NASA's Parker Solar Probe Is Headed to the Sun. So, What's Next?

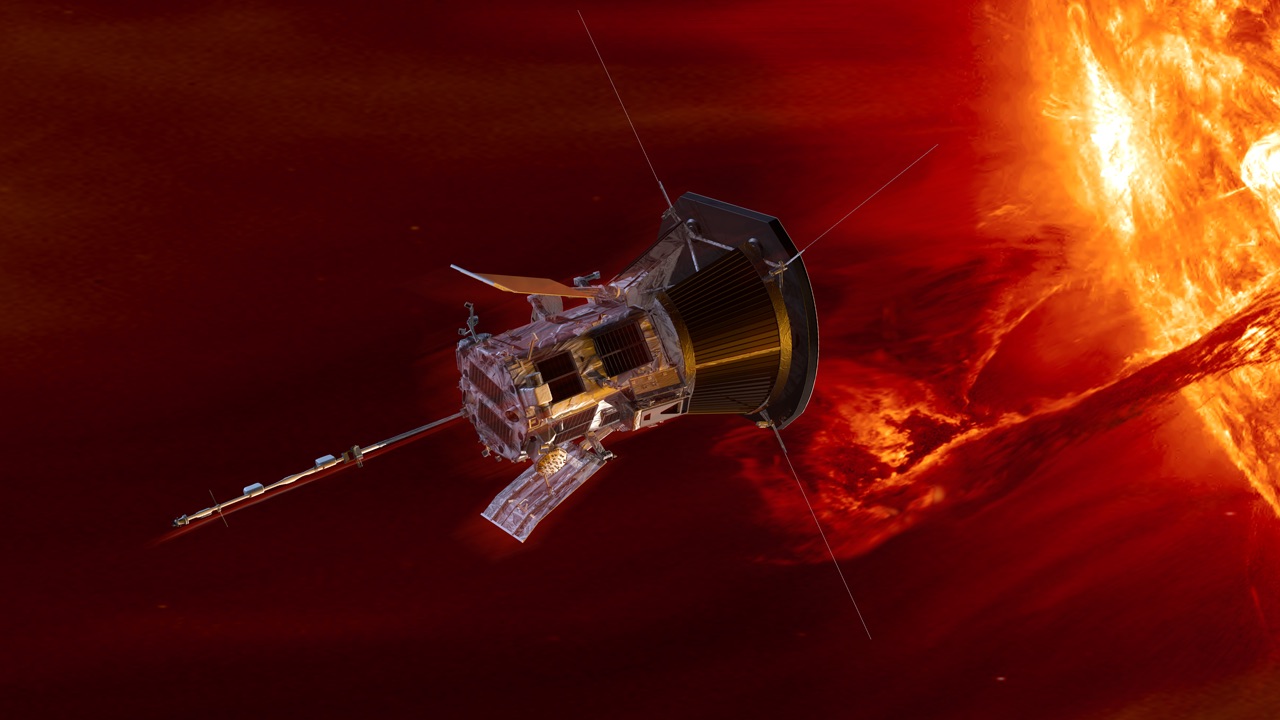

After decades of scientific brainstorming and years of construction, NASA's Parker Solar Probe is safely on its way to flying seven times closer to the sun than any mission has before.

Now that the spacecraft is finally off the ground, it won't be long before scientists can start digging into its data — and that data will keep coming for seven years.

"There's definitely a coiled-spring feeling," project scientist Nicola Fox, a solar scientist at Johns Hopkins University, told Space.com earlier this week, before the launch. "We're just ready for her to leave this planet." [The Greatest Missions to the Sun]

And now, the spacecraft has finally left Earth. Here's where the journey will take it.

