NASA Plans to Build a Moon-Orbiting Space Station: Here's What You Should Know

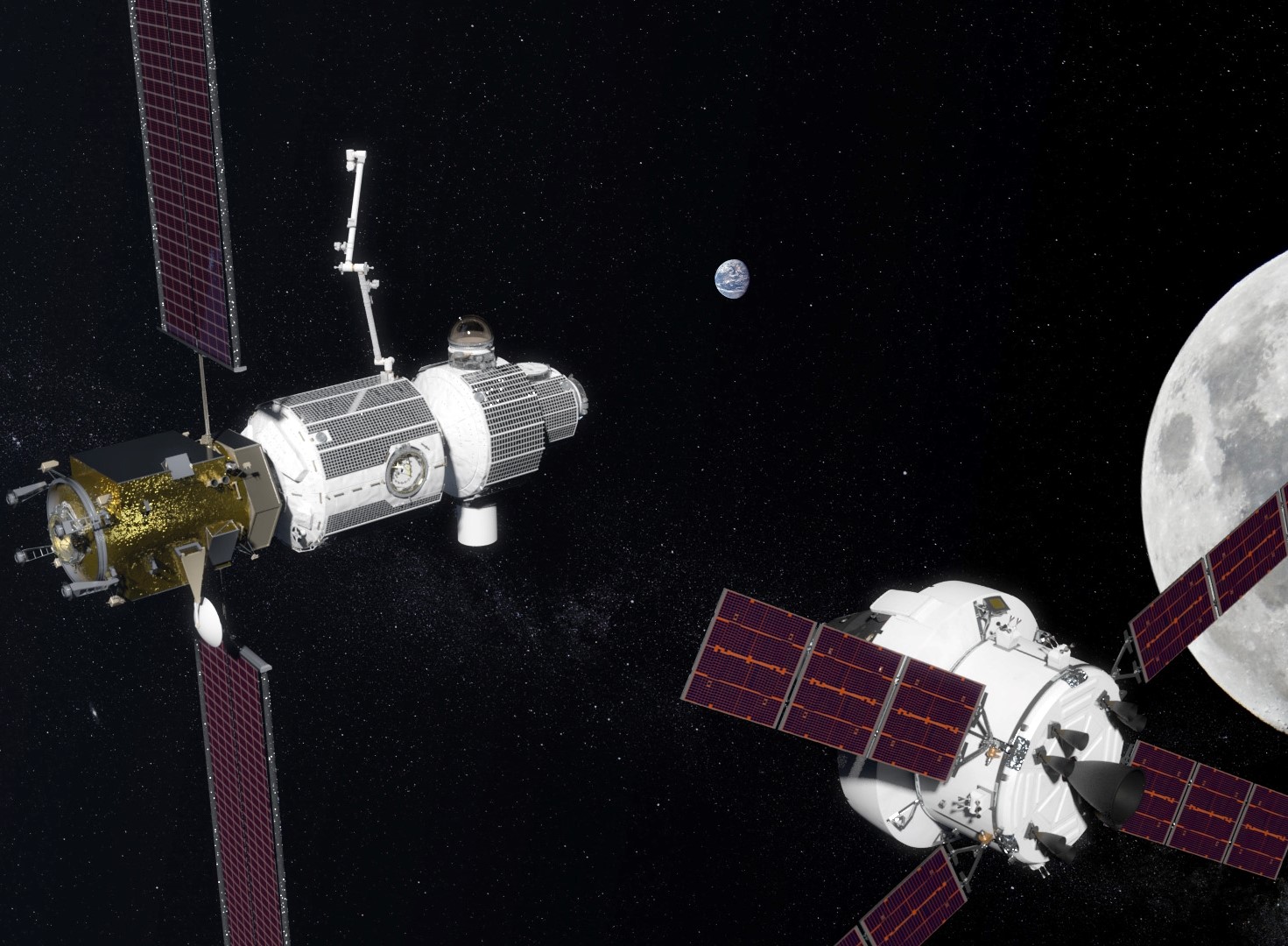

You've probably heard about the moon-orbiting space station that NASA plans to start building in the next half-decade.

