Making the Most of the 2018 Perseid Meteor Shower Using Mobile Apps

This weekend brings us one of 2018's best astronomical events: the Perseid meteor shower. The Perseids are one of the most rewarding showers of the year, frequently delivering bright fireballs exhibiting long, persistent trails. While the shower recurs every year around this time, moonlight can spoil the fun. But for 2018, the moon will be in its new phase during the peak of the shower — leaving our night skies dark for meteor-seeking skywatchers. And ad bonus is that the peak occurs on a warm summer weekend!

Finding the ideal viewing location and knowing where and when to look will increase the number of meteors you see. In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll focus on how to use your mobile app to plan your observing session, offer tips for seeing the most meteors, and point out some special features to look for. [Perseid Meteor Shower 2018: When, Where & How to See It]

You can also watch the Perseid meteor shower live online here at Space.com on Aug. 12 starting at 5 p.m. EDT (2100 GMT), courtesy of the online observatory Slooh.com.

Meteor shower basics

Many people use the phrase "shooting star" to describe a meteor, but that's misleading. Meteors are happening right here at home, above Earth's surface, and are independent of the distant background stars. The light we see streaking across the sky is occurring within Earth's atmosphere.

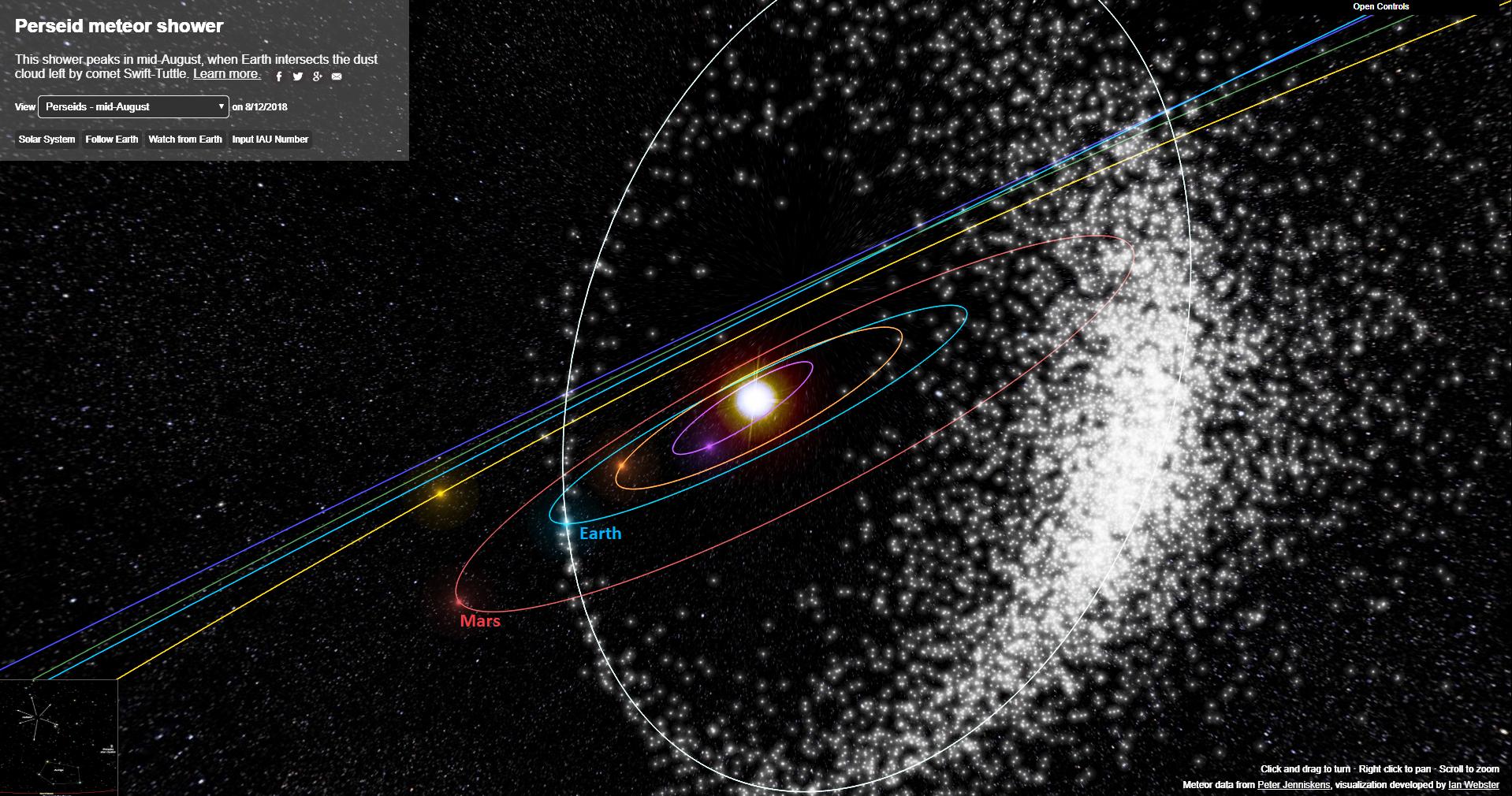

Meteor showers occur when Earth's orbit carries us through zones of debris left in interplanetary space by periodic comets (and, in some cases, asteroids). Over centuries, the pparticles, which weigh about 1 to 2 grams and range in size from sand grains to small pebbles, accumulate and spread out into an elongated "cloud" along the comet's orbit. (A good analogy is the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets quite dirty if the truck drives the same route many times!) If Earth's orbit intersects the comet's orbit, we experience a meteor shower that repeats annually because Earth returns to the same location in space on the same dates every year.

As we traverse the debris, our planet's gravity attracts the particles, and they burn up as "shooting stars" while falling through Earth's atmosphere. The particles enter the atmosphere at speeds ranging from 25,000 to 160,000 mph (40,000 to 256,000 km/h). And each particle's kinetic energy hionizes the air molecules it encounters, leaving a long trail of glowing gas that is less than a few feet wide, but many miles long. Most trails occur in the thermosphere, the region of the atmosphere about 50 to 75 miles (80 and 120 km) above the ground. Slower meteors need to reach the denser atmosphere at lower altitudes before forming a trail. Viewed from the Earth's surface on a clear, dark night, we see the trails glowing briefly as they streak in front of distant stars.

