To Improve Space Clothing, German Astronaut Will Work Up a Sweat

Alexander Gerst, a German astronaut for the European Space Agency, is about to sweat for science.

Gerst, who arrived at the International Space Station as part of the European Space Agency's Horizons mission on June 6, will help conduct the first experiments to explore how the human body, clothing and climate interact, in relation to comfort, under zero-gravity conditions.

Central to the study, known as SpaceTex2, will be the examination of three shirts, each with a different cooling performance, that were developed following the original SpaceTex experiments on the space station in 2014. [Spacesuit Suite: Evolution of Cosmic Clothes (Infographic)]

"Now it is the moment of truth — the examination of three shirts in space," Jan Beringer, a functional-textiles expert at Germany's Hohenstein Institute, which is managing the project, said in a statement. "We are all very excited about the results."

Gerst will have to perform six training sessions on the ergometer (space bicycle) or the treadmill while wearing the functional shirts. These sessions will happen outside of the 2 hours of exercise space station astronauts undergo daily to prevent bone and muscle loss.

Wearable sensors provided by the Institute of Aerospace Engineering at TU Dresden will pipe information about Gerst's respiratory flow, heart frequency and oxygen saturation back to Earth via a data downlink.

Gerst won't have an easy time of it, according to Beringer: "Gerst has to sweat quite a lot in space in order to activate the cooling performance of the functional shirts," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

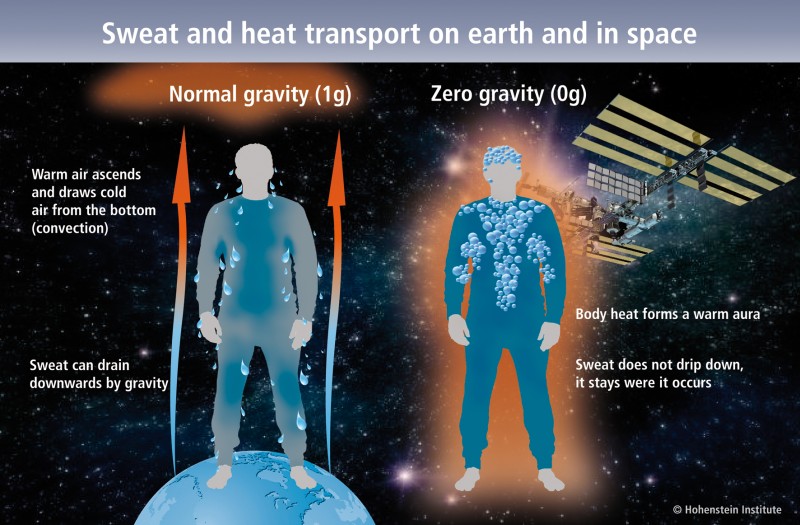

The shirts are necessary as conduits for heat exchange because sweating in space doesn't work quite the same way it does on Earth. Although an active human body will still attempt to cool itself through perspiration, sweat doesn't evaporate in the absence of gravity, and heat itself doesn't rise off the body.

"There is no loss of heat due to convection when in space," Beringer said. "During physical activity, heat thus builds up quicker than on Earth. The result of this is that the core body temperature rapidly climbs to values that are too high to be healthy."

Finding the right material to wick away sweat and keep a body cool is therefore vital for proper functioning in microgravity.

The findings will help scientists create optimized garments for intravehicular activity — which is to say, clothing worn inside the space station — according to the Hohenstein Institute, which is collaborating with the medical department of Charité University in Berlin, the German Aerospace Centre and ESA on the research.

At the same time, the study could provide valuable insight into the development of functional textiles for extreme climate and physiological conditions here on Earth, such as those potentially brought about by global warming, the institute noted.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jasmin Malik Chua is a fashion journalist whose work has been published in the New York Times, Vox, Nylon, The Daily Beast, The Business of Fashion, Vogue Business and Refinary29, among others. She has a bachelor's degree in animal biology from the National University of Singapore and a master of science in biomedical journalism from New York University.