Watch a Satellite Net a Cubesat in Awesome Space Junk Cleanup Test

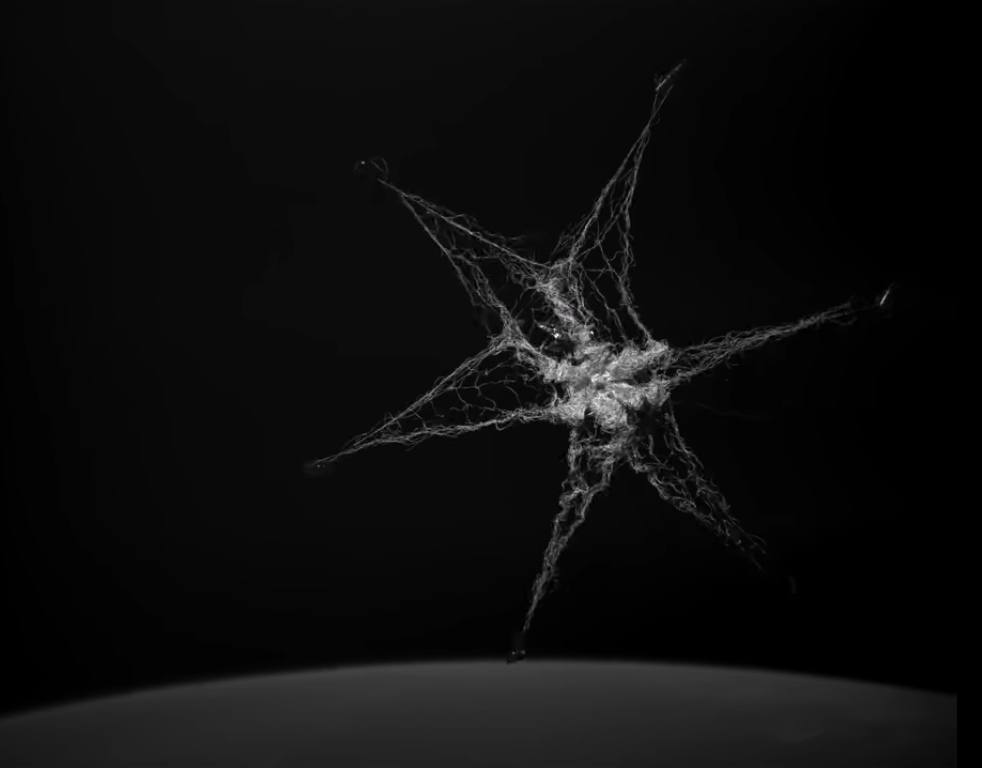

The video is stunning: A satellite in orbit fires a net to snare a nearby target in the pioneering demonstration of space-junk-cleanup technology.

The space net demonstration, which occurred Sunday (Sept. 16), is part of the European RemoveDebris mission, designed to test active debris-removal techniques in space for the first time. The target wasn't an actual piece of space junk but a small cubesat measuring (10 x10 x 20 centimeters, or 4 x 4 x 8 inches) that was released by the main RemoveDebris spacecraft shortly before the capture experiment.

"It went very well," said RemoveDebris mission principal investigator Guglielmo Aglietti, director of the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom. "The net deployed nicely, and so did the structure attached to the cubesat. We are now downloading the data, which will take a few weeks, since we only can do that when we have contact with the satellite. But so far, everything looks great." [7 Ways to Clean Up Space Junk]

RemoveDebris is a refrigerator-size spacecraft built by satellite manufacturer Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL), which is part of the RemoveDebris consortium together with the University of Surrey, the aerospace company Airbus and other European companies. It's designed to test space-junk-cleanup methods in orbit. In addition to the debris-catching net, the satellite is equipped with a small harpoon, a visual-tracking system and a drag sail.

Novel space-junk-cleanup tech

The net demonstration is the first test so far for RemoveDebris, and it began when the satellite released its cubesat target on Sunday.

Once the cubesat drifted about 19 feet (6 meters) from the chaser RemoveDebris craft, the satellite deployed a 3-foot-wide (1 m) inflatable structure that increased the object's size to match that of a real target. Then, the chaser satellite ejected the net using a spring-loaded mechanism. The entire sequence was preprogrammed and took about 2 to 3 minutes to complete, Aglietti said.

He told Space.com that the RemoveDebris team couldn't use an actual piece of space junk, because international laws consider even defunct satellites to be property of the entity that launched them. Thus, it would be illegal to catch other people's space debris, he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ingo Retat, who led the team at European space manufacturer Airbus, which designed the net, said it took six years of testing in parabolic flights, special drop towers and vacuum chambers for the engineers to gain enough confidence to send the technology to space.

"Our small team of engineers and technicians have done an amazing job moving us one step closer to clearing up low Earth orbit," Retat said in a statement.

Interest in active space-debris-removal technology has increased in recent years as the number of spacecraft and satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) has risen. Too much debris from defunct satellites or rockets could threaten newer satellites in orbit, because a hit from even a tiny piece of junk could destroy a satellite, experts have said.

Satomi Kawamoto, of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), said in a conference last year that more than 100 objects need to be removed from LEO at the rate of five per year to prevent the so-called Kessler syndrome — an unstoppable cascade of collisions predicted in the 1970s by NASA scientist Donald Kessler. This collision cascade would generate a massive amount of fragments and make operating in the space around Earth unsafe.

A space-debris net

The net consists of ultra-lightweight polyethylene Dyneema, which is commonly used to make mountaineering ropes. Six weights attached to the net ensured that it would spread to its full size of 5 m (16 feet) across, said Retat.

"The weights are actually small motors that are used to close the net around the debris," Retat said. "They run on a timer that begins counting down once the net has been deployed, and [they] automatically tighten up to trap the object."

In an operational setup, the net would be connected to the chaser spacecraft with a tether. After the capture, the chaser spacecraft would fire its engines and drag the space junk into Earth's atmosphere, where the object would burn.

For this first-time attempt, the engineers left the tether out, as it could cause some unexpected complications, Aglietti said. For example, the satellite could rebound and hit the main RemoveDebris spacecraft, which still has three more experiments to run.

Aglietti said the cubesat wrapped in the net will fall out of orbit naturally over time. It should remain in orbit no more than a year.

More tests to come

RemoveDebris was delivered to the International Space Station in April and deployed by astronauts in June.

The 5.2-million-euro ($18.7 million) mission, funded by the European Union, will next validate a vision-based navigation system designed to track and analyze pieces of space debris. In early 2019, RemoveDebris will test another Airbus-led active-removal technology: a pen-size harpoon that will be fired into a fixed plate attached to a boom that will extend from the main spacecraft.

The campaign will conclude in March 2019, when RemoveDebris will deploy a large sail designed to increase the craft's atmospheric drag and speed up its re-entry. Ultimately, the spacecraft will burn up as it re-enters the atmosphere.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.