew from stellar-mass black holes that rapidly devoured gas around them in the early universe, and that mergers of intermediate-mass black holes helped create supermassive black holes, Loeb said. Gravitational-wave observatories could detect such mergers in the future, he added.

However, there are other possible origins for both intermediate-mass and supermassive black holes that scientists need to explore, Loeb said. For instance, intermediate-mass black holes could have originated from the collisions of stars in extremely dense star clusters. In addition, black holes 100,000 to 1 million solar masses in size could have formed from collapsing massive gas clouds in the early universe, he added.

"The more we can learn about the origins of intermediate-mass and supermassive black holes, the more we can understand about the evolution of galaxies and the universe," Loeb said.

Chilingarian and his colleagues are now using one of the Magellan telescopes in Chile to improve their estimates of black-hole masses, and they hope to inspect 13 promising intermediate-mass black-hole candidates with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chilingarian also noted that, if the eROSITA X-ray space telescope launches as planned in 2019, "the number of confirmed intermediate-mass black holes will grow by an order of magnitude."

Chilingarian and his colleagues detailed their findings online May 3 in a study submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us