Weird Low-Light Bacteria Could Potentially Thrive on Mars

An international team of scientists has found that a strange type of bacteria can turn light into fuel in incredibly dim environments.

Similar bacteria could someday help humans colonize Mars and expand our search for life on other planets, researchers said in a statement released with the new work.

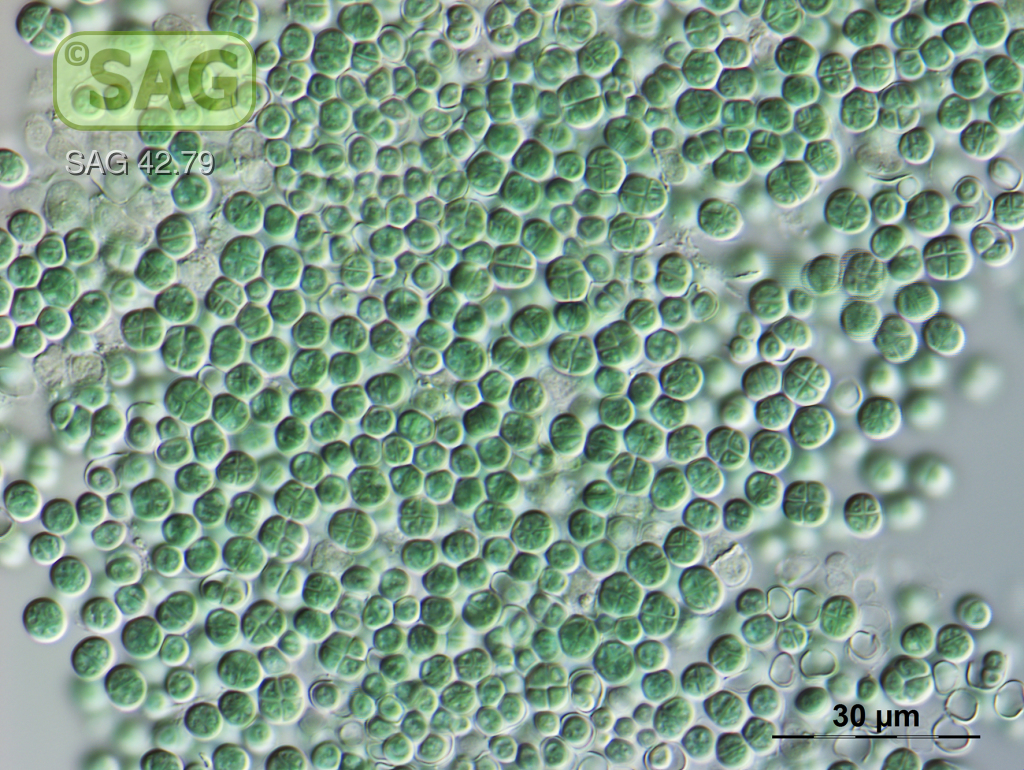

Organisms called cyanobacteria absorb sunlight to create energy, releasing oxygen in the process. But until now, researchers thought these bacteria could absorb only specific, higher-energy wavelengths of light. The new work reveals that at least one species of cyanobacteria, called Chroococcidiopsis thermalis — which lives in some of the world's most extreme environments — can absorb redder (less energetic) wavelengths of light, thus allowing it to thrive in dark conditions, such as deep underwater in hot springs. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"This work redefines the minimum energy needed in light to drive photosynthesis," Jennifer Morton, a researcher at Australian National University (ANU) and a co-author of the new work, said in the statement. "This type of photosynthesis may well be happening in your garden, under a rock." (In fact, a related species has even been found living inside rocks in the desert.)

By studying the physical mechanism behind these organisms' absorption abilities, researchers are learning more about how photosynthesis works — and raising the possibility of using similar low-light organisms to generate oxygen in places like Mars.

"This might sound like science fiction, but space agencies and private companies around the world are actively trying to turn this aspiration into reality in the not-too-distant future," Elmars Krausz, study co-author and a professor emeritus at ANU, said in the statement. "Photosynthesis could theoretically be harnessed with these types of organisms to create air for humans to breathe on Mars.

"Low-light-adapted organisms, such as the cyanobacteria we've been studying, can grow under rocks and potentially survive the harsh conditions on the Red Planet," Krausz added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers originally thought that a particular chlorophyll pigment, called chlorophyll f, helped capture light but couldn't directly participate in converting it into energy, according to the new work, which was released yesterday (June 14) in the journal Science. But this research shows that, in fact, the pigment does participate in energy conversion, and lets the organism pull energy from longer wavelengths than ever observed.

"Chlorophyll adapted to absorb visible light is very important in photosynthesis for most plants, but our research identifies the so-called 'red' chlorophylls as critical components in photosynthesis in low-light conditions," Morton said.

Not to mention, it could play a key role in the search for life beyond Earth: "Searching for the signature fluorescence from these pigments could help identify extra-terrestrial life," she said. Knowing such organisms exist on Earth not only broadens where we look for alien organisms but also suggests what to search for when we look.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.