The colors that meteor watchers see come from a combination of factors. Red light is emitted by the glowing air molecules. The meteor itself is also burning up during its high-speed passage, and oranges, yellows, blues, greens and violets are produced when minerals in the particles — such as sodium, iron and magnesium — are vaporized. Scientists can analyze the color spectrum in a meteor trail and determine the particle's composition. If anything survives to land on the ground, it becomes a meteorite. An easy way to remember the difference is to recall that many rock names end with "-ite," like granite.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the debris zone — that is, how many days or hours it takes Earth to pass through it. A meteor shower commences on the date when the Earth first enters the debris zone. The shower then builds to a peak when Earth passes through the densest portion of the cloud, and then tapers off, ending on the date when the planet exits the zone.

The number of meteors produced during a shower depends on whether Earth passes through the densest region of the zone, or merely skirts the edges. Since that debris is also orbiting the sun, the density of the particles varies on a time scale that is related to the source comet's orbital period and shaped by the pull of other planets; producing years when more, or less, material is encountered. Planetary scientists create models of the debris distribution to help predict the intensity of showers each year. Apps designed for observing meteor showers take those variations into account.

The brightness of a shower's meteors is dictated by the average size of the grains in the zone. Some showers are known for having fewer, but brighter meteors, while others are dimmer, but much more prolific. Most showers are global events, but certain showers are better for observers in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere due to Earth riding high or low through the cloud. [How to See the Best Meteor Showers of 2018]

During a shower, meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but they will all be traveling away from a particular locationy, called the radiant, that lies within the constellation that gives the shower its name; in this case, Perseus for the Perseids. The radiant simply marks the direction in the sky that Earth is heading toward while the planet is traversing the debris zone. (This direction-of-travel rule can be broken when two showers are underway at the same time, with two different radiants, and by random meteors, called sporadics, which aren't part of the main debris field, but are isolated particles drifting in interplanetary space.)

Several factors affect how many meteors you will see during a shower. If Earth happens to traverse the densest part of the cloud while it's daytime, you'll be looking for meteors the night before or after the peak, somewhat reducing the numbers.

Because most meteors are dim, a dark sky is essential to see them. Unfortunately, the moon can ruin an otherwise terrific show. The new-moon phase, when the moon is near the sun, will leave the night sky dark. First-quarter moons set in early evening, and last-quarter moons don't rise until the wee hours, so meteor hunters can work around them. Full moons stay up all night and can spoil a shower. Thankfully, phases of the moon vary year from year, so every shower gets good years and bad. (Last year, the moon was just past full on the Perseids' peak night.) Your astronomy app will tell you the phase of the moon at the peak of a meteor shower. Look at all the dates around the peak to find nights when the moon is less of a factor.