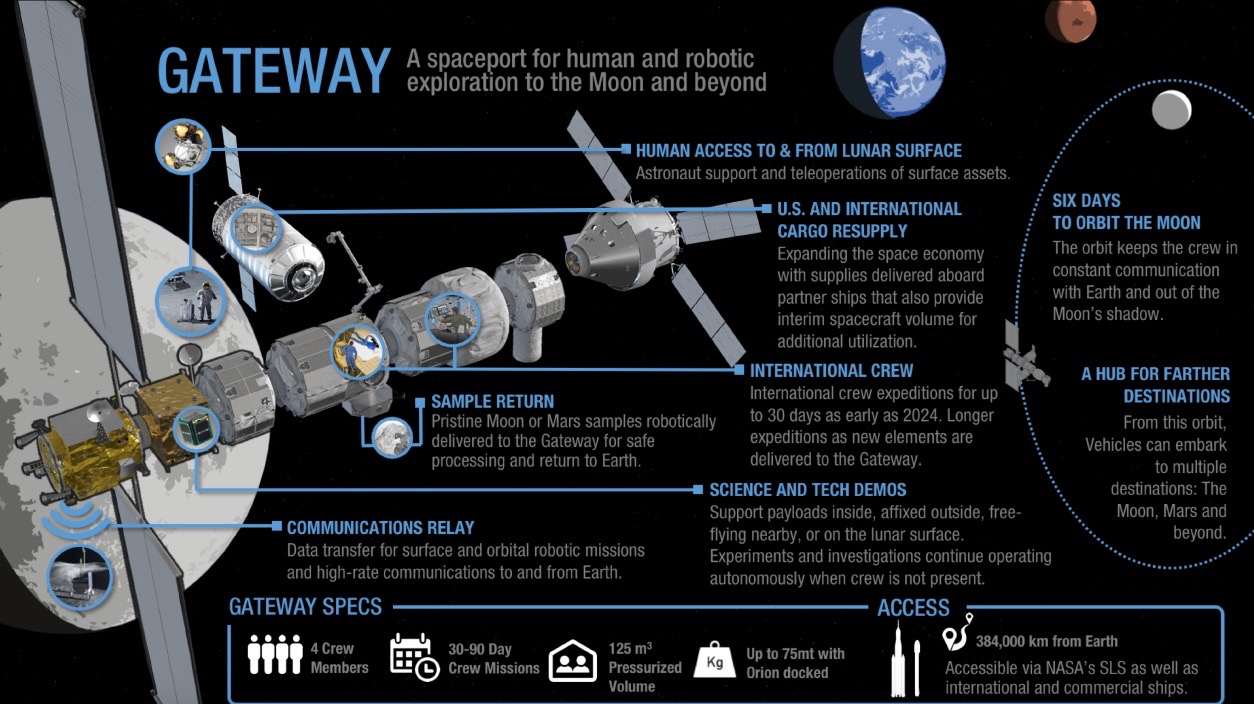

This outpost, known as the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, will help humanity extend its footprint out into deep space and also enable a variety of interesting scientific and commercial activities on and around the moon, NASA officials have said.

But maybe you're a little hazy on the details of the Gateway (a much nicer shorthand than the acronym LOP-G) — what it will look like, for example, or where exactly it will set up shop. If so, the following primer on the basics of this planned deep-space station should help. [21 Most Marvelous Moon Missions of All Time]

A small outpost

NASA plans to build and visit the Gateway using the agency's Space Launch System (SLS) megarocket and Orion deep-space capsule, both of which are still in development.

The first piece of the 55-ton (50 metric tons) outpost, its power and propulsion element (PPE), is currently scheduled to lift off in 2022. Other key components, such as a robotic arm, a crew habitat module and an airlock, will follow in relatively short order, if all goes according to plan. The Gateway could be ready to accommodate astronauts by the mid-2020s, NASA officials have said.

Those crewmembers won't have nearly as much room to roam as they do on the 440-ton (400 metric tons), Earth-orbiting International Space Station (ISS). As currently envisioned, the Gateway will feature a minimum of 1,942 cubic feet (55 cubic meters) of habitable volume, compared to the 13,696 cubic feet (388 cubic m) on the ISS.

