Weird Bright Spots on Ceres Get a Close-Up from Dawn As Mission Nears End

NASA's Dawn spacecraft has gotten its best-ever looks at the weird bright spots that speckle the dwarf planet Ceres.

Early last month, Dawn maneuvered its way to a new orbit around Ceres, an elliptical path that takes the probe within a mere 21 miles (34 kilometers) of the dwarf planet on nearest approach. That's more than 10 times closer than Dawn had gotten previously during its three-plus years at Ceres.

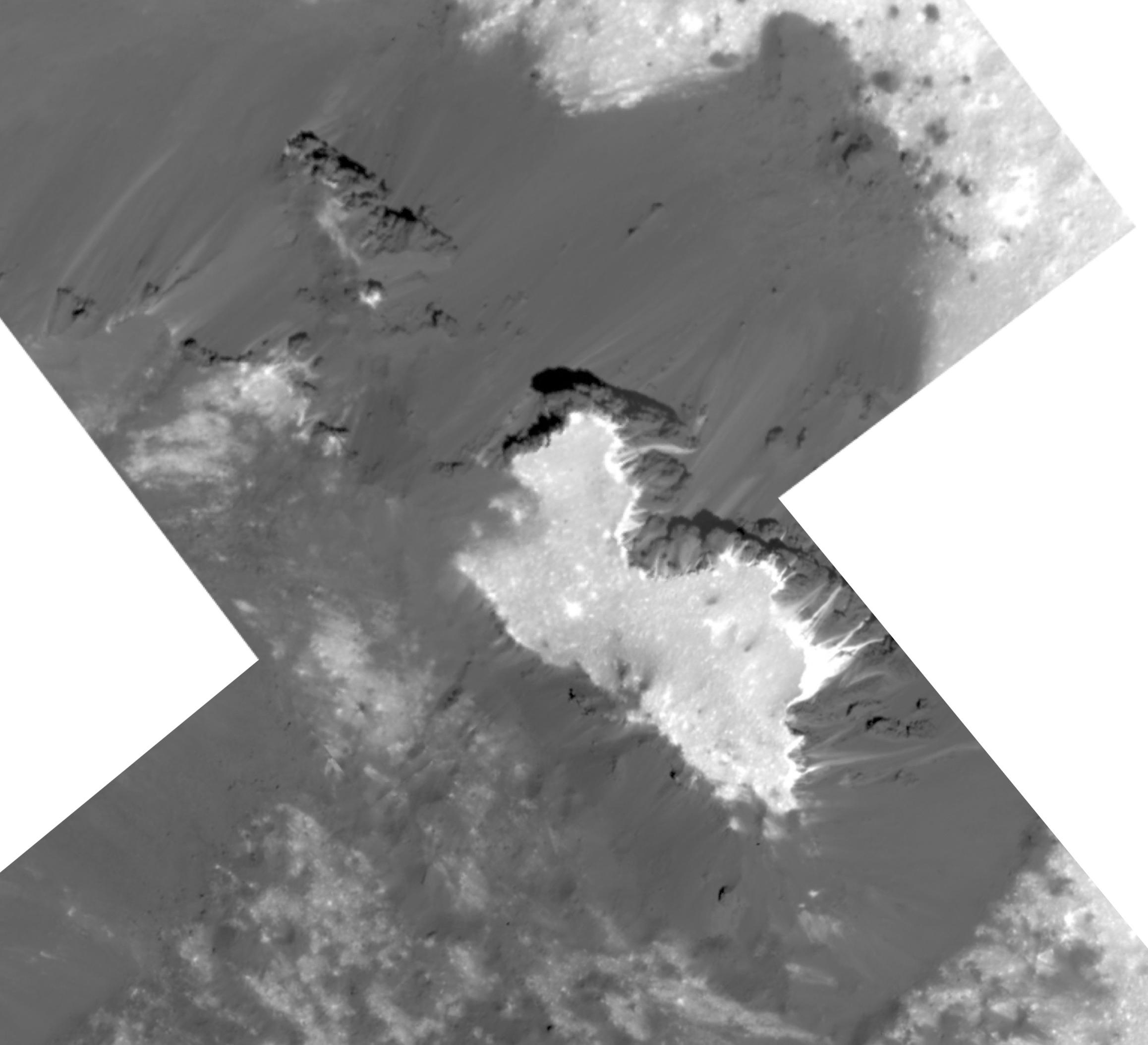

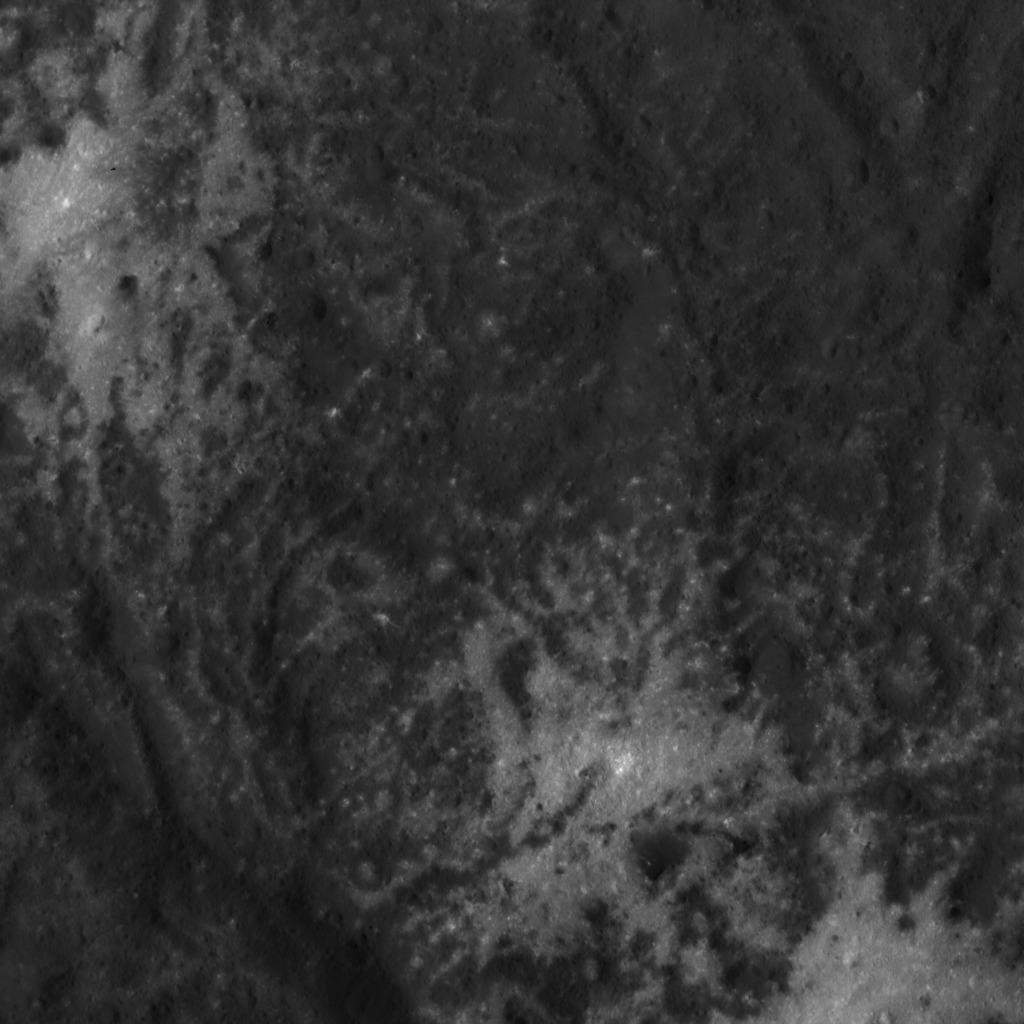

The views from this low altitude are amazing, as some newly released imagery of the 57-mile-wide (92 km) Occator Crater shows. [In Pictures: The Changing Bright Spots of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

Occator's floor hosts odd bright deposits, which Dawn discovered during its approach to Ceres in early 2015. Subsequent observations by the probe revealed that the bright stuff, which also occurs at several other locations around Ceres, consists of sodium carbonate.

Scientists think this material was left behind when salty water boiled away into space. But it's unclear where exactly that water came from. Was it concentrated in reservoirs near the surface? Or did it snake up to the surface via fissures from deep underground?

The newly released photos of Occator, which Dawn captured on June 14 and 22, could shed light on this mystery by painting a more complete picture of the crater floor, mission team members said.

