Days on Earth Are Getting Longer, Thanks to the Moon

Days on Earth are getting longer as the moon slowly moves farther away from us, new research shows.

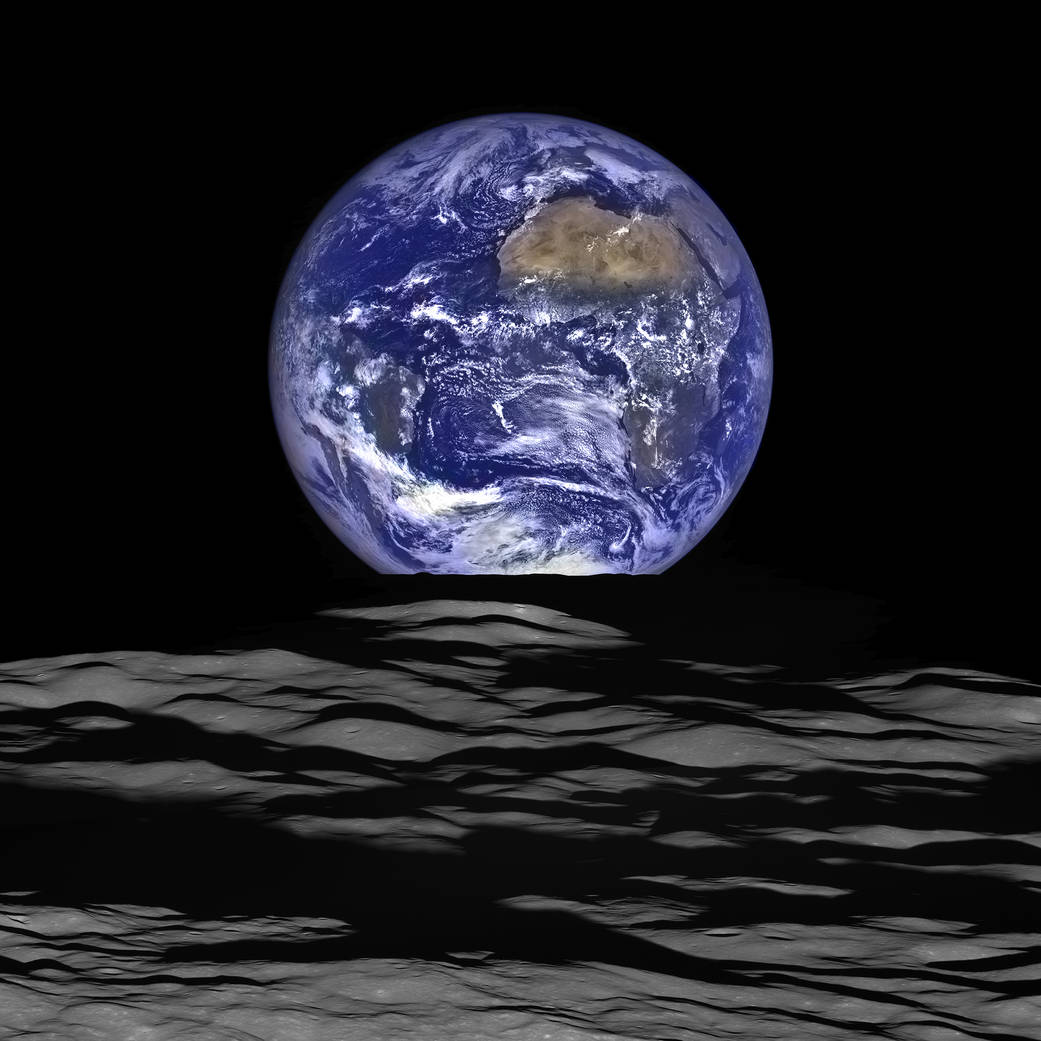

The moon is about 4.5 billion years old and resides some 239,000 miles (385,000 kilometers) away from Earth, on average. However, due to tidal forces between our planet and the moon, the natural satellite slowly spirals away from Earth at a rate of about 1.5 inches (3.82 centimeters) per year, causing our planet to rotate more slowly around its axis.

Using a new statistical method called astrochronology, astronomers peered into Earth's deep geologic past and reconstructed the planet's history. This work revealed that, just 1.4 billion years ago, the moon was significantly closer to Earth, which made the planet spin faster. As a result, a day on Earth lasted just over 18 hours back then, according to a statement from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Earth Quiz: Do You Really Know Your Planet?]

"As the moon moves away, the Earth is like a spinning figure skater who slows down as they stretch their arms out," study co-author Stephen Meyers, a professor of geoscience at UW-Madison, said in the statement. "One of our ambitions was to use astrochronology to tell time in the most distant past, to develop very ancient geological time scales. We want to be able to study rocks that are billions of years old in a way that is comparable to how we study modern geologic processes."

Astrochronology combines astronomical theory with geological observation, allowing researchers to reconstruct the history of the solar system and better understand ancient climate change as captured in the rock record, according to the statement.

The moon and other bodies in the solar system largely influence Earth's rotation, creating orbital variations called Milankovitch cycles. These variations ultimately determine where sunlight is distributed on Earth, based on the planet’s rotation and tilt.

Earth's climate rhythms are captured in the rock record, going back hundreds of millions of years. However, regarding our planet’s ancient past, which spans billions of years, this geological record is fairly limited, researchers said in the statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This can lead to some uncertainty and confusion. For example, the current rate at which the moon is moving away from Earth suggests that "beyond about 1.5 billion years ago, the moon would have been close enough that its gravitational interactions with the Earth would have ripped the moon apart," Meyers said.

Using their new statistical method, the researchers were able to compensate for the uncertainty across time. This approach was tested on two stratigraphic rock layers: The 1.4-billion-year-old Xiamaling Formation from northern China and a 55-million-year-old record from Walvis Ridge, in the southern Atlantic Ocean.

Examining the geologic record captured in the rock layers and integrating the measure of uncertainty revealed changes in Earth's rotation, orbit and distance from the moon throughout history, as well as how the length of day on Earth has steadily increased.

"The geologic record is an astronomical observatory for the early solar system," Meyers said in the statement. "We are looking at its pulsing rhythm, preserved in the rock and the history of life."

The new study was published Monday (June 4) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.