1st Satellite Built to Harpoon Space Junk for Disposal Begins Test Flight

The first spacecraft to demonstrate active space debris-removal technologies — such as a harpoon, a net and a drag sail — in orbit has been released from the International Space Station to commence its mission.

Astronauts at the space station sent the 100-kilogram (220 lbs.) RemoveDebris spacecraft off for its pioneering mission using Canadarm2, the 17.6-meter-long (57.7 feet) robotic arm used for servicing and capturing cargo ships.

The spacecraft is the largest payload deployed from the space station, according to NanoRacks, the Houston-based company coordinating RemoveDebris' deployment. The spacecraft drifted away from the orbital outpost at about 11:30 p.m. BST (7:30am EDT) on Wednesday, June 20. [7 Ways to Clean Up Space Junk]

Engineers at the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom confirmed about 2 hours later that they had contacted the spacecraft from their facilities in Guildford, Surrey, a small town in southern England.

The ground controllers will spend the next two months switching on all the satellite's subsystems and checking that they work as designed, according to Guglielmo Aglietti, director of the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey and principal investigator of the European Union-funded, 5.2-million-euro ($18.7 million) mission.

"We expect to start with the experiments at some point in September," Aglietti told Space.com. "We will need three to four weeks for each experiment. That's because we want to capture a high-definition video of each experiment, and to have a nice video, you need to wait for the spacecraft to be in the right position and to have the right illumination."

European aerospace giant Airbus designed and built three of the four planned experiments aboard the spacecraft. The debris-catching net experiment, developed at Airbus' site in Bremen, Germany, will be conducted in October, the company said in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

First, the main RemoveDebris spacecraft will release a small cubesat and let it drift away to a distance of about 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 feet). Then, the main spacecraft will eject the net in an attempt to capture the cubesat.

In December, RemoveDebris will test vision-based navigation technology developed by Airbus in Toulouse, France. The technology will use a set of 2D cameras and a 3D lidar technology to track a second cubesat as it floats away from the main satellite.

In February 2019, the last of Airbus' three experiments will take place. RemoveDebris will fire a pen-size harpoon into a panel that will deploy from the main spacecraft attached to a boom.

