Asteroid Arrival! Japanese Probe Reaches 'Spinning-Top' Space Rock Ryugu

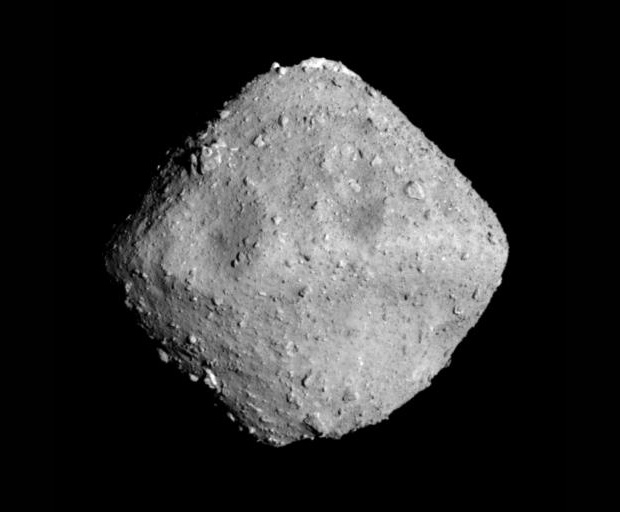

The Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2 has successfully rendezvoused with Ryugu, beginning an 18-month stay at the diamond-shaped asteroid.

Launched by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA, in 2014, the probe will poke, prod and even impact the asteroid, deploying a small lander and three rovers. It will then blast an artificial crater to analyze material below the asteroid's surface. After that, the probe will head back to Earth, arriving near the end of 2020 with samples in tow.

Hayabusa2 automatically fired its thrusters this morning (June 27) at 9:35 a.m. local Japanese time (8:45 p.m. on June 26 EDT, or 1245 GMT), bringing the probe within a constant 12 miles (20 kilometers) of the asteroid, according to a statement from JAXA. [Funny (and Scary) Ryugu Predictions by Japan's Hayabusa2 Team]

"From this point, we are planning to conduct exploratory activities in the vicinity of the asteroid, including [conducting] scientific observation of asteroid Ryugu and surveying the asteroid for sample collection," JAXA officials said in the statement.

The Hayabusa2 team will have to select the best place for the probe's lander and rovers based on the space rock's spinning-top-like shape and its rotation; the 3,000-foot-wide (900 meters) asteroid rotates perpendicular to its orbit, completing a full rotation every 7.5 hours.

"Now, craters are visible, rocks are visible and the geographical features are seen to vary from place to place. This form of Ryugu is scientifically surprising and also poses a few engineering challenges," Hayabusa2 Project Manager Yuichi Tsuda said in a statement before the asteroid's arrival.

The lander on Hayabusa2, called MASCOT(short for Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout), was built by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) as part of a joint German-French contribution to the mission. The lander is scheduled to be released by Hayabusa2 in October. After landing, MASCOT will hop around the asteroid, covering distances of up to 229 feet (70 meters), to study different parts of the asteroid. It is expected to last at least 16 hours, DLR officials have said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As far as we are concerned, Ryugu is an ideal test object for us, as it is only 900 meters in diameter and there are many members of the same asteroid class in near Earth orbits," Ralf Jaumann of DLR's Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin said in a statement. "Its unusual, angular shape, revealed in the latest images, is exciting."

The asteroid's shape and rotation "means we expect the direction of the gravitational force on the wide areas of the asteroid surface to not point directly down," Tsuda added. "We therefore need a detailed investigation of these properties to formulate our future operation plans." [Photos: Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Mission in Pictures]

JAXA's first Hayabusa mission brought back dust from the surface of the asteroid Itokawa in 2010; Hayabusa2 will go deeper on Ryugu than the first mission did on Itokawa, blasting the diamond-shaped asteroid with a cannon and spiraling down to collect samples. The estimated cost of the Hayabusa2 mission is 16.4 billion yen ($150 million), according to JAXA.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.