Take a Look Inside Lockheed Martin's Proposed Lunar 'Gateway' Habitat for Astronauts

NASA is taking a stepping-stone approach to the human journey to Mars.

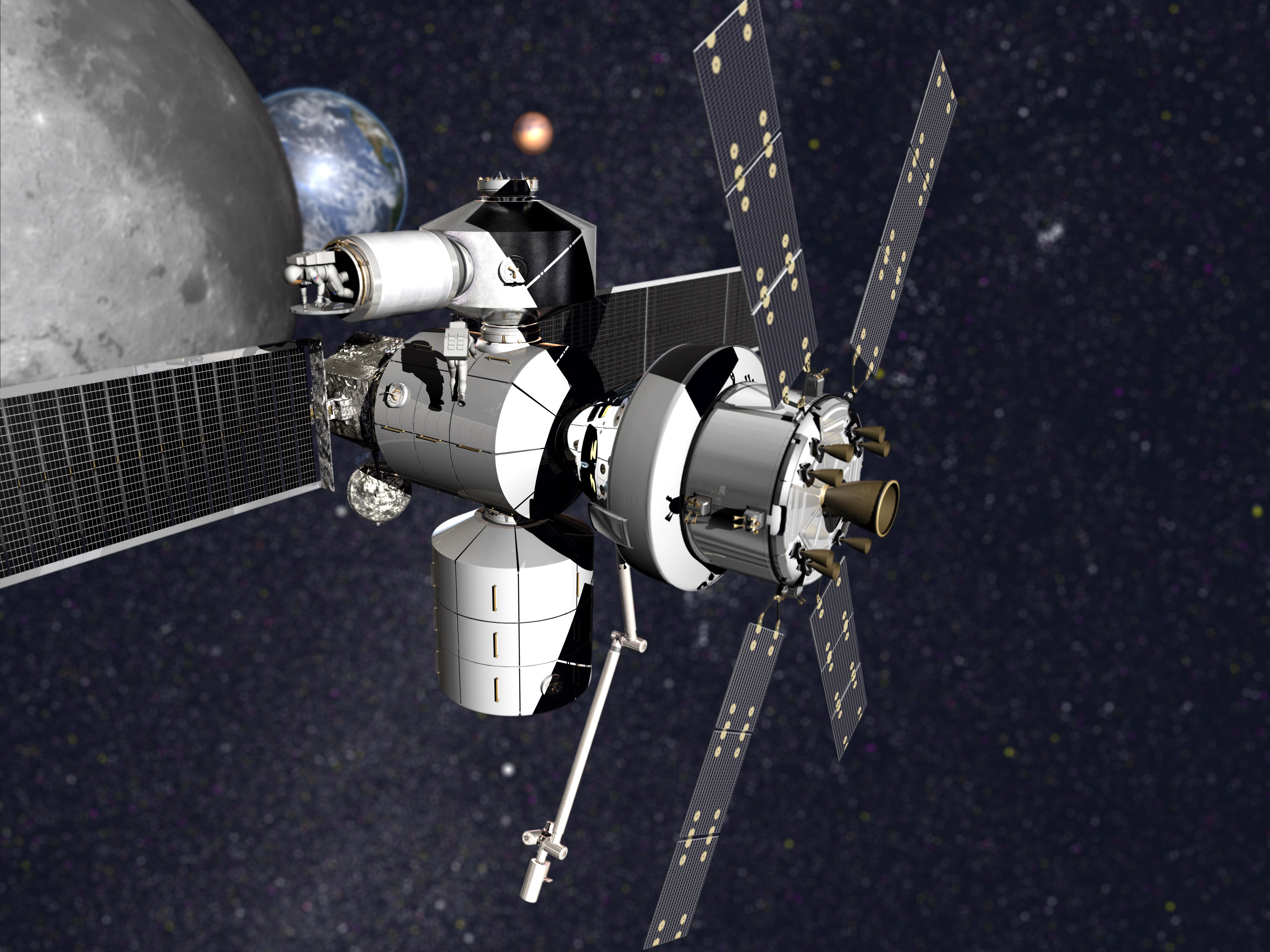

The agency plans to start building a moon-orbiting space station, called the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, in 2022. The Gateway will provide a place for humans to live for up to three months at a time, and it will continue to support scientific research even when nobody's on board.

The details of the Gateway are still being ironed out. Last year, NASA's Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships program (NextSTEP) awarded a total of $65 million to six different companies vying to provide the main habitat module for the outpost. If all goes according to plan, these companies will deliver full-size prototypes of their modules to the agency for testing by sometime next year. [21 Most Marvelous Moon Missions of All Time]

Lockheed Martin is one of those competitors.

According to Kat Coderre, Lockheed's NextSTEP habitat systems engineering lead, "The whole goal of Gateway … is to basically get humans a little deeper into space, so we'll have a place where we can learn to do both science and actually have human missions for long duration away from Earth, with the ultimate goal of getting us on a good Martian mission and having that first human mission to Mars."

