NASA's Historic Mission to the Sun Gets a Heat Shield

NASA engineers are one step closer to understanding the "crown" of the sun.

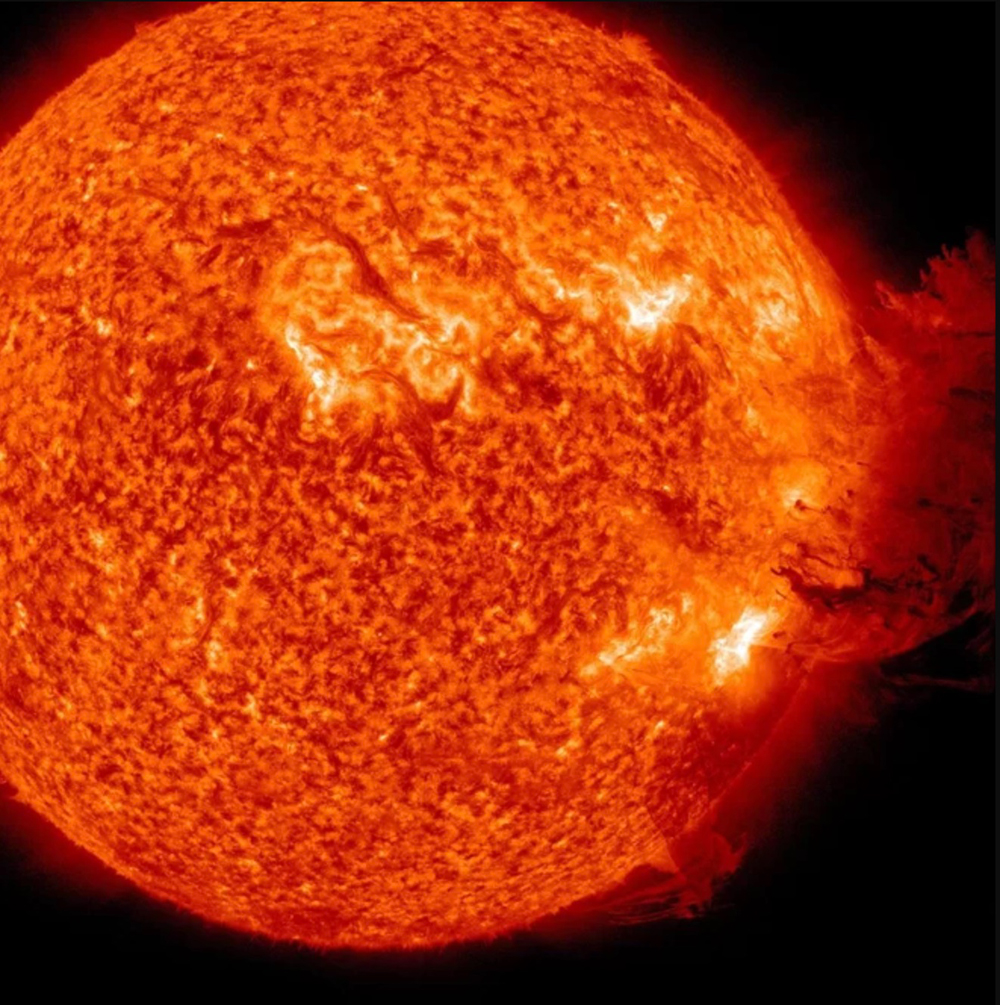

In photographs of total solar eclipses, the ethereal halo an observer sees is the sun's corona. The word means "crown" in Latin and Spanish, but the beauty of the name masks a scorching reality: 500 kilometers from the sun's visible surface, coronal temperatures can reach a few million degrees.

This environment makes the sun a hostile world to study. So to ensure a new NASA mission to the sun succeeds, engineers added protection to the spacecraft, according to a new statement from the space agency. [Get Ready for 2 Solar Eclipses Coming to the US in 2023 and 2024]

