How Space Exploration Can Teach Us to Preserve All Life on Earth

Two conservation scientists have published an editorial in the prestigious scientific journal Nature today (Sept. 13) calling for more space on Earth to be set aside for wildlife. But what does that mean for space exploration, and what does our history in space teach us about the wisdom of such an effort?

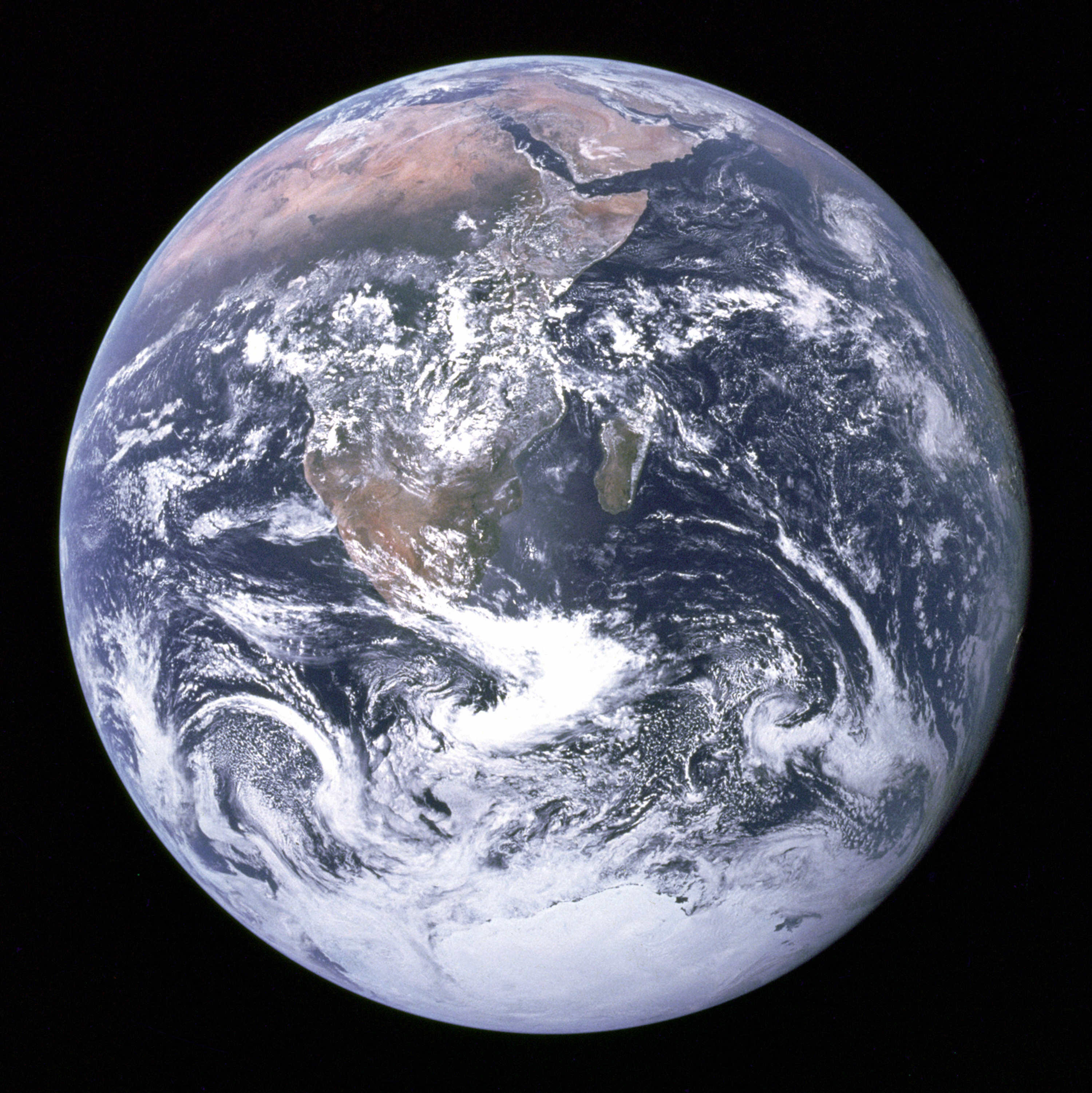

Space exploration and the environmental movement have long been intertwined, with the latter galvanized by space-based imagery like the Apollo 17 crew's Blue Marble photo of the full Earth disk and the Voyager mission's Pale Blue Dot image of Earth taken across 4 billion miles (6 billion kilometers) of our solar system.

Before space exploration began, "there was no perception of Earth as a single entity and certainly no context for it in space," Lisa Ruth Rand, a historian of science, technology and the environment who is currently the American Historical Association and NASA fellow in space history, told Space.com. [Wild! Scientists Are Watching Baby Turtles from Space]

"That was revolutionary at the time," she said of the sentiments inspired by the Blue Marble image. "Not only are we alone in space in this hostile, barren void, but also we are all in it together," she said.

Now, the view of Earth from orbit has become commonplace, but space is still changing the way we think about Earth. Over the past two decades, as exoplanet studies have blossomed, the connection has taken on a new spin as we identify more and more worlds around other stars — but still find ourselves liking Earth best. That's true closer to home as well, where even as we continue to learn about the worlds around us, we fail to find life, much less vibrant, complex ecosystems.