The Lockheed Martin team is working on assembling a mock-up of the Gateway habitat module at a company facility near Denver, which Space.com got to tour this past summer. The mock-up allows engineers to try out new ideas before implementing them in the prototype currently being constructed at NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

"We are using an older piece of shuttle hardware, the [Donatello] MPLM — the Multi-Purpose Logistics Module — which was used to actually bring supplies to and from the space station," Coderre told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Donatello was one of three large modules built to transfer cargo from the payload bay of a space shuttle to the International Space Station. Donatello never made it into space; the MPLM was decommissioned and is now being used as test equipment for the Gateway habitat.

Using Donatello in this way allows the Lockheed team to perform extremely precise tests before handing the Gateway project off to NASA, Coderre said. NASA will then begin to include humans in the testing loop "to help burn down some early risk on design and to determine what key areas NASA really needs to focus on for crewed missions," she said.

Currently, the test article at KSC is set to be completed by January of 2019, Coderre said.

"It's going to happen real fast," she said.

In recent months, engineers have set the baseline for what every piece of equipment in Florida should look like, she added. The first test hardware is already set up, and the engineers are picking up speed. "We're going to be [moving] at a pretty rapid pace from now on," Coderre said.

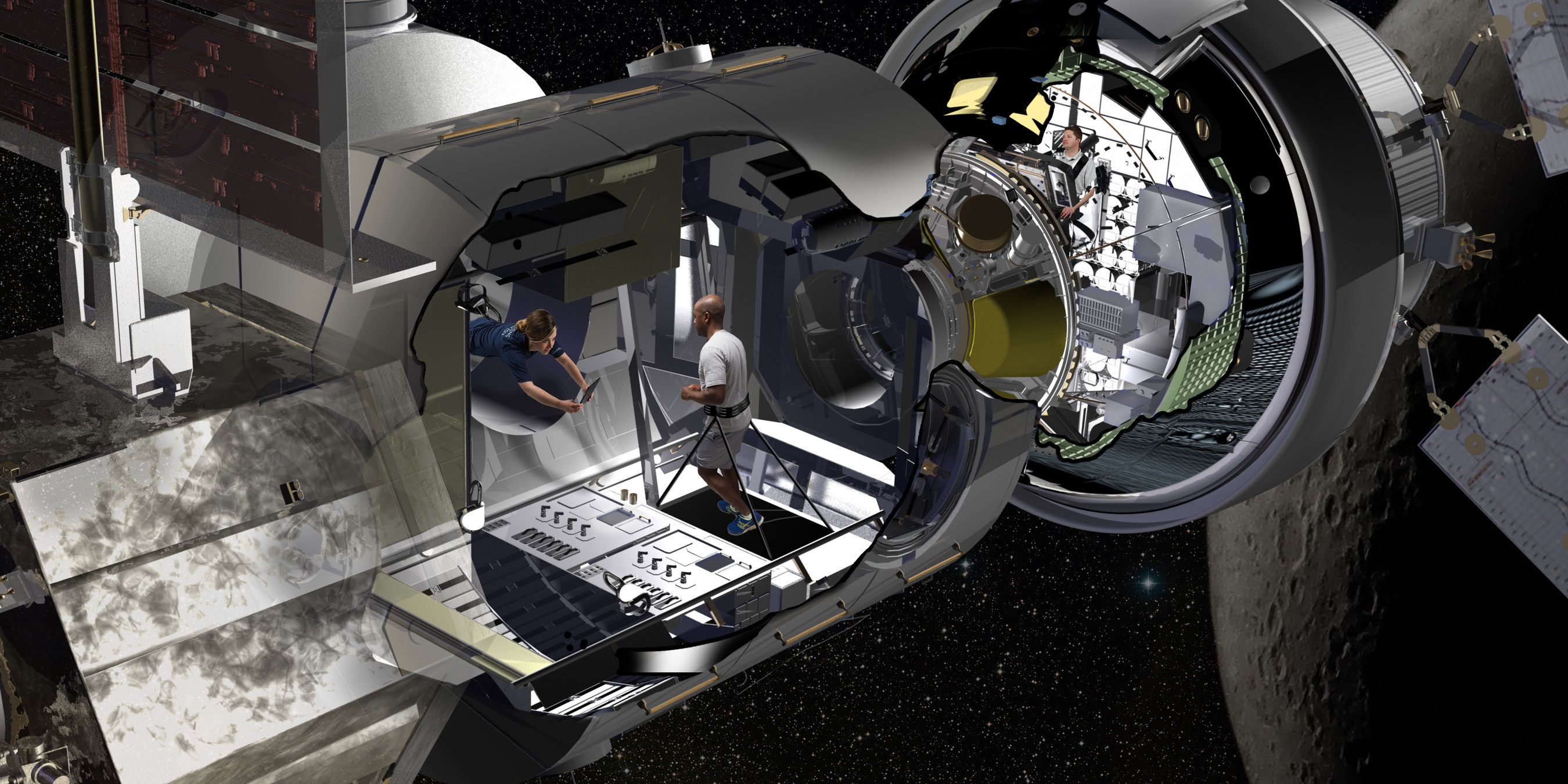

Tight living space

At about 15 feet wide and nearly 22 feet long (4.6 by 6.7 meters), the proposed Lockheed habitat is about as large as a bus or an RV. Once the Gateway is launched, astronauts would live in this confined space for as long as 90 days. The Denver mock-up, which emulated the decommissioned Donatello, was mostly empty space in June, but the final habitat 'will hold life-support systems, sleep stations, exercise machines, science lab space and robotic workstations.