The ISS typically houses six crewmembers at a time, who serve missions of five to six months apiece. And these missions overlap; rotating international crews have occupied the ISS continuously lsince November of 2000.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Gateway, however, will support a maximum of four crewmembers at a time, and they will be more or less isolated, living and working at the station for 30- to 90-day stints. Because getting NASA astronauts out to lunar orbit will require expensive (and, therefore, relatively infrequent) SLS-Orion launches, the Gateway will likely be uninhabited for most of the year — unless other users want to take advantage of the outpost, that is.

"It doesn't have to be U.S. crew. We're trying to use interoperability standards for both the docking, power, avionics, a lot of other systems," John Guidi, deputy director of the Advanced Exploration Systems division of NASA's Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, said in June during a presentation with the space agency's Future In-Space Operations (FISO) working group.

"The attempt there is to open up the ability for other nations, other companies, to dock," Guidi added. "They would have to bring their own resources. We won't have food, water, etc. available for everybody. We're just planning enough for our missions. But that is a capability we want to have in this Gateway."

There will be lots for Gateway dwellers to do. They could operate rovers on the lunar surface with virtually no commanding latency, for example, or take sorties down there themselves. And they'll doubtless conduct lots of scientific experiments aboard the outpost, just as ISS crewmembers do today. (Meanwhile, doctors and mission planners will be carefully monitoring how these astronauts cope mentally and physiologically with their deep-space environment.) [Moon Base Visions: How to Build a Lunar Colony (Photos)]

But the outpost will host and support research year-round, no matter how often astronauts visit, NASA officials have said. The agency envisions affixing a variety of scientific gear to both the interior and the exterior of the mini-station, and many of these devices will gather data autonomously.

A jumping-off point

The Gateway will, of course, be much more distant from Earth's surface than the ISS, which circles a mere 250 miles (400 kilometers) above our planet.

NASA plans to assemble the Gateway in a highly elliptical "near-rectilinear halo orbit," which will bring the outpost within 930 miles (1,500 km) of the lunar surface at closest approach and as far away as 43,500 miles (70,000 km). (Reminder, the moon lies about 238,900 miles, or 384,400 km, from Earth on average.)

This six-day orbit will keep the Gateway out of the moon's shadow at all times, permitting constant communication with Earth, NASA officials have said. And with this orbit, the outpost can serve as a jumping-off point, both for landers headed down to the lunar surface and for vehicles venturing out into deep space.

"We eventually want to go to Mars, and the systems that are going to take crew to Mars and back are going to be fairly large — very large," Guidi said.

As much as possible, NASA wants to avoid having to haul this heavy gear out of Earth's deep gravity well, to make Red Planet treks more efficient and cost-effective, Guidi added. And the Gateway should be able to help with that.

"So, we're thinking if we can use the SLS-Orion to take us to cislunar space, [in other words, to] go to the Gateway, we can move the Gateway a little bit in orbit — and the PPE is capable of doing that — dock to Mars-type transportation-habitation systems and send them off," Guidi said. Then, when those craft return, they can "again rely on SLS-Orion to make the link between the lunar environment and home," he said.

Step by step

The ball is already rolling on Gateway hardware design. For example, NASA expects to announce the prime contractor for the PPE in March of next year.

And five different companies — Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Bigelow Aerospace, Boeing and Sierra Nevada Corp. — are scheduled to deliver "ground prototypes" of their proposed habitat modules for testing sometime next year. (NASA is also negotiating with a sixth potential habitat-module contractor, NanoRacks, agency officials have said.)

If everything works out, NASA astronauts could set foot on the moon before the end of the 2020s, Guidi said. This goal is in keeping with President Donald Trump's Space Policy Directive 1, which instructs the agency to set up a long-term, sustainable outpost on the lunar surface.

That same directive also makes clear, however, that humanity's push out into the solar system should not end at the moon.

"Mars is still important. It's still the long-term goal," Guidi said. "But the near-term focus is more about our neighbor in cislunar space."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.