Happy Anniversary, Viking 1! What Early Landers Taught Us About Mars

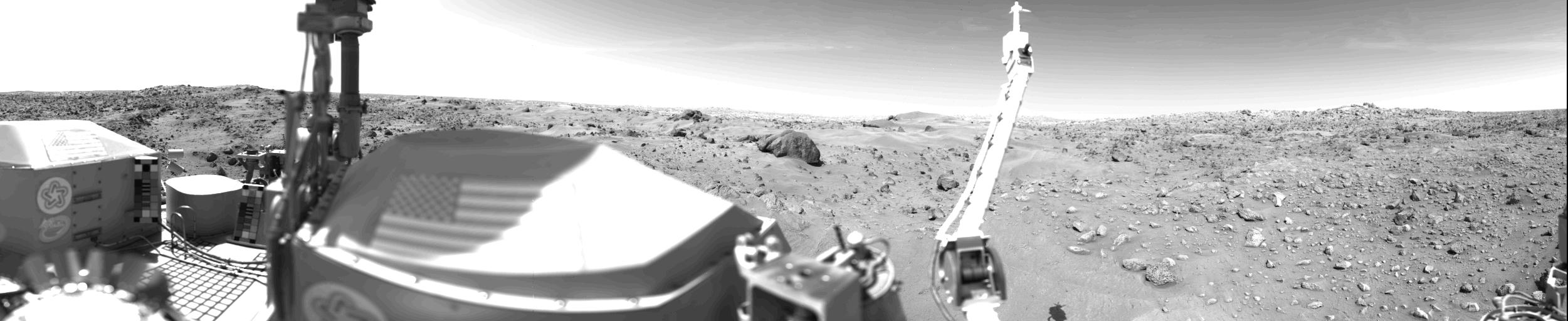

You may know that humanity first set foot on the moon 49 years ago today. But July 20 looms large in spaceflight history for another reason as well: It's the date, in 1976, when NASA's Viking 1 Mars lander pulled off the first American touchdown on the Red Planet.

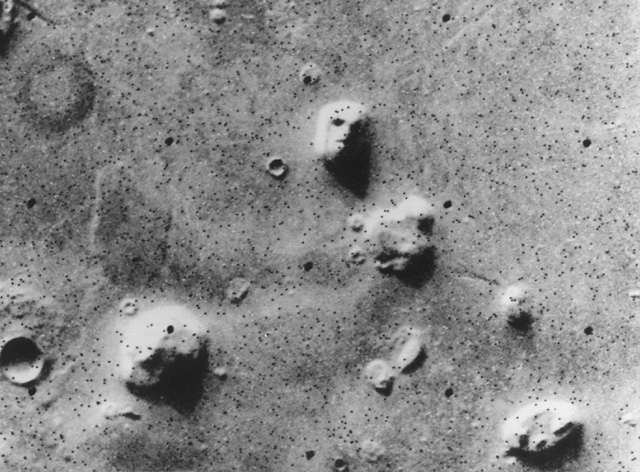

Viking 1 was just one piece of the larger Viking program, which launched two orbiters and two landers toward the Red Planet in 1975 to hunt for signs of life and gain a better understanding of the geological history of Mars.

Though Viking's technology and science work date back more than four decades, the early Mars program is still highly relevant today. For starters, scientists are still trying to understand what the landers' puzzling experimental results mean. And NASA's Curiosity rover recently found organic molecules — the carbon-containing building blocks of life — on Mars. [The Historic Viking 1 Mars Landing in Pictures]

The Vikings also carried seismometers and other equipment to help scientists learn more about the Martian interior, which makes these landers ancestors of NASA's InSight mission that will land on Mars this November.

Organic molecules and the search for life

Each of the Viking landers performed several life-detection experiments, which returned intriguing but ambiguous results. The robots also heated Martian soil samples in an oven and used a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (GCMS) instrument to look for any organic molecules boiling off.

Neither of Viking's GCMS instruments found any signs of organics, which was (and remains) quite surprising. Organics are common throughout the cosmos, including on asteroids and comets — which means meteorite impacts should deliver the molecules to the Martian surface on a fairly regular basis.

The Viking data remain a subject of study and debate to this day. For example, after a reanalysis, researchers recently determined that the landers detected chlorobenzene, an organic compound commonly used in herbicides and rubber. Chlorobenzene is not a sign of life, but it could be a byproduct of how the Vikings' ovens processed organic molecules on the surface when analyzing samples.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new research suggests that the chlorobenzene the landers found was created by a reaction between perchlorate, a salt common in the Martian soil, as well as indigenous Red Planet organic carbon. In other words, Viking might have found the building blocks of life on Mars some four decades ago. The researchers caution, however, that some of the instruments had potential organic contaminants, so it's not clear if the organics were indeed from Mars.

