Unstable Monster Galaxy Hosts Runaway Star Formation

Some 12.4 billion light-years from Earth, a monster galaxy can be seen forming stars 1,000 times faster than the Milky Way does. It's less of a mess than researchers expected — but its frenetic pace can't last.

Researchers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observatory in Chile have gotten the closest look ever at the galaxy, called COSMOS-AzTEC-1. So-called extreme starburst galaxies may be the predecessors of modern galaxies like the Milky Way, and so understanding them lends insight into how today's galaxies formed and evolved.

Researchers knew the galaxy was rich in star-forming gas when they first spotted it 10 years ago, but the details of the gassy giant revealed with ALMA weren't what they expected. [What Makes Starburst Galaxies Spawn at a Frenzied Pace? (Video)]

"A real surprise is that this galaxy seen almost 13 billion years ago has a massive, ordered gas disk that is in regular rotation instead of what we had expected, which would have been some kind of a disordered train wreck that most theoretical studies had predicted," Min Yun, an astronomer at University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and co-author on the new work, said in a statement.

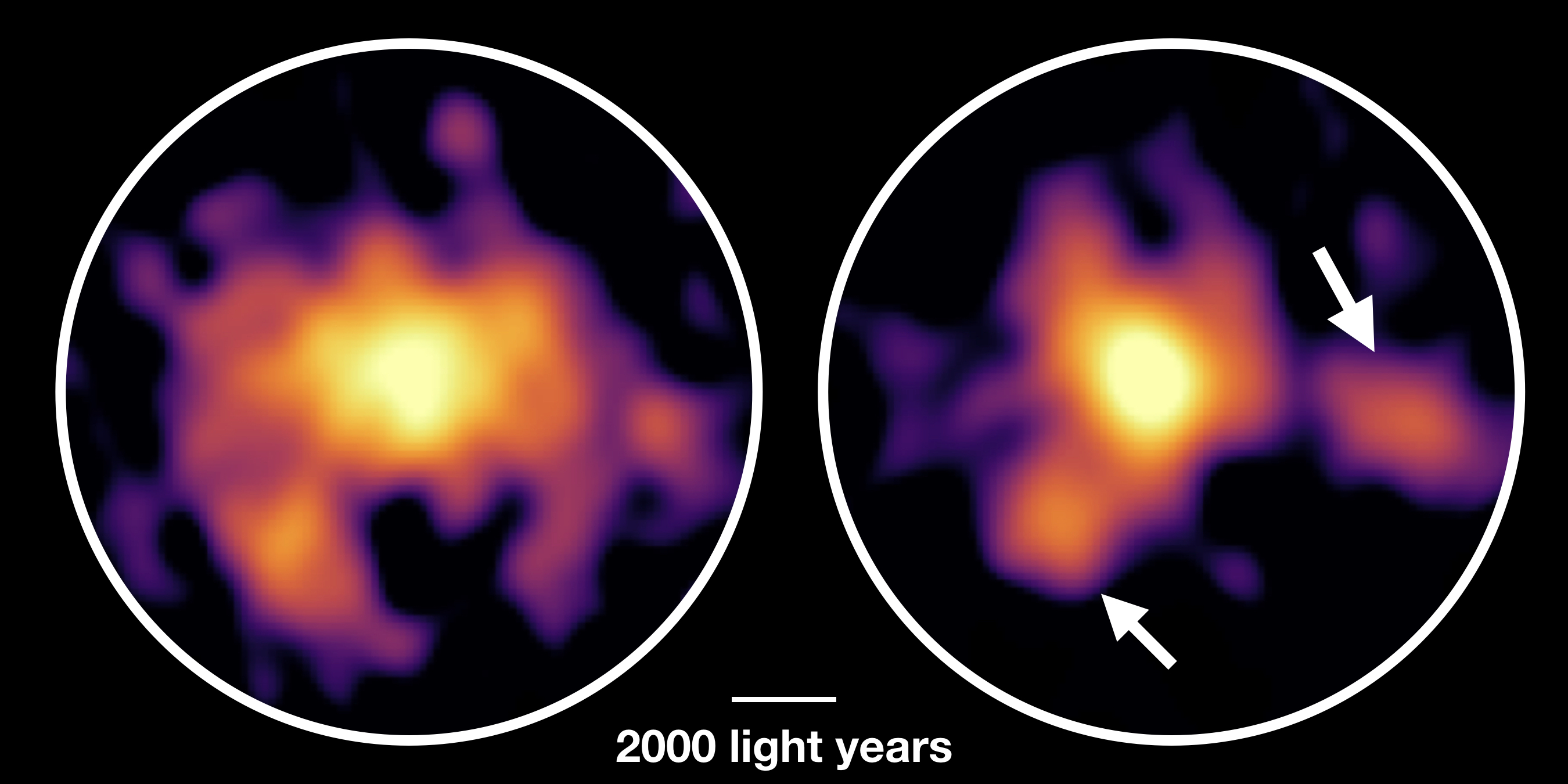

The ancient galaxy's structure held other surprises, as well. With ALMA, they saw that instead of just one dense cloud of material in the center, there were two extra blobs of star-generating gas.

"We found that there are two distinct large clouds several thousand light-years away from the center," Ken-ichi Tadaki, the study's lead author and a researcher at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Japan's National Astronomical Observatory, said in the statement. "In most distant starburst galaxies, stars are actively formed in the center. So it is surprising to find off-center clouds."