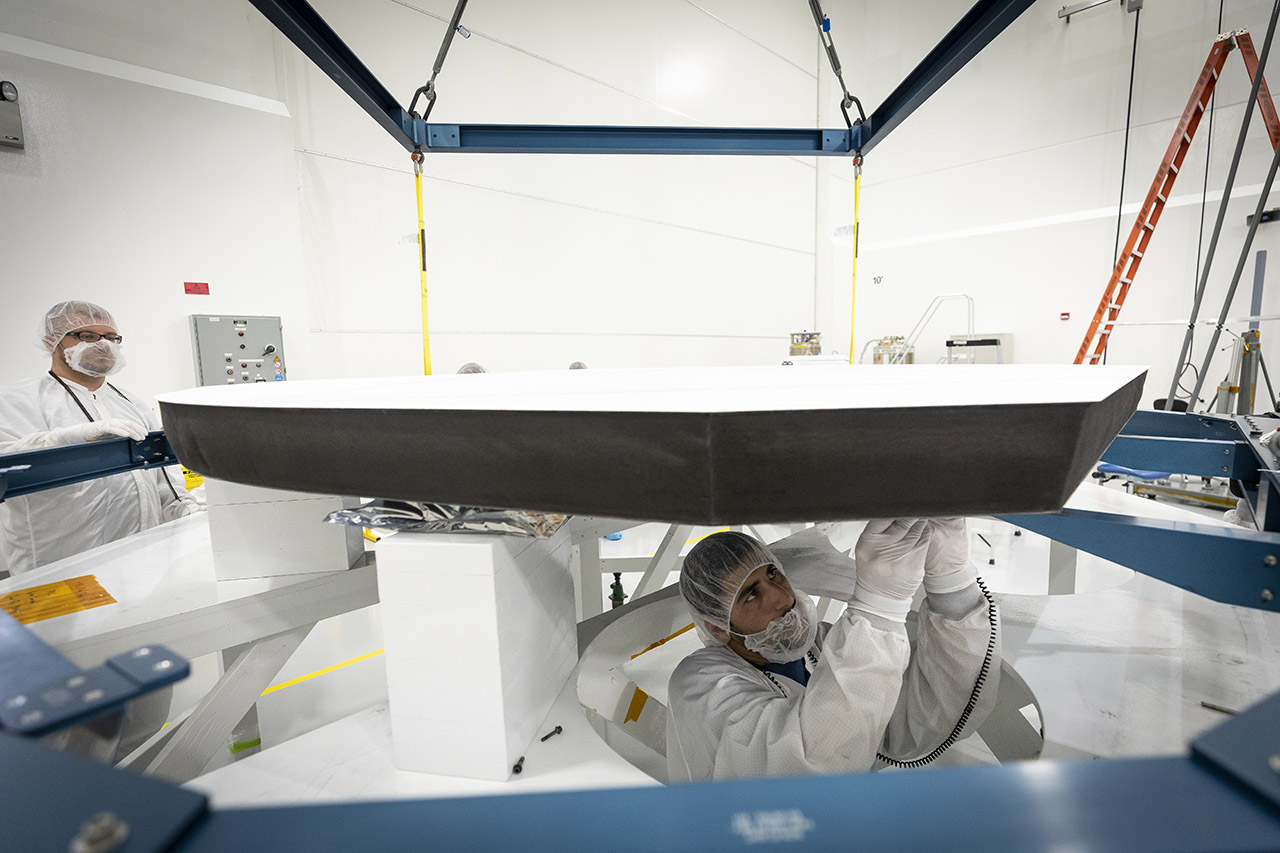

According to NASA officials, engineers added a heat shield eight feet in diameter to the Parker Solar Probe spacecraft on June 27 to keep the instruments at the "relatively comfortable temperature" of 85 degrees Fahrenheit (29.4 degrees Celsius). The mission is scheduled to launch in August 2018.

The Parker Solar Probe's goal is to explore how the sun directly affects life on Earth, according to NASA officials. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory designed, built and and manages the mission, and will also operate it. Parker Solar Probe is part of NASA's Living with a Star Program, which is managed for the Heliophysics Division of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C., according to the agency.

No human-made object has ever gone as close to the sun as this mission plans to go, and if the Parker Solar Probe succeeds, it will travel to within 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometers) of the sun's blazing surface, where temperatures reach 2,500 degrees F (1,371 degrees C), NASA officials said in the statement.

The probe's heat shield is called the Thermal Protection System. NASA officials said that it's made of a 4.5-inch-thick carbon foam core that is 97 percent air and extremely lightweight. It sits between two panels of superheated carbon-carbon composite. And the side of the heat shield that will face the sun is sprayed with a special coating to reflect the star's energy away from the spacecraft.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And there's a good reason the heat shield must be lightweight: "Because Parker Solar Probe travels so fast — 430,000 miles per hour [692,018 km/h per hour] at its closest approach to the sun, fast enough to travel from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., in about 1 second — the shield and spacecraft have to be light to achieve the needed orbit," NASA officials said in the statement.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.