The recent study's lead author, Melissa Guzman, said that, given her interesting results — as well as the recent find of organic molecules by Curiosity — it's imperative to get life-detecting instruments to the Red Planet soon. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

"We haven't sent life-detection instruments to Mars since Viking sent its three biology experiments," Guzman, who's based at the University of Paris-Saclay in France, told Space.com via email.

"But Curiosity has done a fantastic job of further characterizing the habitability of Mars," she added. (The rover has beamed home data about ancient watery environments and current radiation conditions, among other things.)

Guzman pointed to an upcoming European rover from the ExoMars program that will leave Earth in July 2020. The rover will have an instrument called MOMA — the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer. MOMA is designed to search for organic molecules, focusing particularly on the "handedness" of life, which is called homochirality.

"We're in a very exciting time for astrobiology, because there is momentum to send life-detection instruments both to Mars and to some of the icy satellites — like [Saturn's] Enceladus and [Jupiter's] Europa — around the gas giants who have shown promise of habitability for life," Guzman said.

NASA is planning to launch a life-detection rover of its own in 2020. The Mars 2020 rover will search for signs of ancient life and cache promising samples for future return to Earth, among other duties.

Probing Mars' interior

The two Viking landers had seismometers on them that were added at the last minute (relatively speaking) in the mission design, according to InSight principal investigator Bruce Banerdt, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"They had a little bit of extra payload mass capability left over," Banerdt told Space.com.

"But it was the poor stepchild of the payloads, so to speak," he added. "It got the last crumbs of the power allocation and data allocation."

The seismometer also was bolted to the top of the spacecraft, which some engineers thought might still be OK for looking for "marsquakes." Unfortunately, wind noise swamped Viking 2's seismometer, and a cable problem disabled the seismometer on Viking 1.

"That was a real disappointment for everyone," Banerdt said. "I was a summer intern at JPL doing the Viking landing; that was my favorite instrument, but I wasn't involved in it."

Fortunately, the InSight lander — whose name is short for "Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport" — will carry a seismometer of its own that will be placed directly on the Red Planet's surface. The instrument will detect meteor strikes and marsquakes, and its data will allow scientists to deduce some key properties of the Red Planet's interior, mission team members have said. [Mars InSight: NASA's Mission to Probe Red Planet's Core (Gallery)]

A less-famous experiment of Viking was a radio-science investigation that tracked the "wobble" of the Martian north pole, which points in different directions over a 165,000-year cycle. A follow-up investigation was performed by NASA's Pathfinder lander in 1997, and InSight will do similar work after it lands on Mars, Banerdt said. InSight's radio-science experiment will be so sensitive that it can even track a separate wobble of the north pole during a Martian year.

"There's a little wobble that happens on the scale of months, and that's mostly because of the sloshing around of the liquid in the Martian interior," Banerdt explained. "As it sloshes around, it interacts with the rocky mantle above it and causes the rocky planet to wobble a bit."

This wobble is also present on Earth, where it is called the Chandler wobble. Analyzing the wobble can enable researchers to gauge the density of a rocky planet's interior and the size of its core, Banerdt said.

Knowing the size and composition of the core also relates back to a planet's habitability, he said, because it is in the core that a planet generates its magnetic field. A global magnetic field protects a planet's atmosphere by deflecting charged solar particles; when Mars lost its field about 4 billion years ago, such particles began stripping away the planet's once-thick air, eventually causing the world to shift from relatively warm and wet to cold and dry.

"Looking at the history of the core itself is related back to the possible history of habitability," Banerdt said.

The motions of the Viking orbiters (as well as many other spacecraft circling Mars) also gave some information about the interior, Banerdt said. The subtle dips and jumps in the probes' orbits allowed scientists to map out the gravity variations on Mars, which, in turn, reveal what kinds of rocks — for example, dense volcanic rocks or lighter sedimentary ones — are in different areas. Such data also helps researchers map changes in the thickness of the Martian crust from place to place.

"It's kind of a blurry telescope into the interior," Banerdt said. "We have used it to infer things about the evolution of the crust."

The InSight lander, which launched in early May, has had a "flawless" cruise so far, he added, and most of the payloads have been checked out in flight already. The team also took some pictures of the inside of the aeroshell that encloses the spacecraft, and to their surprise, they were able to see a bit of the thermal blanketing on the inside of the spacecraft. Those pictures will be released soon, Banerdt said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.