And its off-the-charts star formation comes from an inherent instability, the researchers said. In most galaxies, clouds of gas collapse and form stars, which eventually explode into supernovas, pushing gas outward again and slowing the pace of star birth. But in this galaxy, gravity is winning: More and more gas is collapsing into stars, without being pushed outward strongly enough to slow down.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers have been wondering for a long time how early galaxies could form stars so quickly, the researchers said.

"How these galaxies have been able to amass such a large quantity of gas in the first place and then essentially turn the entire gas reserve into stars in the blink of an eye, cosmologically speaking, was a completely unknown question about which we could only speculate," Yun said. "We have the first answers now."

If the early universe were populated with galaxies with structures like this one, they could have accumulated huge amounts of gas before suddenly blasting out stars in a runaway effect — although the researchers still don't know how the galaxy was able to build up gas in so stable a fashion before the reaction began.

And the ancient galaxy's life is likely fleeting: The researchers said it will be completely consumed in 100 million years, 10 times faster than other star-forming galaxies.

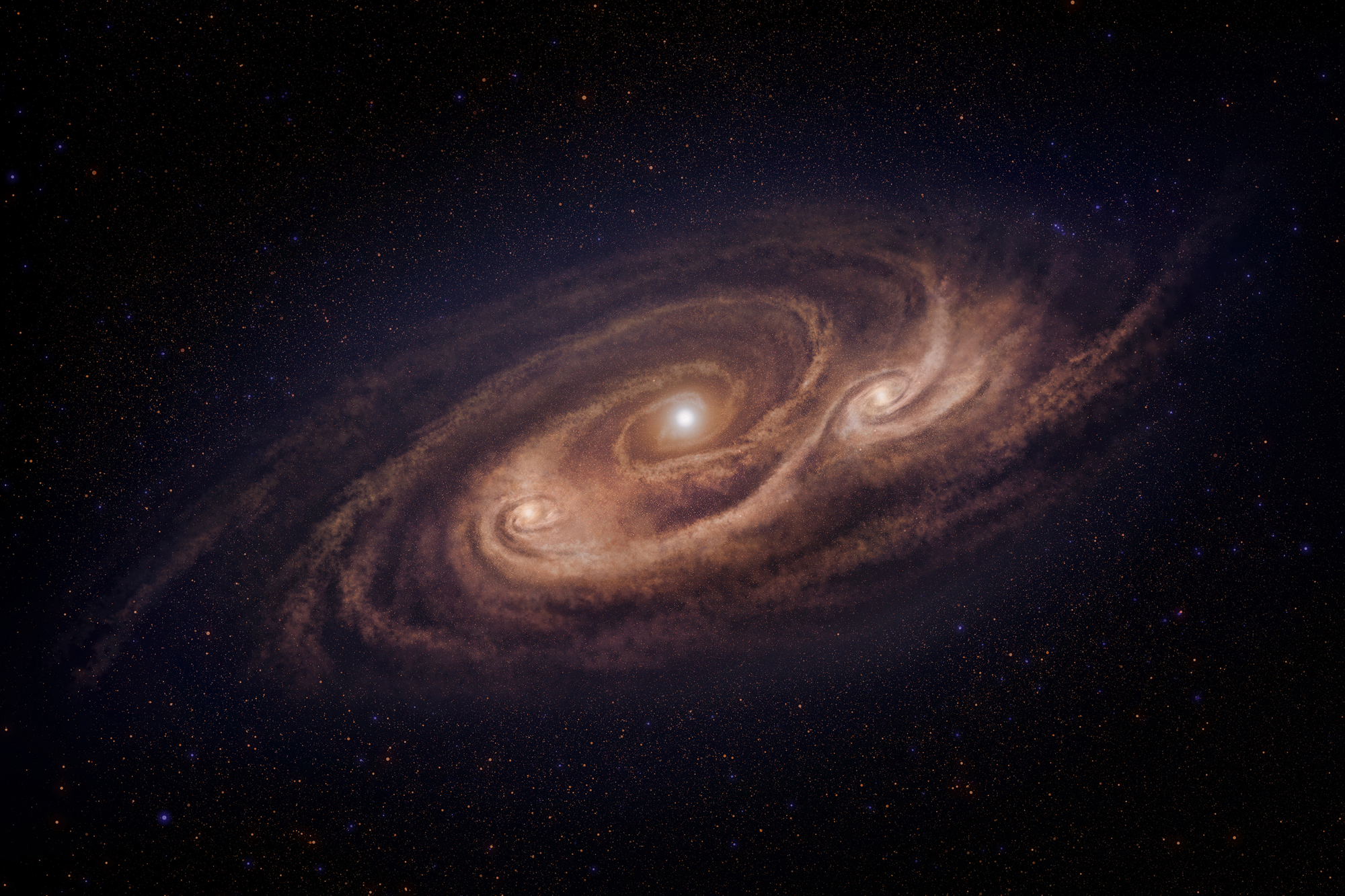

The researchers speculate that colliding galaxies could have merged to create the behemoth but would need more research — and to look at more ancient galaxies in this much detail — to evaluate how likely that origin is, and to learn more about our mammoth galactic predecessors.

The new work was detailed today (Aug. 29) in the journal Nature.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.