"This is a wonderland," John Rummel, a senior scientist at the SETI Institute and a former planetary protection officer at NASA, told Space.com of Earth. "We have been ignorant about the things that we have been doing to the Earth's biosphere and it is much more complex and amazingly interdependent than anything we're likely to see in this solar system."

Can we build a biosphere?

The new editorial calls for meeting the goals that governments around the world have already agreed upon at a 2010 conference, of protecting at least 17 percent of land and 10 percent of ocean areas by 2020 — goals that humans currently fall far short on, at just 14.7 and 3.6 percent, respectively.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But those targets may not be what we need to keep Earth's ecosystems functioning, some planetary scientists fear. "Now we are talking about a bioengineered world, we are not talking about a planet anymore; we are talking about a national park on a planetary level and it's not a biosphere anymore," Nathalie Cabrol, an astrobiologist at the SETI Institute, told Space.com. "We are going to create an artificial bubble when what we had was a beautifully working natural system."

Cordoning off land and seas to manage all the creatures around us isn't so different from building the type of artificial biospheres would-be explorers have dreamed up for other planets and moons. The similarity could mean that space endeavors offer lessons for managing life here on Earth — but those lessons may not be as encouraging as we might wish.

"I think in understanding how to build an artificial biosphere and make it work we will provide more information about how to keep this one going," Rummel said. That said, there won't be an easy solution. "Even at best, any biosphere that we could construct for centuries to come is going to be a mere shadow of what we have every day on the Earth," he said. [NASA's Best Earth-from-Space Photos by Astronauts (Gallery)]

And even without ever having laid a brick or planted a seed on another world, humans have dipped their toes in the world of biosphere construction. Perhaps the most enthusiastic experiment came in 1991, when a crew of eight stepped foot inside a facility dubbed Biosphere 2 (Biosphere 1 being Earth, of course) in the middle of the Arizona desert.

The two-year experiment was meant to be a self-sustaining miniature replica of Earth with 3,800 species, but while all eight crewmembers survived, it was a troubled experience. One crewmember briefly left the biosphere for emergency medical care. Sweet potatoes thrived so much better than most crops in the high carbon levels that crewmembers' skin picked up a faint orange sheen from eating so many of them. A whopping 40 percent of the species humans had carried with them went extinct.

"It didn't turn out well for a majority of the species — including the humans — that were living there," Rand said. "Ultimately, there's a lot of challenges to creating life in microcosm elsewhere, even here."

She used the term "hellish" to describe a video of life in the facility, which was overrun by invasive ants and cockroaches and bereft of species crewmembers had wanted to retain. One of the first to go was the honeybees, which unbeknown to the humans who built the biosphere, couldn't see in most of the facility. They were found dead, clustered near an emergency exit, the only place where the biosphere's glass let in the ultraviolet light bees use to navigate, Rand said.

"Even this seemingly very controlled experiment still had problems with biodiversity," Rand said. That's a powerful lesson the history of this sort of endeavor can offer about the limitations of our power to build ecosystems ourselves. "If we can take advantage of what's already here and work with nature instead of trying to recreate it somewhere else, we have a much greater chance of success," she said.

We can't run away from our problems

While space offers a new perspective on Earth and its problems, space scientists cautioned against the common viewpoint that other planets can offer refuge if Earth becomes untenable for human existence.

That's the wrong approach, according to some. "We are not going to fix any of the problems that we have on Earth by going to Mars," Cabrol said. "If we are not capable of understanding our problems here on Earth," she said, "we are just going to transfer this mentality onto another planet." (Rand added that such projects would almost certainly perpetuate the same power relationships and inequities that have shaped terrestrial societies for millennia.) [The BFR: SpaceX's Mars-Colonization Architecture in Images]

And fleeing is particularly risky given how grim life on another planet is likely to be for the foreseeable future. "Maybe what Mars is going to give us is a consciousness of how beautiful, precious, fragile Earth is." Cabrol said. "We should not use planetary exploration as an escape."

That isn't to say there's nothing space can offer us when it comes to solving our problems, Cabrol said. She said that one of the gifts of planetary exploration is that it puts new challenges in our path and forces us to solve them promptly, creatively and often remotely. That's the sort of skill with obvious implications for life on a fast-changing Earth.

And if we continue to lose biodiversity here on Earth, space exploration may slip out of reach, Rummel said, as species losses ripple through food webs and cause accelerating change. "The very basis of the economies and support systems on the Earth that allow us to envision going elsewhere with both robots and people, those are the things that are in jeopardy." He points to the host of ecosystem services we rely on without blinking an eye, from insects that pollinate crops to plants that filter air and soil that retains stormwater.

The same is true of climate change, which is raising temperatures and strengthening storms around the world. NASA satellites have spent the week monitoring Hurricane Florence and a host of other tropical storms that will leave death and destruction in their wakes — and one of which has also delayed a cargo launch to the International Space Station. Last year's hurricanes Irma and Harvey damaged Kennedy Space Center and shuttered Johnson Space Center.

But biodiversity loss and climate change are both massive, incremental, depressing problems — precisely the sort of challenge humans hate to tackle. "Innovation is sexy and fixing things that already exist that can be repaired is not," Rand said. "It's much more fun and glitzy to imagine trying to build something new in a new place."

But here, the history of space exploration may be able to offer a more productive mindset, despite the temptation of looking to the next horizon and the next mission. NASA has a long track record of extending missions and reprogramming damaged telescopes or robots already at work. Perhaps those examples, coupled with the nitty-gritty data and big-picture views that the agency offers of our home planet, can teach us to embrace a culture of conservation.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.