Here comes the sun

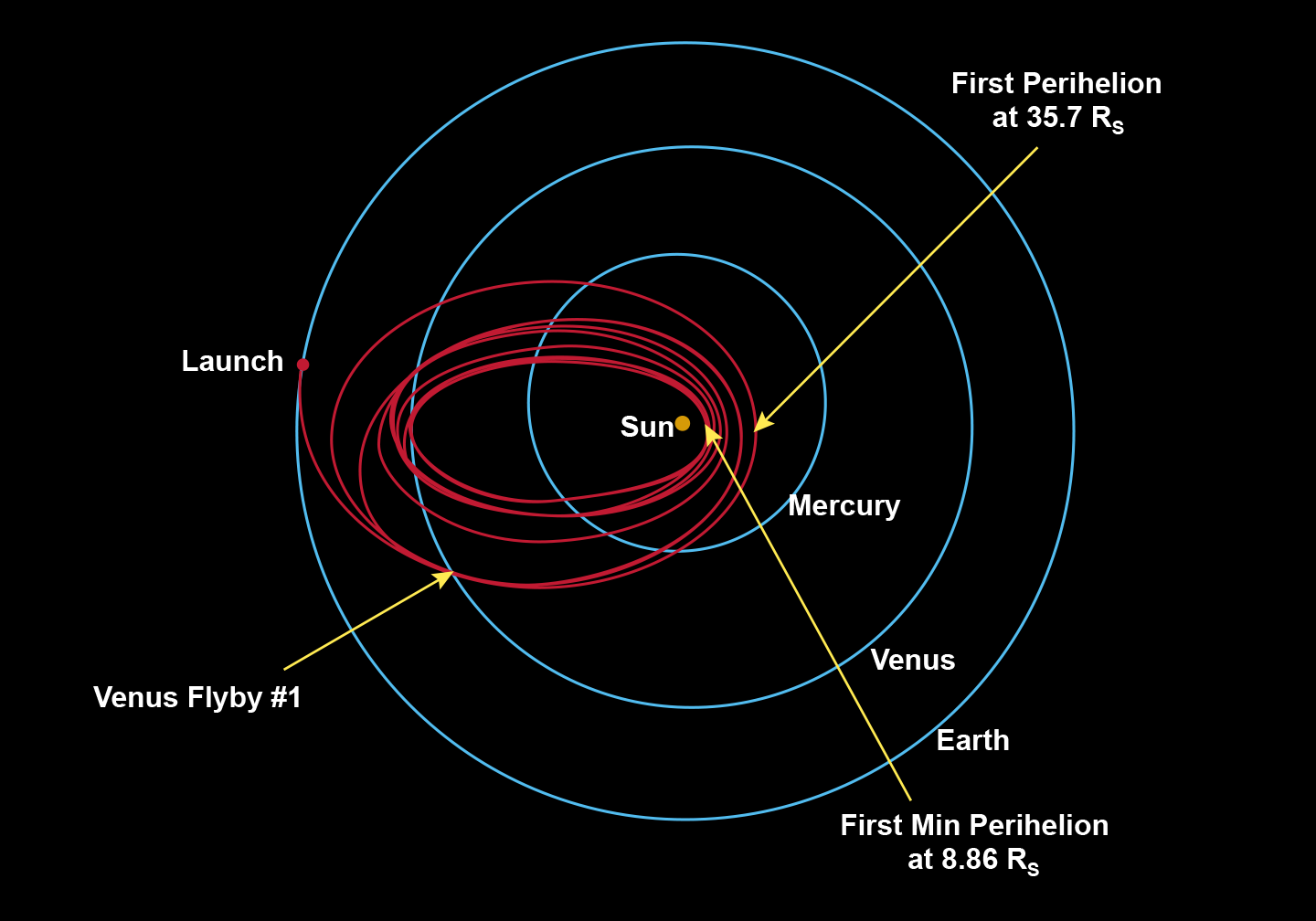

The $1.5 billion Parker Solar Probe needed a ton of speed to escape Earth's orbit, hence the total of three rocket stages that fired during the launch. That will carry it to the neighborhood of Venus in just six weeks, arriving by late September.

On Sept. 28, the spacecraft will need to pull off a careful maneuver designed to gently slow it down and begin its calculated dance with the sun. That maneuver, called a gravity assist, will pass a little of the spacecraft's acceleration to the planet and edge the probe a little closer to the sun.

The Parker Solar Probe will then begin its first of 24 orbits around the sun, with its first close approach, or perihelion, coming on Nov. 1.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Each orbit will be petal-shaped, skimming over the sun closely and then flying out farther into space to close out the orbit. The bulk of the probe's science work will come when it is within a quarter of the distance between Earth and the sun — although the team is hoping that the instruments can be turned on for as much of the mission as possible.

