Early Earth's Habitability Could Boost the Chances of Alien Life

The conditions on the early Earth have long been a mystery. But researchers from NASA and the University of Washington have now devised a way to account for the uncertain variables of the time, in turn discovering that our planet may have been more temperate long ago than previously thought.

By applying these findings to other rocky planets, the researchers conclude that the timeframe and likelihood of life persisting elsewhere is greater than first thought.

Given that we have no rocks or other material from Earth’s first 500 million years, approximations of conditions on our planet during that time have varied widely. Some picture early Earth as wracked by volcanic eruptions and bubbling with lava, while others envision a world asleep and encased in ice. [7 Theories About the Origin of Life on Earth]

Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history leaves room for many geological phases and "people have used all kinds of different geochemical datasets to get some measure of surface conditions," said the study’s lead author, Joshua Krissansen-Totton of the University of Washington.

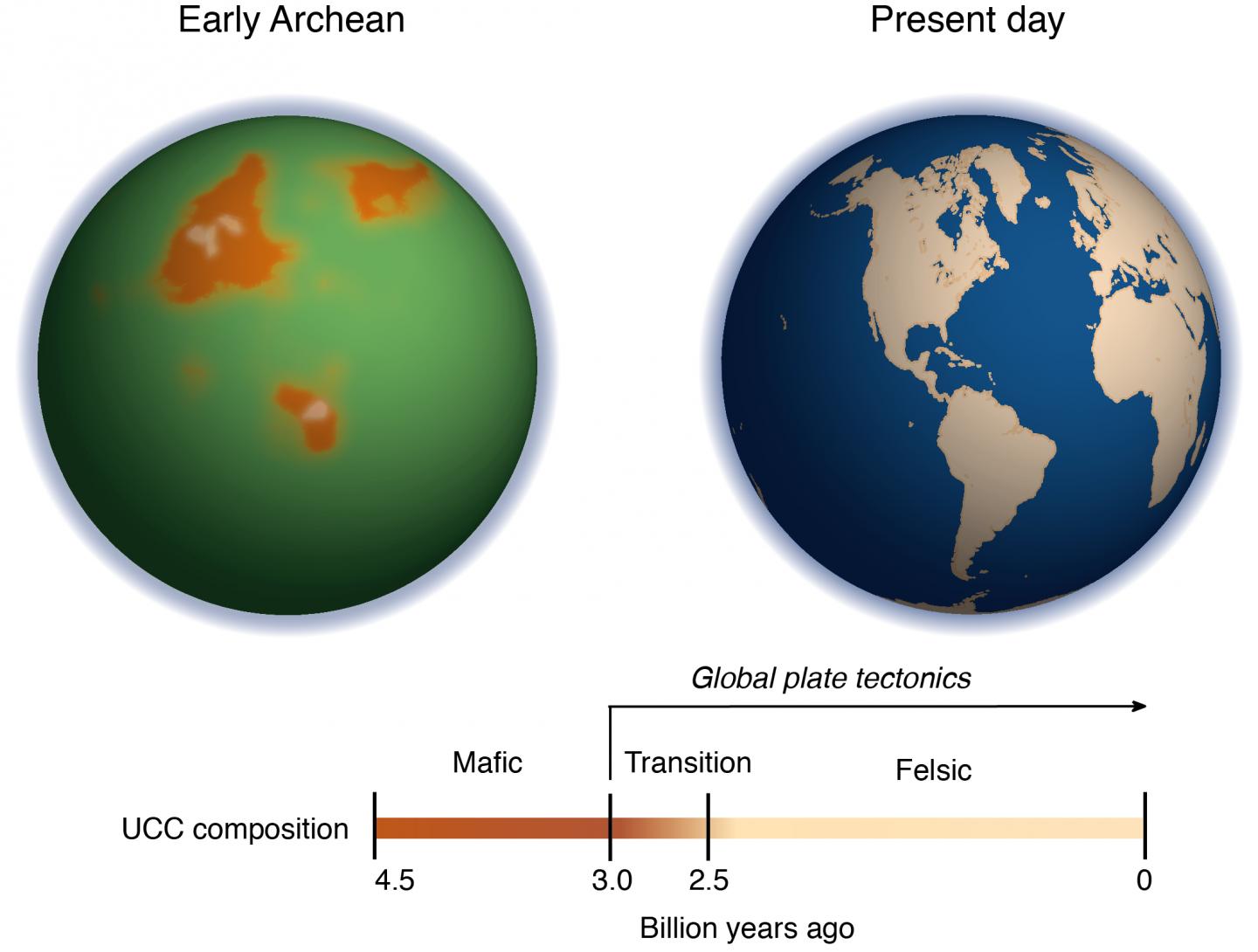

The researchers focused on the Archean Eon, 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago, shortly after the formation of Earth’s crust, atmosphere and oceans. It’s also when life likely emerged.