How and when to see Perseid meteors

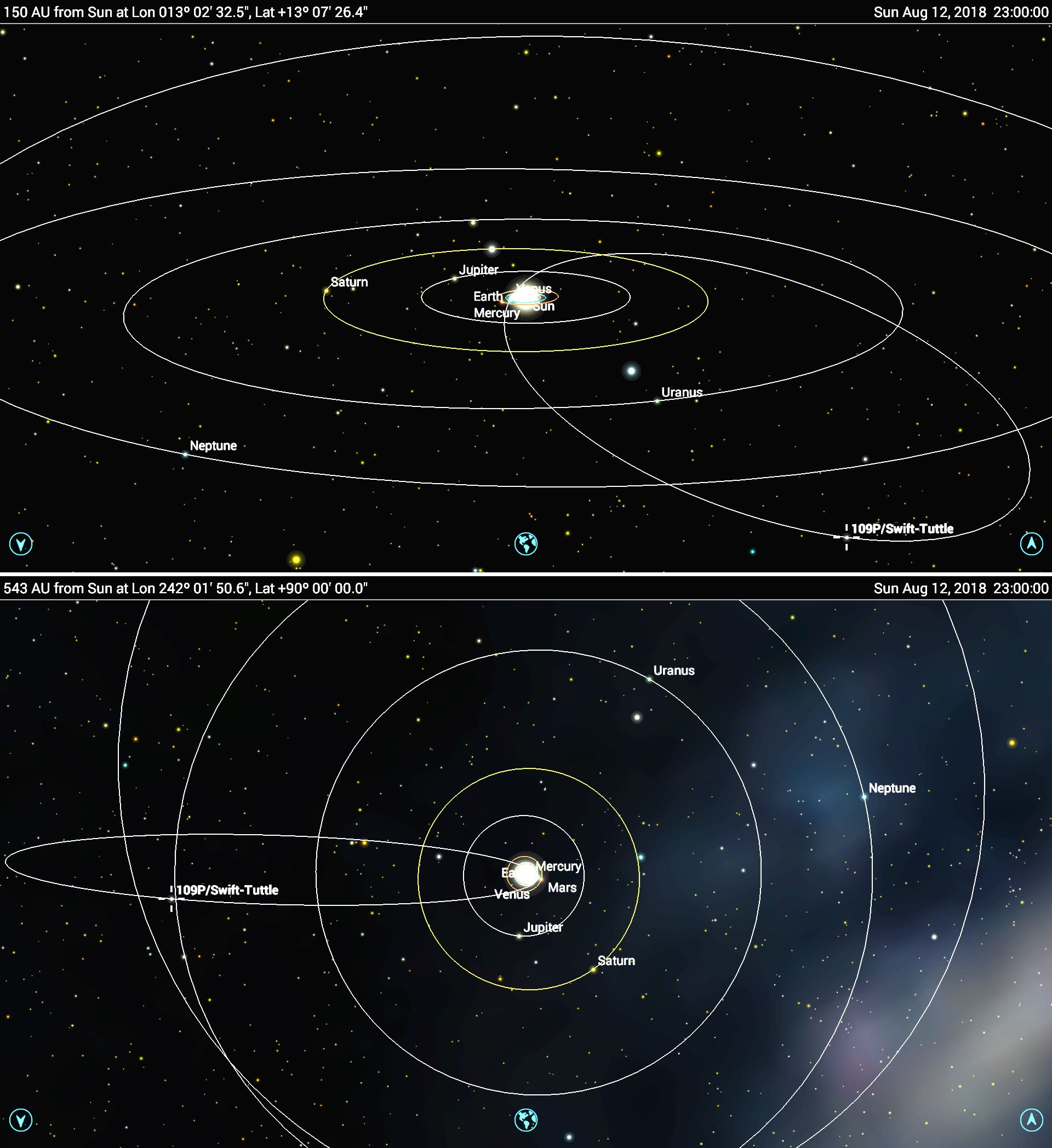

The source of the Perseid meteor shower is a 133-year periodic comet named Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. You can use the SkySafari app to see the comet's orbit rendered in 3D. Select the sun and tap the Orbit icon. The app will display a 3D model of the solar system. If the planets' orbits are not plotted, enable them in the Settings / Solar System menu. In the same menu, enable the Selected Object Orbit option. Now use the search menu and type "109P." When that comet's information screen appears, tap the Center icon. You can enlarge and rotate the view to see how the comet passes through the inner solar system and adjust the years to watch how the comet moves over time.