The early orbits, while remaining farther away from the sun, will be special because the spacecraft will spend its time close to the sun in essentially the equivalent of geosynchronous orbit, hovering over the same region. "Not a lot of people appreciate how entertaining these periods are going to be," Justin Kasper, a physicist at the University of Michigan and principal investigator for one of the probe's instruments, told Space.com about these early orbits.

During these periods, which scientists call fast radial scans, the spacecraft will swoop in at a speed that closely matches the sun's speed of rotation, and then swoop out again. While the spacecraft keeps pace with the sun's rotation, it will be able to watch how the same region of the sun behaves over a period of about 10 days.

"We're really able to hover and stare at it," Fox said, giving the team "the ability to spend days looking at the dynamics of how one region of the sun is changing — or maybe it isn't changing."

That means there's plenty of science to look forward to years before the spacecraft completes its closest approach to the sun near the end of the mission. "It might take us five years to get to our closest orbit, but we should have some amazing insights into our sun just this winter," Kasper said. "We're going to have some amazing observations this November with that first perihelion." [What's Inside Our Sun? A Star Tour from the Inside Out]

Seven years to go

As the mission continues, the spacecraft will move closer and closer to the sun, eventually coming to less than 4 million miles (6 million kilometers) above the visible layer of the sun that we think of as the surface.

On each orbit, the spacecraft will take the same measurements at different depths in the sun's atmosphere, which is called the corona. That layer, which is invisible from Earth except during a total solar eclipse, reaches temperatures of millions of degrees (Fahrenheit or Celsius).

"It's all exactly the same observations; the beauty of the Parker Solar Probe mission is that we are getting [the same data from] these different locations," Fox said. "We really do get a chance to look at the dynamics in all different locations in the corona."

Scientists are hoping that will help them decipher how the corona gets so hot and how the sun produces phenomena like the solar wind and solar flares, which have serious impacts on space travel, satellites and even life here on Earth.

In addition to sampling different layers of the sun, the probe will catch our star displaying a complete range of activity, since it undergoes an 11-year cycle from relatively tranquil to particularly tempestuous conditions and back again.

"The sun is very different during those different phases," Fox said. "We do want to see a nice broad spectrum of solar activity.

Squeezing as much science in as possible

But while the Parker Solar Probe is gathering all that data, the spacecraft won't be able to communicate with Earth. Instead, it will focus on making as many observations as possible. Then, it will send back huge chunks of information in batches.

Several of those data dumps will come as the spacecraft executes another crucial chore: dancing around Venus to inch closer to the sun. The probe will repeat the gravity-assist maneuver planned for late September a total of seven times throughout the mission, until the spacecraft has slipped too close to the sun to be able to loop around Venus.

And if all goes well, scientists may get a bonus in addition to the wealth of solar data: observations of Venus. During the sixth gravity assist, the spacecraft won't be aligned well to send data home, so if it has enough power, it may leave its instruments on and turn them to its dance partner.

"There is an absolute dearth of Venus missions," Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University who studies the planet, told Space.com. "A single flyby in and of itself would not revolutionize our understanding of Venus, but it would be extremely useful."

Venus will need its own revolution — but our understanding of the star that shapes every day of our lives will never be the same after scientists start analyzing the data the Parker Solar Probe sends home.

End of the road

Of course, all good things must come to an end, and the Parker Solar Probe's mission is due to last until mid-2025. If the spacecraft still has fuel, which it uses to twist itself to keep delicate instruments hidden behind a protective heat shield, the scientists hope that the mission could, theoretically, be extended.

But sooner or later, that fuel will run out, and the spacecraft will be helpless, its high-tech heat shield rendered useless. The instruments and the probe's skeleton will slowly break apart until nothing is left except the heat shield itself, Parker Solar Probe project manager Andrew Driesman, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, said during a NASA news conference on Aug. 9.

"In hopefully a long, long period of time — 10, 20 years [whenever the spacecraft runs out of fuel and breaks apart] — there's going to be a carbon disk floating around the sun in its orbit," Driesman said. Then, he added, it's anyone's guess how long it could circle our sun as a lonely reminder that the star once fostered humans who developed the technology to reach out and touch it. "That carbon disk will be around until the end of the solar system," Driesman said.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.