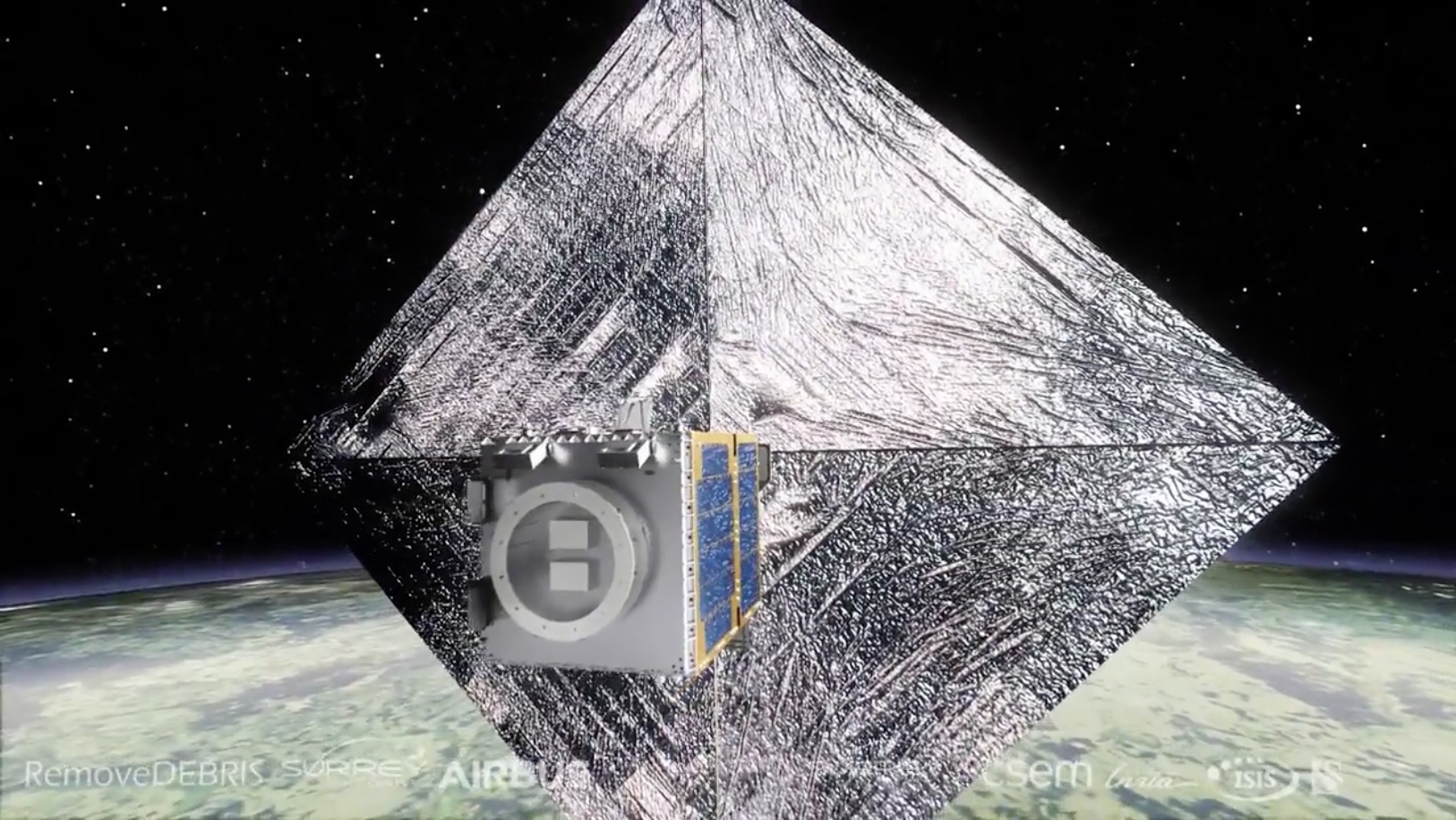

Finally, at some point in March 2019, the RemoveDebris spacecraft will deploy a drag sail, developed by the Surrey Space Centre, which will speed up the satellite's deorbiting process.

"The sail produces a significant amount of drag so that the spacecraft slows down and its orbit decays much faster than it would without the sail," said Aglietti.

"We expect that RemoveDebris will deorbit in less than 10 weeks," he said. "Without the sail, it could take 100 weeks or even more."

Aglietti said he expects the space industry to closely watch the experiments. Space debris is a growing problem, and the world's space agencies agree that steps must be taken to tackle the issue. Using drag sails more widely, Aglietti said, would reduce the amount of time defunct satellites stay in orbit, thus reducing the risk that they'll collide with other spacecraft.

Active space debris-removal technologies, such as harpoons and nets, are becoming increasingly important as well. Even if everyone complied with the regulations, it still wouldn't be enough, experts say. Satomi Kawamoto, of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), said in a conference last year that more than 100 objects need to be removed from LEO at the rate of five per year to stop the proliferation of fragments resulting from in-orbit collisions and explosions.

"We have done a lot of testing on the ground, but this will be the first time that these technologies will be tested in space," said Aglietti. "We cannot reproduce the situation in orbit on the ground 100 percent. For us, whatever happens during the mission will be a learning experience. We will be able to see for the first time how these technologies work in the space environment."

The European Space Agency (ESA) originally considered using the harpoon and net for its e.Deorbit mission, which will attempt to remove Envisat, a bus-size Earth-observation satellite that died in 2012. It's one of the largest and most dangerous pieces of space junk in low Earth orbit.

However, the agency later decided to use a robotic arm instead of the harpoon and net, as the arm can be repurposed for orbital servicing missions, Luisa Innocenti, head of ESA's Clean Space Initiative, said last year.

Aglietti, however, said he hopes that if the RemoveDebris experiments are successful, other players will take the technologies to the next level.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.