Monster Black Hole 'Feeding Frenzy' Hides Hundreds of Galaxies in New Photo

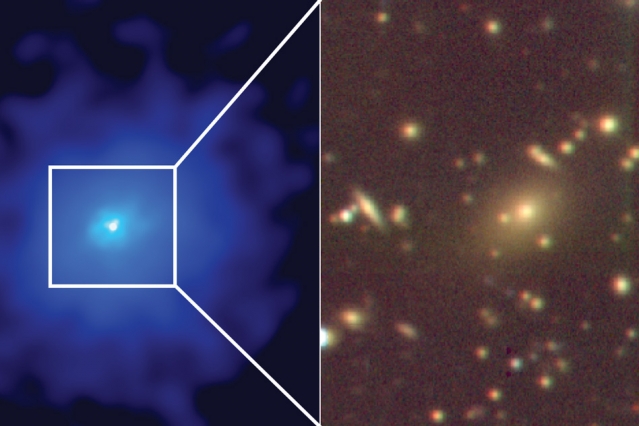

Scientists have found hundreds of galaxies hiding in plain sight, cloaked by the light emitted from an extremely active supermassive black hole. The galaxies and blazing black hole can be seen in a new image released by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The black hole, a type known as a quasar, sits 2.4 billion light-years from Earth and is so bright that astronomers have assumed it was alone in its area of space for decades, according to a statement from MIT. But as MIT researchers reported on Aug. 16 in the Astrophysical Journal, the quasar is actually at the center of a galaxy cluster. (Space.com reported on the study when it was first accepted to the journal and posted on ArXiv.org.)

A galaxy cluster is a collection of hundreds to thousands of galaxies bound together by gravity. Often, astronomers expect clusters to look "fluffy" and give off a very diffuse signal in the X-ray band, according to the statement. Quasars and black holes, however, tend to give off brighter, point-like signals. [Gigantic Galaxy Cluster Blazes in Amazing New Hubble Photo]

"The images are either all points, or fluffs, and the fluffs are these giant million-light-year balls of hot gas that we call clusters, and the points are black holes that are accreting gas and glowing as this gas spirals in," Michael McDonald, a physicist at MIT and co-author on the new work, said in the statement. The researchers theorize that the quasar at the center of this cluster is burning particularly brightly because it's on a "feeding frenzy." Huge chunks of matter are falling into the quasar from the disk of material surrounding it and causing the black hole to radiate large amounts of energy. The team estimates that the quasar is 46 billion times brighter than our sun.

The immense light produced by this feeding frenzy is responsible for hiding the galaxies surrounding the quasar, but researchers believe that the overshadowing is temporary. Eventually, they expect the black hole's radiance to fade and to start looking like they expect other cluster galaxies to look.

"This could be a blip that we just happened to see," McDonald said. "In a million years, this might look like a diffuse fuzzball."

McDonald and his team first discovered a hidden cluster in 2012, and the mystery as to why they initially missed it sparked a search for similar objects. "We started asking ourselves why we had not found it earlier, because it's very extreme in its properties and very bright," McDonald says. "It's because we had preconceived notions of what a cluster should look like. And this didn't conform to that, so we missed it."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In response, the scientists set up a survey called CHiPS (Clusters Hiding in Plain Sight) to re-examine X-ray images taken previously. So far, 90 percent of the data they've re-evaluated turned out not to be galaxy clusters, McDonald said in the statement. "But the fun thing is, the small number of things we are finding are sort of rule-breakers," he said.

The new report published the first results from the CHiPS survey, which has so far only confirmed the existence of one hidden galaxy cluster. Yet, scientists expect to find more in the future and to be able to use the clusters to learn more about the universe's expansion.

"Take for instance, the Titanic," McDonald said. "If you know where the two biggest pieces landed, you could map them backward to see where the ship hit the iceberg. In the same way, if you know where all the galaxy clusters are in the universe, which are the biggest pieces in the universe, and how big they are, and you have some information about what the universe looked like in the beginning, which we know from the Big Bang, then you could map out how the universe expanded."

Follow Kasandra Brabaw on Twitter @KassieBrabaw. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Kasandra Brabaw is a freelance science writer who covers space, health, and psychology. She's been writing for Space.com since 2014, covering NASA events, sci-fi entertainment, and space news. In addition to Space.com, Kasandra has written for Prevention, Women's Health, SELF, and other health publications. She has also worked with academics to edit books written for popular audiences.