The highest number of Perseid meteors is expected from Sunday night through Monday morning (Aug. 12 to 13), when Earth will be closest to the core of the debris zone. The active period for this shower runs from July 13 through Aug. 26, so keep an eye out for Perseids before and after this peak weekend, too.

This shower is known for producing 60 to 80 meteors per hour, or more, at the peak — many manifesting as bright, sputtering fireballs with long, persistent trails. Watch for trails that linger for a few minutes while dissipating, like jet contrails!

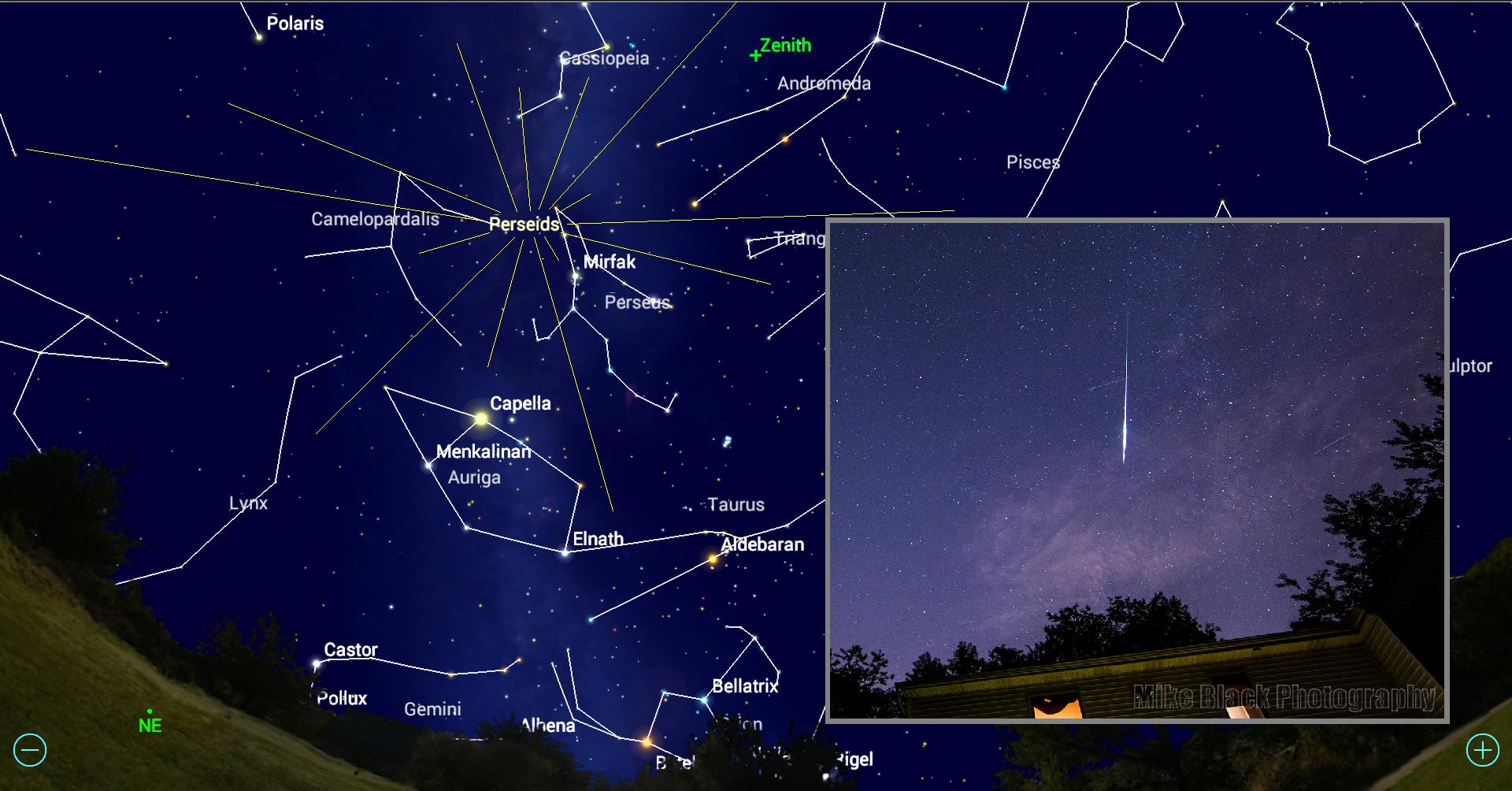

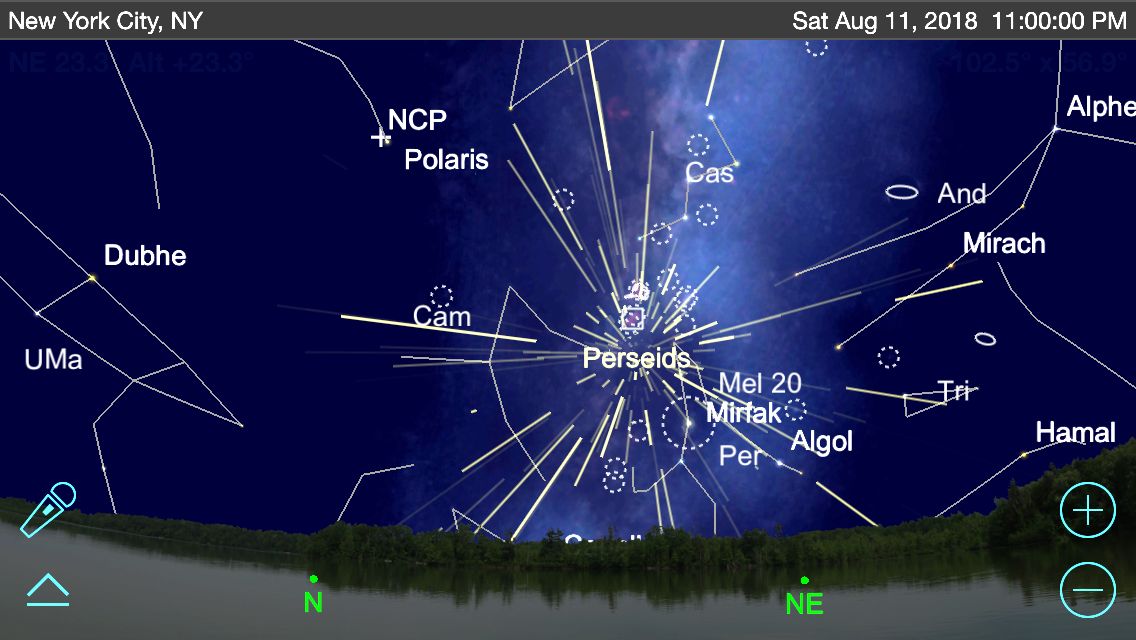

The Perseid shower's radiant lies between the constellations Camelopardalis the giraffe and Perseus the hero, but the meteors can streak across any part of the sky. The radiant is low in the northeastern sky during mid-August evenings, and nearly overhead by dawn. Meteor showers are best observed in the dark skies before dawn because that's when the sky overhead is leading the Earth as it plows directly into the oncoming debris field, like a moving car's windshield getting splattered with bugsd. And when the radiant is overhead, around 4 a.m. local time, the entire sky is available for meteors that are no longer hidden from view by Earth's horizon. When observing a meteor shower, don't focus your attention on the radiant. Meteors from that location will be heading directly toward you and will have very short trails.

For best results, try to find a safe and dark viewing location with as much open sky as possible. Even a 30-minute drive to a park or a rural site away from ncity lights will help a lot. You can start watching as soon as it is dark to catch the very long meteors that are produced by particles skimming the Earth's upper atmosphere. These are rarer, but they feature longer trains.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise lounge (or something similar) to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even when chatting with friends or family — they'll understand. And call out when you see a meteor; a bit of friendly competition is fun! If folks nearby don't mind, use your mobile device to add a musical accompaniment.

Meteor showers are a screen-free activity. But before you put your phone away, use the SkySafari app to find out where the radiant is. Use the list of Meteor Showers in the Search menu or type the name "Perseid" into the search bar. On the shower's information screen, tap the Center icon and then enable the app's Compass mode (in the toolbar). Then hold your device up and pan around until you find the constellation Perseus. The distinctive "W" of Cassiopeia will be above it.

Once you are ready to look for meteors, try to avoid looking at your phone or tablet — the bright screen will spoil your adaptation to the dark. If you must look, minimize the brightness or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will also reduce the chances of unexpected bright light. And remember that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors because they have fields of view that are too narrow.

Meteor showers are excellent opportunities to take wide-field, long-exposure images of the sky. Mount your camera on a tripod and take a series of exposures a few tens of seconds long. Or use a simple equatorial tracking mount to avoid star trails. See NASA's tips for photographing a meteor shower for more information.

Going beyond

SkySafari 6 and similar sky-charting apps will allow you to search for other meteor showers by name and will display their radiant location on the sky. The app will provide information about the source comet or asteroid; the start, end and peak dates; and some history. You can adjust the app's time to visualize when the radiant will be above the horizon for your location.

If you snap an awesome photo of Perseid meteors that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a potential story or gallery, send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.