Water Ice Confirmed on the Surface of the Moon for the 1st Time!

It's official: There's water ice on the surface of the moon.

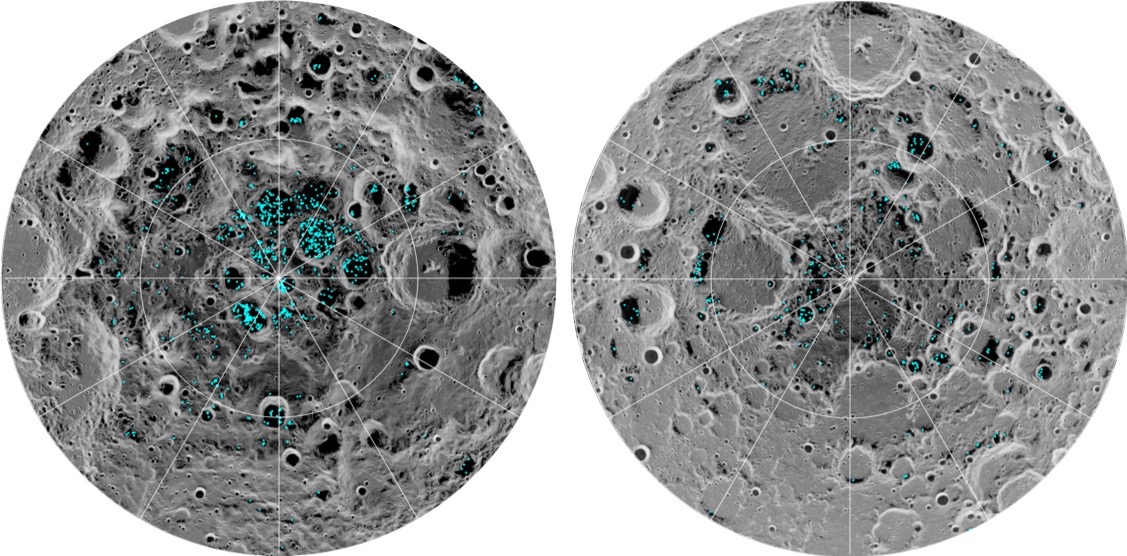

Researchers have confirmed the presence of the frozen stuff on the ground around the lunar north and south poles, a new study reports. That's good news for anyone eager to see humanity return to the moon for more than just a flag-planting mission.

"With enough ice sitting at the surface — within the top few millimeters — water would possibly be accessible as a resource for future expeditions to explore and even stay on the moon, and potentially easier to access than the water detected beneath the moon's surface," NASA officials wrote in a statement Monday (Aug. 20). [The Search for Water on the Moon in Pictures]

As that statement indicates, scientists already knew that the lunar underground isn't bone-dry. For example, in 2009, an impactor released by NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) blasted a bunch of water into space after slamming into a permanently shadowed region of Cabeus Crater, which lies near the moon's south pole.

But it wasn't clear from the LCROSS data where, exactly, that excavated ice originally lay — how much gray dirt once sat atop it. And, while several instruments have spotted tantalizing hints of exposed lunar ice over the years, these detections had remained unconfirmed until now.

"Previous observations indirectly found possible signs of surface ice at the lunar south pole, but these could have been explained by other phenomena, such as unusually reflective lunar soil," NASA officials wrote in the same statement.

Some of those observations were made by NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) instrument, which flew aboard India's Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft. The pioneering Chandrayaan-1 — India's first moon probe, and the first spacecraft to return compelling evidence of lunar water — studied Earth's nearest neighbor from orbit from November 2008 through August 2009.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the new study, a team led by Shuai Li of the University of Hawaii and Brown University took a fresh look at M3 data. They spotted a distinctive signature of water ice in the reflectance spectra gathered by the instrument. [Moon Base Visions: How to Build a Lunar Colony (Images)]

This signature is present at many of the coldest and darkest spots on the lunar surface, within 20 degrees of both poles. There are differences from hemisphere to hemisphere, however. Ice is more abundant in the south, where it's found principally at the bottoms of permanently shadowed craters; in the north, the stuff is more widely, and thinly, dispersed.

Several factors might be responsible for this relative paucity of ice. For one thing, the moon's axis of rotation may have shifted more frequently over the eons than those of Mercury and Ceres, potentially exposing polar crater floors to sunlight more often, the researchers said. And it's possible that meteorite impacts have disrupted the moon's supplies of surface and near-surface ice more dramatically.

The new study was published online Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.