According to Danielle Hauf, a Lockheed spokeswoman, the habitat's total pressurized volume is about 2,260 cubic feet (64 cubic meters). That compares to 691 cubic feet (20 cubic m) for the Orion capsule, the NASA spacecraft being built to carry humans into deep space. Orion will deliver crews to the Gateway habitat, where the vessel will remain docked.

Once the additional systems are installed, the habitable space will be much smaller, though Hauf said the final measurements will depend on how the spacecraft is configured — something the team is still working on. In any case, the final habitable volume will be a far cry from the 13,696 cubic feet (388 cubic m) of living space found aboard the International Space Station.

"We've always stated the need for at least two habitats," Coderre said. "Our architecture has been updated to show a second hab, and NASA's does now, too." She went on to say that to perform the right amount of science and test out new deep-space technology, it seemed clear that the habitat required "a little more space." [Cosmic Quiz: Do You Know the International Space Station?]

"And also for the crew's sanity," said Kerry Timmons, Lockheed's NextSTEP power, avionics and software lead.

One habitat would be for NASA's domestic logistics, while the other could be an international contribution, Coderre said. The habitat would also have ports that could work for visiting vehicles other than Orion, such as logistics, human vehicles, or robotic or human landers.

"It's really kind of a flexible platform where we can do a lot of different science, as well as different human exploration," Coderre said.

Chief among those is the Orion capsule, which Coderre called a "key element." Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor on the spacecraft, and both Coderre and Timmons came to the Gateway development team from the Orion team.

In addition to delivering astronauts to the habitat, Orion will also carry another important element: bathroom facilities. As it is envisioned now, the habitat plan does not call for a toilet. Instead, astronauts would return to Orion to answer nature's call.

The Gateway's Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) will form a bulkhead at the opposite end of Orion and will enable the outpost to be moved to various orbits around the moon, NASA officials have said.

The PPE, which is being developed separately from the habitat module, will host communications and command-and-control functions, and it will rely on solar electric propulsion (SEP) via a giant solar array. The PPE will be launched first via commercial rockets, then use SEP to move to its final orbit, while nNASA's in-development Space Launch System megarocket will carry the habitat and other elements into space.

"Each exploration mission will bring up a different element, integrate it into the Gateway, do the initial checkouts and then perform the rest of the science objectives for that mission," Coderre said.

Whichever habitat NASA ultimately selects will feature a hatch that allows astronauts to engage in extravehicular activities (EVAs) outside of the module. Astronauts might take EVAs to perform maintenance or science experiments. These excursions could also help test out new spacesuit technology, Coderre said

"The idea is that we want the capability to test out advanced spacesuit technology for spacewalks," Coderre said. "We know that could be an integral part of any further deep-space mission." [Evolution of the Spacesuit in Pictures (Space Tech Gallery)]

A cargo pod opposite the EVA hatch would allow for completing various logistic tasks, including resupplying the station and taking out the trash. "You can't just open the window and throw the trash out," Coderre said with a laugh. She added that figuring out how to store and dispose of trash and consumables is one of the biggest concerns, particularly because of bacterial growth and odors.

The mock-up in Colorado is a lower-fidelity version of the product. A more detailed prototype, using the Donatello MPLM, was unveiled in Florida in August 2018.

Part-time crew

Despite thorough planning for how to handle astronauts on board, NASA's Gateway habitat will most likely be crewed for just a few months out of the year, NASA officials have said. The rest of the time, it will be empty. But that doesn't mean nothing will be happening aboard the station.

"We're looking at other different operation concepts where we can do other uncrewed activities, different science and other experiments that can actually be done without humans there," Coderre said.

These options include remote telerobotics that can be directed from the ground. Another possibility is the addition of a robot, which could move across the module on a rail. When Space.com visited in June, a robotic arm was set up to pick pretend strawberries and pick up objects on a tray via a remote console through the use of virtual reality.

Virtual and augmented reality have played a strong role in the development of Lockheed's habitat. By overlaying the real hardware with simulations, engineers were able to visualize the capsule more easily, allowing them to save time and catch potential problems early.

"We're looking at those concepts where we can do different virtual and/or distinct activities while there is no crew," Coderre said.

Lockheed is also building a "Deep Space Avionics Integration Laboratory" in Houston to demonstrate command and control between Orion and the Gateway. The lab will help reduce the risk associated with critical data communications between the Gateway's elements and will provide an environment in which astronauts can train for various mission scenarios, company representatives said.

Lockheed is competing with Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp., Northrop Grumman, NanoRacks and Bigelow Aerospace to develop a Gateway habitat. NASA will review the plans and award a contract sometime next year. That agency aims to launch the PPE in 2022 and have the Gateway ready for astronauts by the mid-2020s.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd