The handlers of NASA's New Horizons spacecraft are gearing up for one last shadow-chasing adventure.

On Saturday (Aug. 4), the tiny, far-flung object 2014 MU69 will pass in front of (or "occult") a distant star, casting a dim shadow on two slivers of Earth in Senegal and Colombia. New Horizons team members will be ready, camped out in those slivers with their telescopes.

The goal is to learn as much as possible about 2014 MU69, nicknamed Ultima Thule, which New Horizons will zoom past on Jan. 1, 2019. [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

"This occultation will give us hints about what to expect at Ultima Thule and help us refine our flyby plans," New Horizons occultation-event leader Marc Buie, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement.

This is not the mission team's first shadow rodeo. Last summer, scientists traveled to Argentina and South Africa for occultation observations; the Argentina crew hit the jackpot, gathering data that helped set the planned flyby distance at 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers).

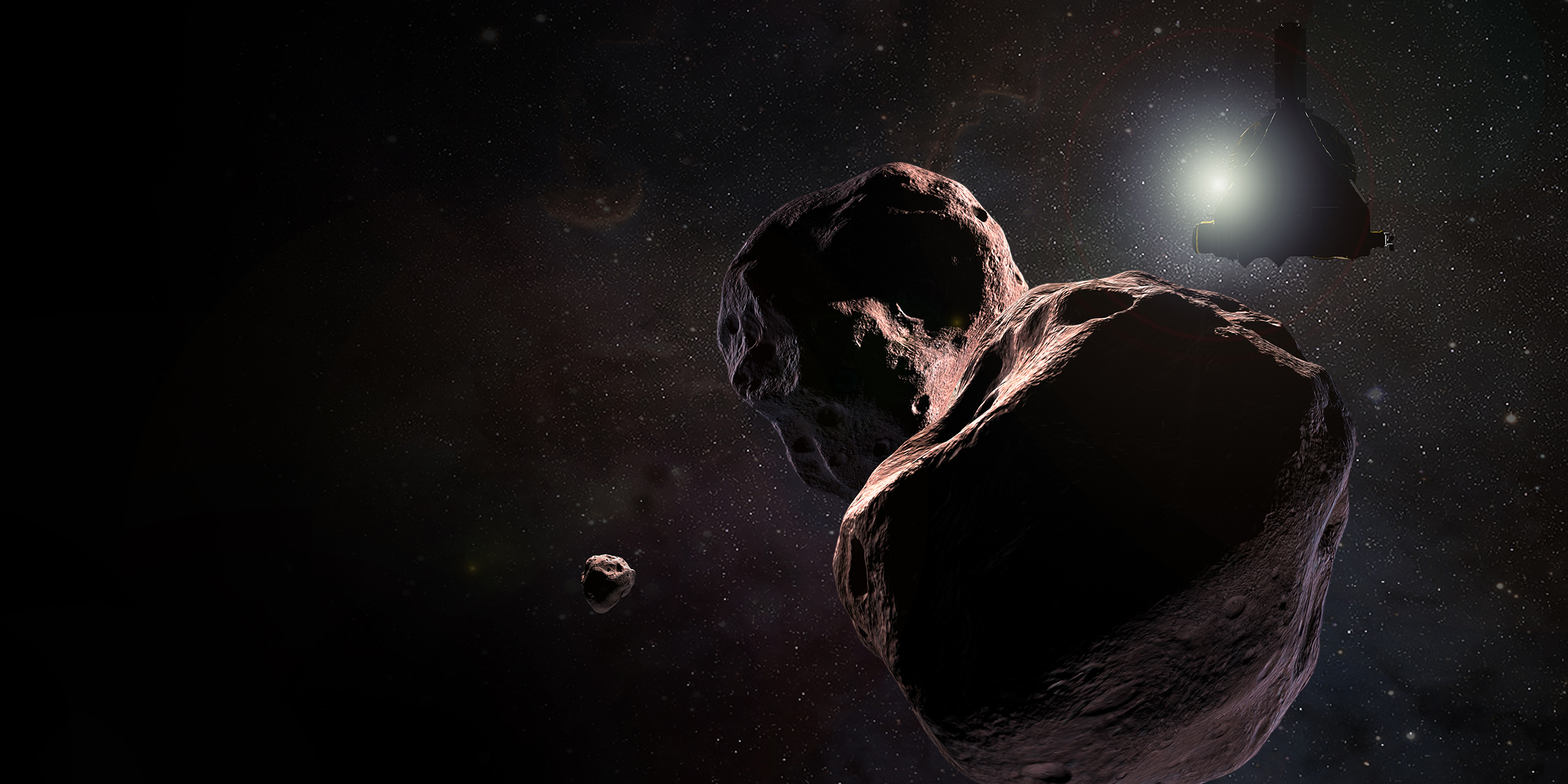

Last year's observations also suggested that Ultima Thule may actually be two co-orbiting objects, and that it might even have a moon.

There are no occultation-observation plans beyond this weekend's campaign, mission team members said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ultima Thule lies about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto, which New Horizons famously flew by in July 2015. Scientists think Ultima Thule is about 20 miles (32 km) across if it's a single object; if it's two bodies, each component is probably 9 miles to 12 miles (15 to 21 km) long.

The object's small size and extreme distance from Earth explain why occultations are so prized: It takes a special set of circumstances to get any kind of a look at Ultima Thule, even an indirect one.

"Gathering occultation data is an incredibly difficult task," Buie said. "We are literally at the limit of what we can detect with Hubble, and the amount of computer processing needed to resolve the data is staggering."

The Ultima Thule encounter is the centerpiece of New Horizons' extended mission. The upcoming flyby will provide an up-close look at a frigid relic from the solar system's early days and help astronomers better understand the diversity and complexity of the Kuiper Belt, the distant realm beyond Neptune's orbit. Buie was referring to the Hubble Space Telescope, whose observations — along with those of the European Space Agency's Gaia spacecraft — allowed the New Horizons team to pinpoint the Senegal and Colombia shadow slivers.

The Kuiper Belt includes the 1,477-mile-wide (2,377 km) Pluto, which is a very different object than Ultima Thule.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.