Super-Fast Stars in the Milky Way May Be Visitors from Beyond

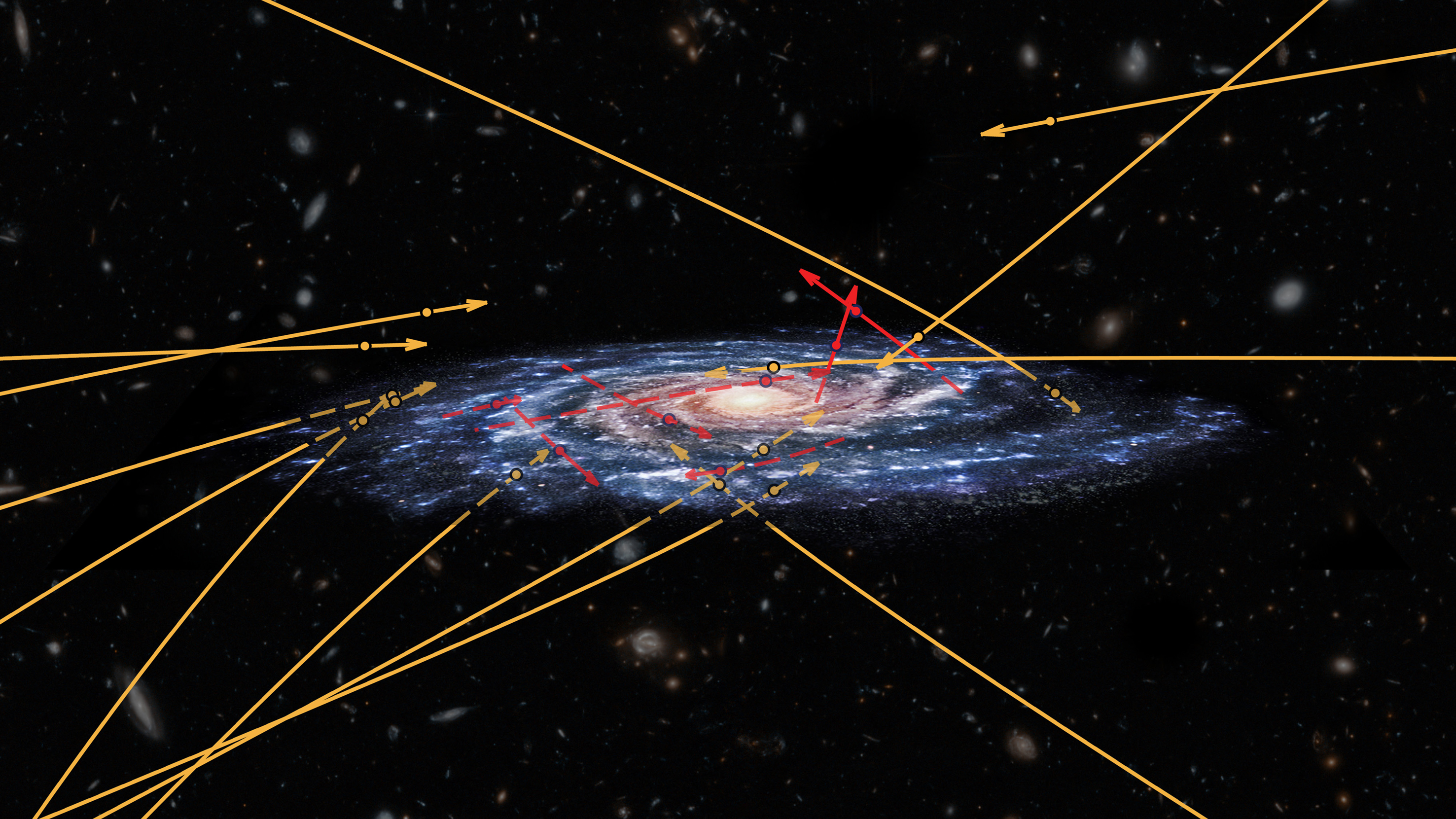

The cosmic "merry-go-round" that is our rotating Milky Way galaxy may not be the reason stars are whizzing by and seemingly flying off at high speeds.

