How NASA's New Solar Probe Will 'Touch' the Sun on Historic Mission

We see it every day, but our sun still poses countless mysteries.

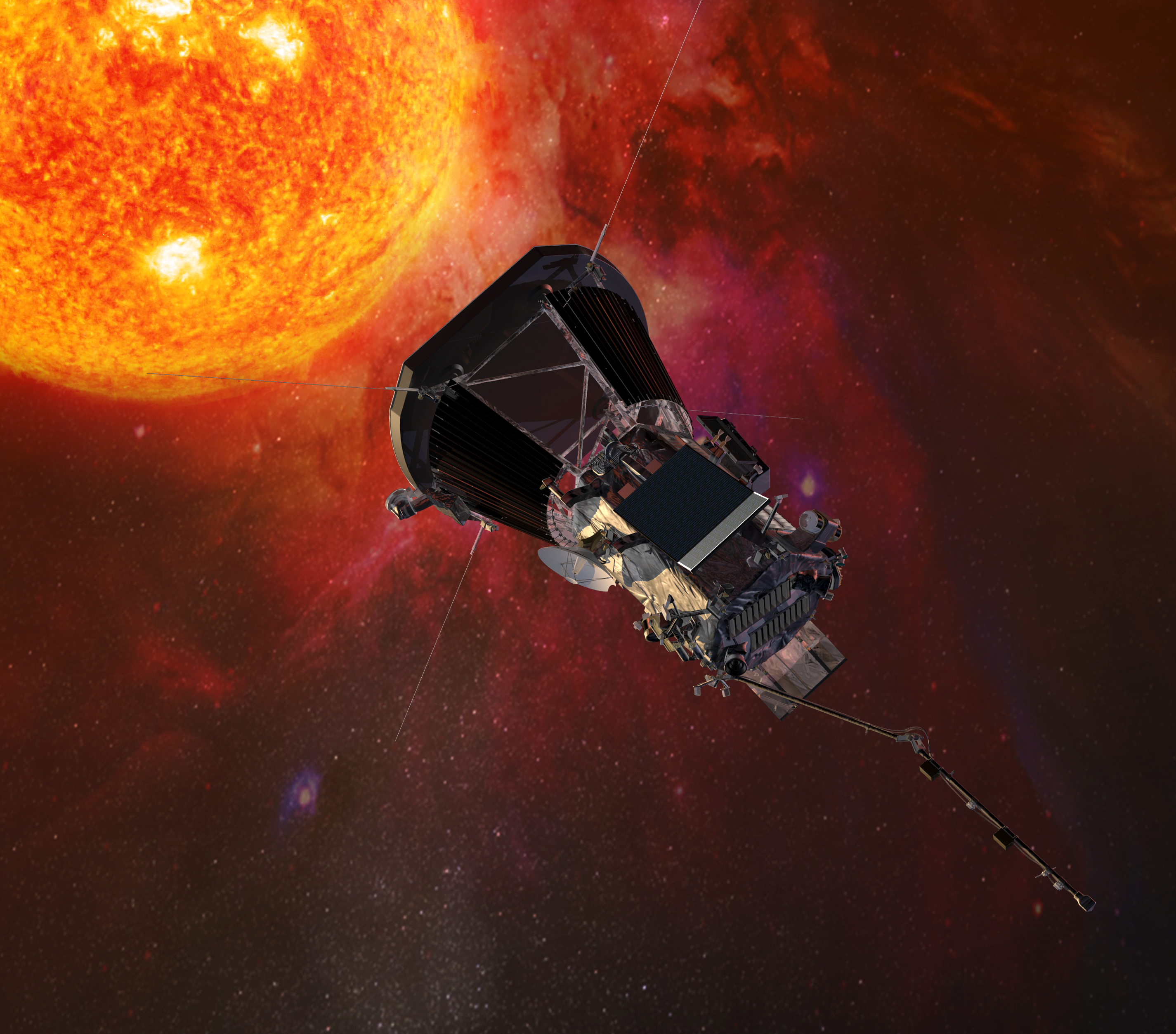

On Saturday (Aug. 11), that will begin to change, as NASA launches its Parker Solar Probe, the first mission ever to get up close and personal with our star. At its closest approach, the spacecraft will fly less than 4 million miles (6 million kilometers) above the surface of the sun, directly through its blazing-hot atmosphere.

"She's a plucky little spacecraft," project scientist Nicola Fox, a solar scientist at Johns Hopkins University, told Space.com. "She's going to the last major region of our solar system to be explored." [How NASA's Parker Solar Probe Will Keep Its Cool at the Sunl]

Plenty of spacecraft have studied the sun, of course, but none have had the potential of the new mission: neither its orbital path nor its instruments have been possible until now, despite 60 years of scientists' dreams. "I think the Parker Solar Probe is a fascinating mission. I think it's got something for everybody," Fox said.

The entire project cost $1.5 billion and the mission will continue until 2025. The Parker Solar Probe may not look like much: It's about 10 feet (3 meters) tall and more than 3 feet (1 m) across. Most of its instruments hide behind a giant heat shield that's almost 8 feet (2.3 m) across and 4.5 inches (11.43 centimeters) thick.

That heat shield is what takes a seven-year mission to the sun out of science fiction and makes it a reality. The shield will keep the temperature-sensitive instruments on board the spacecraft at a comfortable 85 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius).

Those instruments tackle four different questions about the sun. First, there's a high-tech camera called the Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe, which will capture photographs of what the spacecraft is about to fly through. That will let scientists match up the data other instruments collect with a visual image of solar phenomena like flares.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another instrument, called FIELDS, measures and maps electric and magnetic fields within the solar atmosphere, helping scientists understand how those forces interact with the highly charged particles called plasma that make up the sun and speed out to space in what scientists call the solar wind.

And two sets of instruments study those solar-wind particles. One set, called the Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons, will scoop up particles to measure characteristics like their speed and temperature. A second set, called Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun, will figure out how those particles got to be moving so fast — more than 1 million miles per hour (500 km per second) — in the first place.

That solar wind is one of the key scientific targets of the Parker Solar Probe, since it's a critical force shaping our entire solar system — and everywhere humans are likely to visit in the near future. (The official boundary of our neighborhood is in fact defined by how far the solar wind travels.)

The solar wind, as well as other stellar hiccups like the giant outbursts of plasma that scientists call solar flares and coronal mass ejections, cause a range of phenomena dubbed space weather.

Space weather includes the beautiful, harmless auroras that paint the northern and southern sky, but not every type of space weather is so benign. Space weather can also interfere with communications and navigation satellites orbiting Earth — and particularly powerful events can harm terrestrial power grids.[Parker Solar Probe vs. Blowtorch: Who Wins?]

Scientists hope that the data collected by the Parker Solar Probe will help them better predict space weather, providing enough warning of events to allow these crucial systems to be buffered from harm. "We can now add solid physics to the models," Fox said. "Close in to the sun, what is driving the solar wind, what is causing it to have this major effect on the planet?"

Right now, the sun is pretty quiet, nearing the minimum-activity level of its 11-year cycle. But in a few years, that will change, with the sun's activity picking up speed again. And the team behind the Parker Solar Probe hopes our star will show off its full range of moods, from tranquil to temperamental. The more different dynamics the probe can watch, the more scientists can learn about how our star really works.

"We're very lucky that it's a seven-year mission," Fox said. "We want to see all the different things that the sun throws at us."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.