Life on Mars Could Have Gotten an Early Start, 'Black Beauty' Meteorite Suggests

It didn't take long for Mars to become a potentially habitable world, a new study suggests.

The planet-formation process generates a lot of heat, so rocky worlds such as Mars and Earth are covered by oceans of molten rock shortly after they form. Life as we know it cannot get a foothold until these oceans freeze into a crust — and this apparently happened quite early on the Red Planet, the new study reports.

"Already 20 million years after the formation of the solar system, Mars had a solid crust that could potentially house oceans and perhaps also life," study co-author Martin Bizzarro, director of the Center for Star and Planet Formation at the Natural National History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, said in a statement. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

That's about 130 million years sooner than this key event occurred here on Earth, study team members said.

The researchers — led by Laura Bouvier and Maria Costa, both also of the Center for Star and Planet Formation — studied tiny pieces of an 11.3-ounce (320 grams) Mars meteorite known as "Black Beauty," which was discovered in the Sahara Desert in 2011.

A year ago, Bizzarro acquired 1.55 ounces (44 grams) of Black Beauty (whose official name is NWA 7034) — no small feat, given that pieces of the space rock sell for about $10,000 per gram. (Bizzarro pulled it off by getting funding help from several sources and exchanging meteorites from the Natural National History Museum of Denmark's collection.)

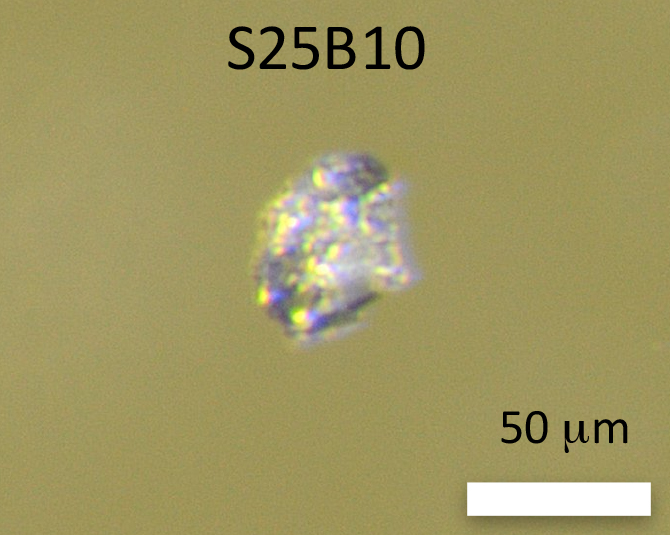

The team then crushed about 0.18 ounces (5 grams) of their Black Beauty bits to get a detailed look at its zircons, hardy minerals that scientists often use to figure out the precise age of samples. (This is done by measuring how much of zircons' native uranium has radioactively decayed into lead — a process that occurs at a regular and well-understood rate.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Zircon also acts as a small time capsule, as it preserves information about the environment where and when it was created," Bizzarro said in the same statement.

The researchers isolated seven zircons, which they found had formed between 4.43 billion and 4.48 billion years ago. The oldest of these seven is the most ancient Martian material ever dated directly, study team members said.

The team then analyzed the isotopic composition of another element in the zircons, called hafnium. (Isotopes are varieties of an element that have different numbers of neutrons in their atomic nuclei.) This hafnium must originally have come from a solidified Martian crust, which the researchers' work suggested had formed no later than 4.547 billion years ago — just 20 million years after the solar system's birth.

"Thus, a primordial crust existed on Mars by this time and survived for around 100 Myr [million years] before it was reworked, possibly by impacts, to produce magmas from which the zircons crystallized," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published last week in the journal Nature.

Scientists have already determined that at least some parts of the Red Planet were likely capable of supporting Earth-like life long ago. NASA's Curiosity rover, for example, discovered that Mars' Gale Crater hosted a long-lived lake-and-stream system in the ancient past.

But things changed greatly when Mars lost its global magnetic field around 4 billion years ago. The solar wind began stripping the planet's once-thick atmosphere, and the world transitioned to the cold, dry desert it is today.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.