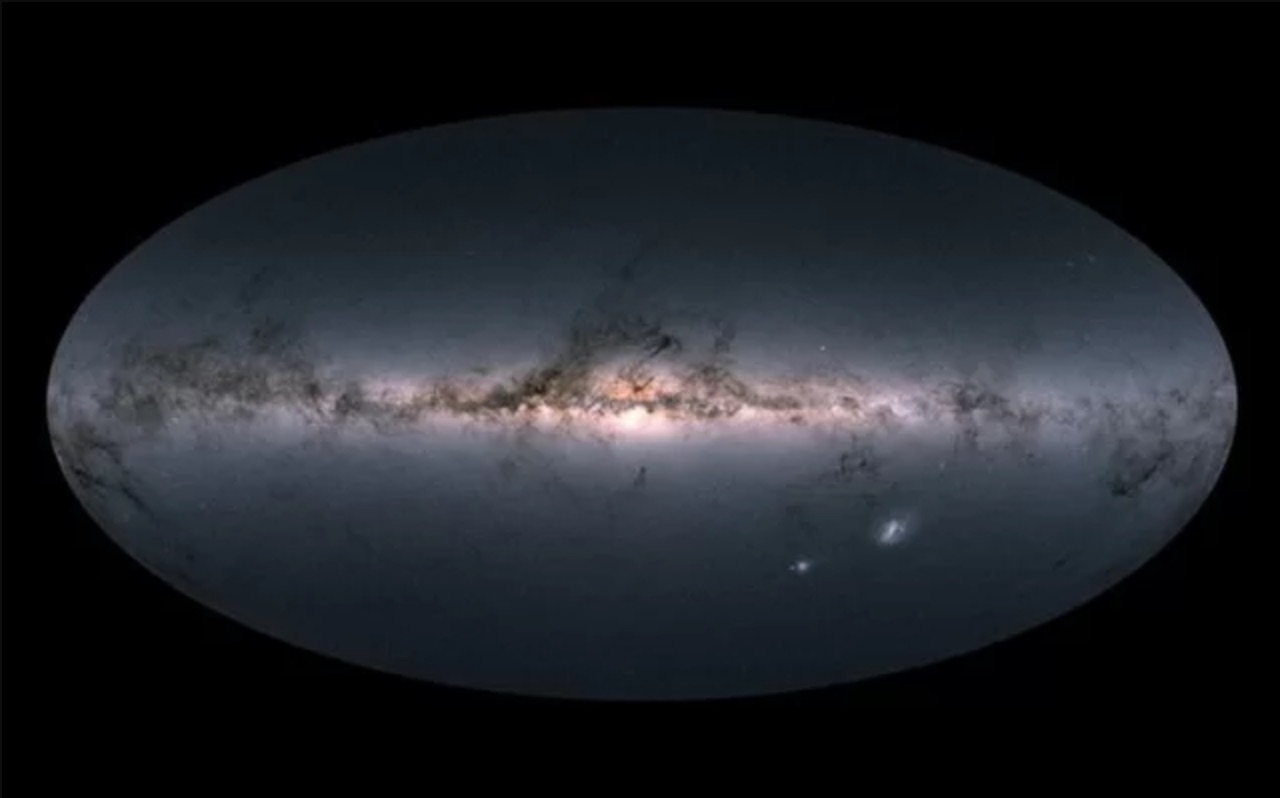

A team of astronomers noticed something interesting when they were sifting through the recently published second data release from the Gaia mission. The European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Gaia spacecraft in 2013, and the new data release includes observations made between July 25, 2014, and May 23, 2016, according to ESA.

The data offers the positions of nearly 1.7 billion stars, and their motions can tell astronomers a lot about what our galaxy used to be like. Stars travel at different speeds and the very fastest are called hypervelocity stars. Using a level of precision that sometimes "equates to Earthbound observers being able to spot a Euro coin lying on the surface of the moon," ESA officials said in a statement describing the mission, Gaia is able to gather observations about these hypervelocity stars.

Researchers thought the black hole at the center of the Milky Way was responsible for flinging out these stars. They thought the stars originated from the center of the galaxy, and that this black-hole interaction caused their high-speed journeys toward an exit of the Milky Way.

"Of the seven million Gaia stars with full 3D velocity measurements, we found twenty that could be traveling fast enough to eventually escape from the Milky Way," said Elena Maria Rossi, one of the authors of the new study, which was detailed in a recent statement by the Royal Astronomical Society in the U.K.

Or, they could be "intergalactic interlopers."

"Rather than flying away from the Galactic centre, most of the high-velocity stars we spotted seem to be racing towards it," co-author Tommaso Marchetti said in the statement. "These could be stars from another galaxy, zooming right through the Milky Way."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Stars can be accelerated to high velocities when they interact with a supermassive black hole," Rossi added. "So the presence of these stars might be a sign of such black holes in nearby galaxies. But the stars may also have once been part of a binary system, flung towards the Milky Way when their companion star exploded as a supernova."

Rossi said studying these hypervelocity stars will answer questions about how nearby galaxies behave.

To find out where they come from — some potential origins include the Large Magellanic Cloud or the Milky Way's halo — new data will be needed. Royal Astronomical Society officials said at least two more Gaia data releases are scheduled in the 2020s.

The study detailing these findings was published Sept. 20 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.