Surprise! Jupiter's Lightning Looks a Lot Like Earth's

Lightning storms on Jupiter are much more frequent, and much less alien, than previously thought, a pair of new studies suggests.

The first evidence of lightning on Jupiter was detected nearly 40 years ago. Electrical currents in lightning bolts generate a broad range of radio frequencies known as atmospherics, or "sferics" for short. And in 1979, NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft detected very low-frequency radio emissions from the solar system's largest planet — emissions that one might expect from lightning.

The radio emissions that Voyager 1 detected from Jupiter — dubbed "whistlers" because they resemble descending, whistled tones — were the first signs of lightning in the giant planet's atmosphere. Subsequently, cameras on NASA's Jupiter-orbiting Galileo spacecraft, the agency's Cassini Saturn probe (which cruised past Jupiter on its way to the ringed planet), and other spacecraft confirmed lightning on Jupiter in the form of flashes of light. [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

To shed light on Jupiter lightning, scientists examined data from NASA's Juno spacecraft, which is currently in orbit around the giant planet. They analyzed the largest database of lightning-generated whistlers collected from Jupiter to date.

The researchers detected more than 1,600 instances of lightning, nearly 10 times the number that Voyager 1 recorded. The scientists discovered peak rates of four lightning strikes per second, six times higher than the peaks that Voyager 1 detected.

"Lightning at Jupitercan be as frequent as on Earth," study lead author Ivana Kolmašová, of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, told Space.com.

"Given the very pronounced differences in the atmospheres between Jupiter and Earth, one might say the similarities we see in their thunderstorms are rather astounding," study co-author William Kurth, a space scientist at the University of Iowa, told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kolmašová, Kurth and their colleagues detailed their findings online today (June 6) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Lightning that sings the same tune

Previously, when spacecraft visiting Jupiter detected radio waves from lightning, they found only kilohertz emissions, or those of relatively low frequency. In contrast, lightning on Earth can produce gigahertz radio waves, which are millions of times higher in frequency.

This disparity suggested that lightning on Jupiter differed significantly from lightning on Earth; for example, prior work speculated that Jupiter lightning may discharge more slowly than lightning on Earth, or that something in Jupiter's atmosphere may absorb these higher frequencies.

In another new study, researchers again examined radio data from Juno, which passes up to nearly 50 times closer to Jupiter than Voyager 1 did, potentially allowing it to detect more radio waves. For the first time, the scientists detected radio waves from Jovian lightning that were megahertz in nature, or thousands of times higher in frequency than those previously seen.

"Jupiter's lightning may not be as different from Earth's lightning as we had thought," said Kurth, who was also a co-author on the second study.

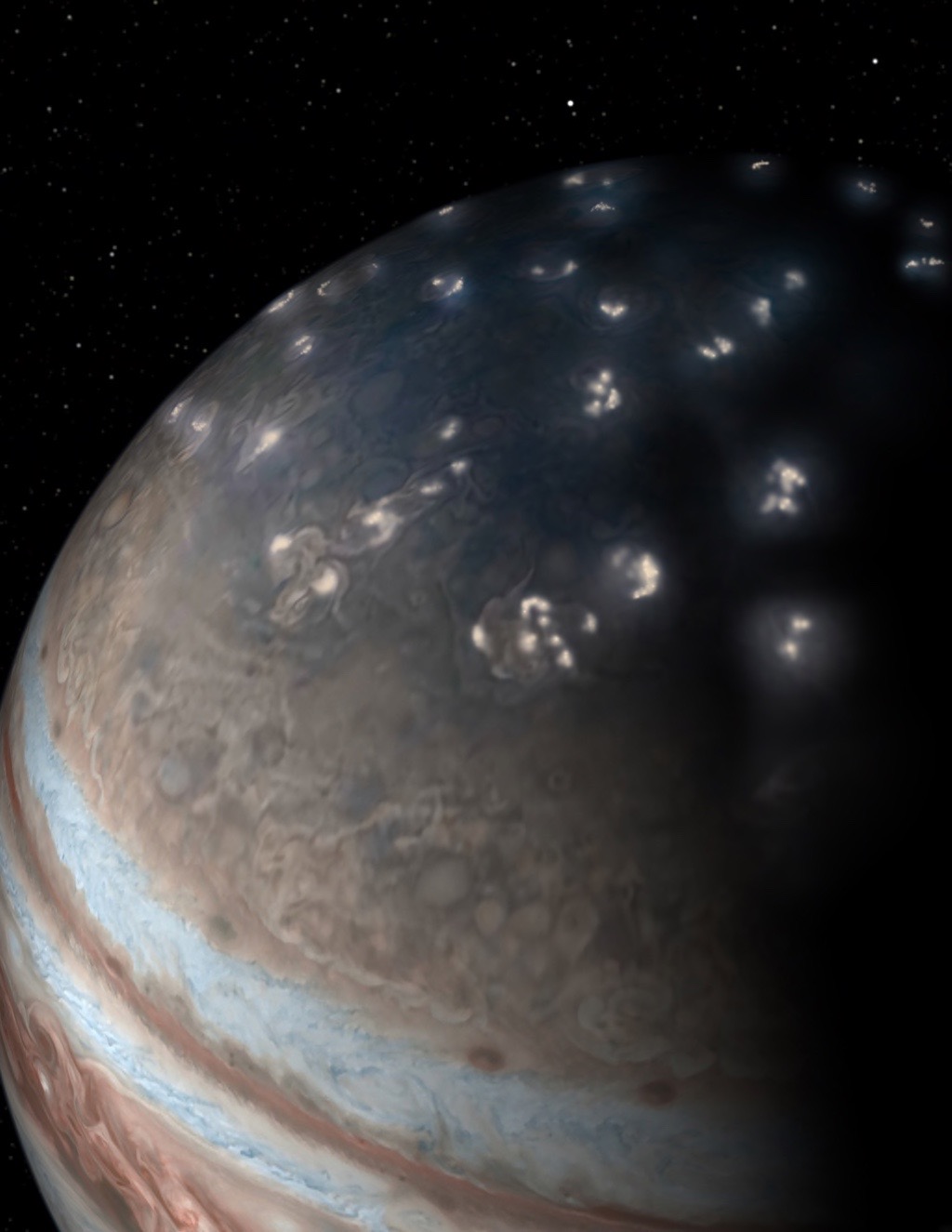

This research team also discovered that lightning on Jupiter appears more common near the poles, whereas it's absent at the equator. Jovian lightning is thought to originate from electrical interactions between water droplets and ice particles, much as it does on Earth, so these new findings suggest that water-laden gas in Jupiter's atmosphere circulates poleward, yielding insights into Jupiter's atmospheric composition and circulation.

"That distribution of lightning is kind of upside-down from what we'd expect on Earth," Kurth said. "On Earth, thunderstorms tend to cluster around low latitudes, and on Jupiter, it's the other way around."

The scientists also found that, oddly, lightning on Jupiter appears more common in the northern hemisphere than in the southern. The reason for this lopsided situation remains unclear, Kurth said.

Kurth, Kolmašová and their colleagues detailed the findings from the second study online today in the journal Nature.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us