Dust Storms Rage on Saturn Moon Titan, Just Like on Mars and Earth

Images from the 1930s captured the immensity of the American Dust Bowl, and modern snapshots reveal massive "haboob" dust storms intensely rolling over the Sahara Desert. Now, astronomers have taken pictures of something stunningly similar on an altogether alien location: They observed dust storms on Saturn's moon Titan.

The discovery of dust storms blowing across Titan's equatorial region makes the moon the third body in the solar system, after Earth and Mars, known to have the tempests.

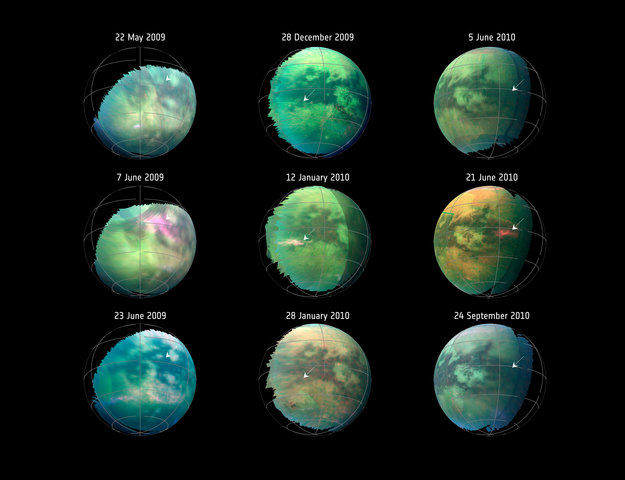

Data from the Cassini mission helped researchers discover Titan's dust storms, according to NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Cassini's mission to Saturn and the planet's many moons lasted from 2004 until 2017, when the probe plunged into the ringed planet's clouds to disintegrate. The death dive helped avoid contaminating the Saturn system with Earth microbes. [Amazing Pictures of Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

"Titan is a very active moon," said Sebastien Rodriguez in a statement from NASA and ESA. Rodriguez is an astronomer at the University Paris Diderot in France and the lead author of the paper, published Monday (Sept. 24), detailing the team's findings.

"We already know... about its geology and exotic hydrocarbon cycle," he said. "Now, we can add another analogy with Earth and Mars: the active dust cycle."

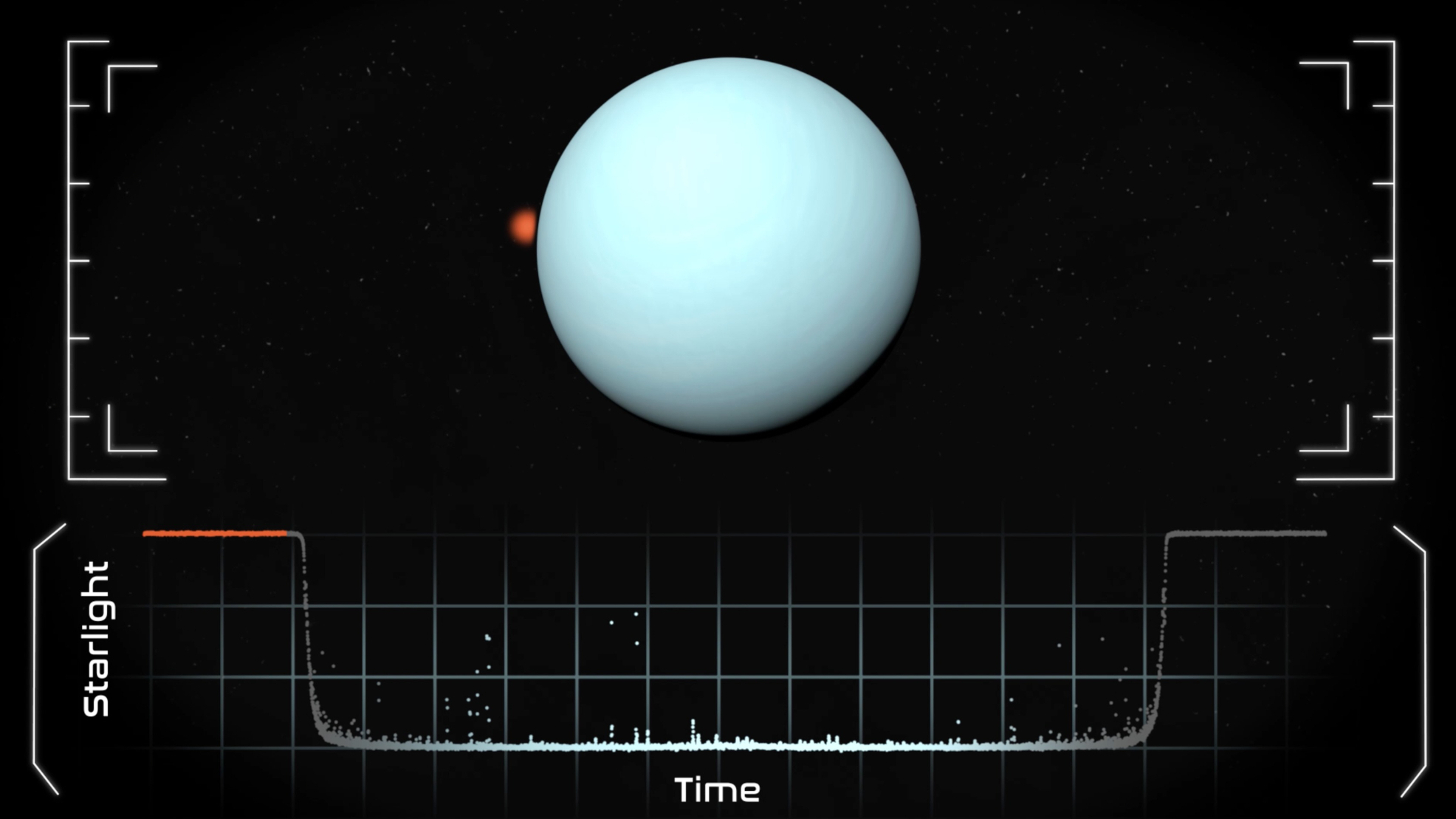

Just like the Atlantic Ocean produces the wet hurricane season now occurring on Earth, the methane and ethane on Titan form powerful storms near its equator as the sun causes those hydrocarbon molecules to evaporate. This unique methane cycle was first detected by Rodriguez's team, when they spotted three odd, equatorial brightenings in some of Cassini's infrared images.

Initially, the team thought the bright spots in Cassini's 2009 and 2010 images of Titan's northern equinox were just these methane clouds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

According to the space agency's statement, the researchers ran models that indicated that these features were related to Titan's atmosphere but located close to the surface. The team ruled out terrain as a cause, because land formations would have had a different chemical signature and would obviously remain visible for much longer than spots did. The bright spots "were only visible for 11 hours to five weeks," ESA officials said.

Because the features were close to the surface and located over the dune fields around Titan's equator, the team deduced that the bright spots were clouds of dust moving across the distant deserts.

The study detailing the findings was published on Monday (Sept. 24) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.