"Acquiring these spectacular pictures has been one of the greatest challenges in Dawn's extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition, and the results are better than we had ever hoped," Dawn chief engineer and project manager Marc Rayman, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "Dawn is like a master artist, adding rich details to the otherworldly beauty in its intimate portrait of Ceres."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007 with an ambitious goal: to orbit and study Vesta and Ceres, the two biggest objects in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Vesta and Ceres — which are 330 miles (530 km) and 590 miles (950 km) wide, respectively — are building blocks left over from the solar system's planet-formation period, which explains the mission's name.

Dawn orbited Vesta from July 2011 through September 2012, when it departed for Ceres. The probe arrived at the dwarf planet in March 2015, becoming the first spacecraft ever to orbit two objects beyond the Earth-moon system.

Dawn's storied mission is nearing the end; last week, the spacecraft fired its superefficient ion engine for likely the final time. Dawn is low on hydrazine, the fuel that powers the probe's smaller, orientation-controlling thrusters. When the hydrazine runs out in September or thereabouts, Dawn will be done; it won't be able to point its scientific instruments at Ceres or its antenna toward Earth to communicate.

"The first views of Ceres obtained by Dawn beckoned us with a single, blinding bright spot," Dawn principal investigator Carol Raymond, also of JPL, said in the same statement. "Unraveling the nature and history of this fascinating dwarf planet during the course of Dawn's extended stay at Ceres has been thrilling, and it is especially fitting that Dawn's last act will provide rich new data sets to test those theories."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.