Why We Can't Depend on Robots to Find Life on Mars

A Senate subcommittee asked for reasons to support sending humans to Mars, and, boy, did they get one from Ellen Stofan, NASA's former chief scientist.

Stofan, who now leads the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, argued that if we truly want to find and understand any potential traces of ancient life on the Red Planet, robots can't do it alone — we'll need humans on the ground.

"While I'm optimistic that life did evolve on Mars, I'm not optimistic that it got very complex, so we're talking about finding fossil microbes," Stofan told a Senate subcommittee devoted to science issues on Aug. 1, adding that those fossils would be incredibly hard to find. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

"That's why I do think it will take humans on the planet, breaking open a lot of rocks to try to actually find this evidence of past life," Stofan said. "And finding one sample is not good enough; you need multiple samples to understand the diversity."

NASA hasn't sent a robot designed to identify traces of life on Mars since the Viking missions in the 1970s. But with the soonest possible human Mars mission still a decade and a half away, is there any hope that robots could pinpoint ancient Martian life before humans get there?

Whether our life-hunting emissaries are mechanical or human, they'll be guided by what we've learned on Earth — and discovering ancient microbial life is already pretty tricky here, Frances Westall, an astrobiologist at the National Center for Scientific Research in France, told Space.com. Westall, who looks for traces of ancient microbial life on Earth, said, "That's still quite controversial, and that's having access to the most sophisticated laboratories on Earth." Right now, she said, that work always relies on a combination of on-site humans and distant labs — no robots involved.

Just as here on Earth, scientists are fighting some grim odds when it comes to hunting traces of Martian organisms that may have lived billions of years ago. "Of course, most things never fossilize; a few things do get preserved, typically those things that have hard parts," Sean McMahon, an astrobiologist at the University of Edinburgh in the U.K., told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But on one front, the search for ancient life on Mars has a leg up over its terrestrial equivalent, since Mars doesn't have phenomena like plate tectonics and volcanism constantly destroying its geological record, Tanja Bosak, a geobiologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Space.com. So if there was life on the Red Planet billions of years ago, its traces could well remain.

Robots versus humans

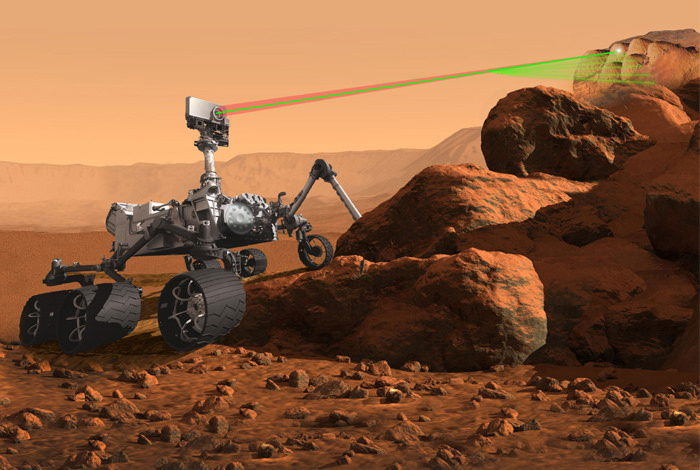

Mars has attracted eight successful landers and rovers over the years, with its highest-profile current resident being NASA's Curiosity rover. That mission was carefully designed to look for places where life might once have thrived — but not to look for traces of that life.

And it has done just that, identifying mudstones in Gale Crater as particularly promising and spotting ancient organic molecules not necessarily created by life. But robots aren't perfect, and there are still plenty of lingering questions about Martian geology, he added. "There are rocks that rovers have visited and imaged and analyzed and we're still arguing about what they are," McMahon said. [Ancient Mars Lakes & Laser Blasts: Curiosity Rover's 10 Biggest Moments in 1st 5 Years]

But robots are much hardier than humans. "The place where I would begin the conversation is where is it safe to land, and the robotic program has a demonstrated capability for landing in difficult terrain," Ken Farley, an astrobiologist at the California Institute of Technology and the principal investigator for NASA's next Mars rover, told Space.com, adding that robots can land closer to the rocks scientists want to look at. While humans are more mobile than robots, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin covered only about 90 yards (82 meters) during their moon landing.

Because Martian life likely never got larger than microbial, the features scientists are looking for are going to fit within a robot's view. But there are some ways humans still outpace robots, particularly when it comes to looking at the bigger picture of life on Mars. "Biologists, geologists and chemists on the ground could do more than identify evidence of past life on Mars," Stofan told the senators. "They could study its variation, complexity and relationship to life on Earth much more effectively than our robotic emissaries."

And Westall said that she doesn't think robots will ever match human geologists for their knowledge and instincts in the field, or their productivity. "I'm a geologist and I go into the field and I need to see things with my eyes, and if I had the chance I'd go to Mars," she said. "A human geologist can do in a week what the Mars rovers can do in a year."

Best of both worlds?

But there's a sort of compromise that may be even more productive than landing humans on Mars. The secret lies in sample-return missions, in which robots collect rocks for scientists to study in terrestrial labs. NASA and its Japanese counterpart each currently have missions at asteroids doing just that.

The sample-return format means scientists will have much more freedom to follow their curiosity, giving them the power to one day answer questions they don't yet know to ask, Farley said. He pointed to the investigation of the infamous Allan Hills 84001 Martian meteorite, in which one argument for it containing proof of fossilized life, since debunked, rested on the presence of small magnetic minerals. "You would never be able to make the measurements [on Mars] because you never would have dreamed of sending an instrument that could do that." [Top 10 Discoveries by Mars Rovers Spirit & Opportunity: A Scientist's View]

And, of course, there are all the constraints inherent in getting an instrument to Mars, Farley said — it has implications for an instrument's size, weight, power, sensitivity to radiation and more. Unless we build a stunningly advanced lab on Mars, we'll always need to bring those samples home to study in earnest, Bosak said. "It comes down to the lab, and not one lab — multiple labs, really, an entire program that's dedicated to analyzing samples in a clean way," she said.

That's much more plausible here on Earth, which is where NASA's next Mars mission, called the Mars 2020 rover and due to launch that year, enters the picture. It will mimic Curiosity's skeleton but is tailored to find traces of life, rather than just environments that may once have been suitable for it. And it will be selecting and stashing bits of intriguing Martian rocks in the hope that a future mission will come and retrieve them, bringing back about a pound (0.5 kilogram) of Mars rocks to terrestrial laboratories.

But right now, NASA isn't working on that future mission: Mars 2020 is its last Red Planet scheme, which the National Academies of Sciences decried in a report published Aug. 7. The Mars 2020 team is just carrying on with their own work, hoping that eventually, someone will fetch them their souvenirs.

Sure, humans are great at picking up trinkets during their travels, and if engineers have developed the capacity to bring humans back from Mars, they can certainly manage a few pounds of rock. So a crewed mission would likely carry the same benefits as a robotic sample-return mission.

But maybe the robots have earned this one. Every clue we have that Mars was once habitable and could still hide traces of that life comes from robots, not humans on the ground, and finding life may not be the best way to argue for a crewed mission.

"The value of human exploration is exploration," Bosak said. "You can't deny the appeal of that, but that is a separate issue from being able to find life on Mars."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.