The difficult part is in deducing ocean pH and global temperature, about which estimates fluctuate drastically, from alkaline to corrosively acidic and from minus 13 to 185 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 25 to 85 degrees Celsius).

A natural thermostat

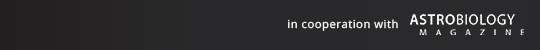

Earth’s carbon cycle holds the key to constraining these variables. Volcanos push carbon into the atmosphere by outgassing carbon dioxide; carbonic acid then rains down to the surface, dissolving rocks and releasing the ions inside, which eventually reach the oceans via rivers and form calcium carbonate.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The net result of this process is that carbon in the air is locked up in rocks. Similarly, seawater circulating through the ocean crust dissolves the surrounding rock, releasing ions that then form new carbonate rocks — a process that also locks up atmospheric carbon in the crust. Some of this carbon is subducted back into the planet’s mantle and starts the cycle anew as it’s outgassed again by volcanoes.

These weathering processes are temperature-dependent; Krissansen-Totton likened the effect to a "natural thermostat."

If carbon dioxide emissions increase, the temperature increases; if the temperature increases, seafloor weathering increases. Because it took billions of years to create Earth’s continents, less land existed on the early Earth, so seafloor weathering had a particularly significant regulatory impact on Earth’s temperature and vice versa.

Researchers applied their understanding of the carbon cycle based on data from the last 100 years and, instead of choosing any single theory regarding ocean composition and climate, they "picked the broadest range for the unknown and then calculated the range of possibilities for climate and ocean pH," Krissansen-Totton told Astrobiology Magazine.

"The researchers came up with new ways to describe how carbon in sediment and rock pore water is consumed by chemical reactions [in seafloor weathering]," explained Boston University Earth and Environment professor Andrew Kurtz, who was not part of the study.

A robust picture of early Earth

The researchers tested their model against the last 100 million years of Earth history, about which we know far more details, for a paper they published last year. This new study is the first to deploy a realistic and self-consistent representation of the process and to apply that to the early Earth, study team members said.

The simulations aren’t exact and don’t resolve all uncertainties. But, according to Krissansen-Totton, they provide "robust" information about early Earth. Kurtz affirmed that the results "produce a seemingly reasonably climate and pH history that is physically sensible and mathematically internally consistent."

The first half-billion years of the Earth’s life is a period called the Hadean Eon, so named because of its hellish heat. However, the study’s results challenge the notion that Earth remained scorching hot well into the Archean Eon. After the heat from Earth’s formation dissipated, the researchers’ models suggest that the climate and ocean pH were surprisingly moderate: between 32 and 122 degrees Fahrenheit (0 to 50 degrees Celsius), with a pH of between 6.2 and 7.7. (A pH of 7 is neutral.)

Kurtz noted that this result is consistent with aninfluential 2002 paper arguing the likelihood of a "cool early Earth."

Krissansen-Totton believes the regulatory carbon/seafloor weathering process would occur on any rocky planet with water. "There’s nothing special about these processes," he said. We know that pre-solar nebulae contain the ingredients for life; we also know countless exoplanets with those ingredients exist in the "habitable zones" of their stars. The study widens the window of time on which life could have emerged on those planets. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

More opportunities for life

The model doesn’t resolve debates about exactly when or where life emerged, but it steers scientists in productive directions for further research. For example, "if you believe life on Earth started at high temperatures, that could still be true," Krissansen-Totton said, "but that would restrict origins to locally warm environs like hydrothermal vents."

The study also has implications for planetary evolution. Kurtz pointed out that "Mars once had most of what Earth has going for it, or so we think: water on the surface, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and silicate rocks," a combination that seems to support the possibility that life could once have existed there.

Scientists believe Mars’ atmosphere was lost to space via the solar wind, but questions remain as to what upset the Red Planet’s cyclical balance, as well as whether other planets could experience such drastic conditional changes.

The new study was published in April in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The work was supported by NASA Astrobiology through the Exobiology & Evolutionary Biology Program and the Virtual Planetary Laboratory, as well as through the Earth and Space Science Fellowship program.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. This version of the story published on Space.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.