Hunting for Mini-Moons: Exomoons Could Have Satellites of Their Own

Moons could possess moons of their own, researchers say.

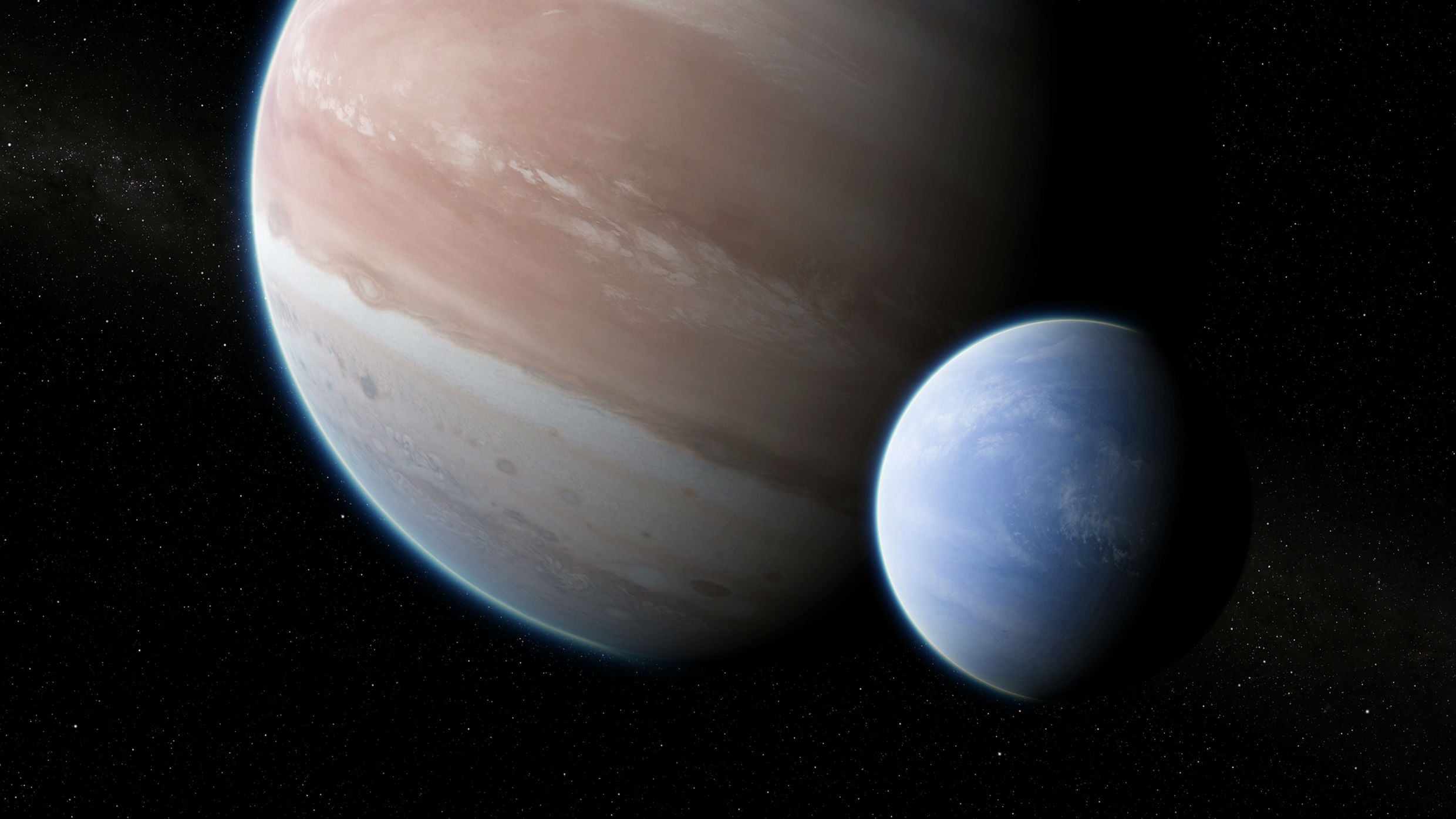

A newfound candidate to be a giant alien moon, Kepler-1625b-i, may even possess one or more submoons that once had surfaces habitable by life as we know it, a new study finds. That moon is located nearly 8,000 light-years from Earth.

Over the past two decades or so, astronomers have confirmed the existence of nearly 3,800 exoplanets, or planets around other stars. This month, scientists said they had discovered what may be the first known moon of an exoplanet. The moon, Kepler-1625b-i, may be about the mass of Neptune, far larger than any moon in our own solar system. (Neptune is about 17 times Earth's mass.) [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

The planet-size nature of Kepler-1625b-i raises the question of whether moons could have their own moons. And in another pair of recent studies, researchers said that "submoons" or "moon-moons" might indeed be possible.

One research group analyzed the orbits of hypothetical submoons about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter. Whether a submoon's orbit remains stable depends on the body's complex interactions with the planet and moon it calls home; the gravitational pulls of the planet and moon can result in tidal forces that could send a submoon flying into space or crashing into the planet or moon.

The scientists found that the submoons they modeled could survive only in wide orbits around large moons at least 600 miles (1,000 km) wide. In other words, if Kepler-1625b-i exists, it could host a submoon. However, it will likely be a long time before scientists will have the technology to detect submoons, study co-author Sean Raymond, an astrophysicist at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Space.com.

The researchers determined that submoons are unlikely to last around moons that are small or too close to their host planet, which is the case for most of our solar system's moons. However, the scientists' work suggests that a handful of known moons in Earth's solar system are capable of hosting long-lived submoons: Saturn's Titan and Iapetus, Jupiter's Callisto, and Earth's own moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I didn't expect that," Raymond said. "Incidentally, some researchers have proposed that Iapetus did indeed have a submoon that is responsible for its equatorial ridge but that [it] was lost." Raymond and study lead author Juna Kollmeier at the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington at Pasadena, California, detailed their findings online Oct. 8 in a study that they plan to submit to the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Raymond added that "it's hard to imagine a planet hosting subsubmoons — moons of submoons — because everything gets closer and closer together and tides are even stronger. That means that only teeny, tiny subsubmoons could exist."

Intriguingly, Kepler-1625b-i's host star is similar in mass to the sun, and the moon's host planet orbits this star at about the same distance as Earth does the sun. This suggests that the exoplanet and exomoon may have, at some point, been within their star's habitable zone, the area around the star warm enough for standing bodies of liquid water to survive without getting evaporated or frozen away. There is life virtually wherever there is water on Earth, so the hunt for alien life often focuses on habitable zones.

Both Kepler-1625b-i and its companion planet are gas giants and so cannot host the bodies of water needed for life as we know it to survive. However, if Kepler-1625b-i "were to possess its own moon — a 'moon-moon' — that was Earth-like, this could potentially have been a habitable world," wrote Duncan Forgan at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland in findings in a recent study that has been submitted to the journal the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Specifically, Forgan calculated the habitable zone for Earth-size rocky bodies orbiting either Kepler-1625b-i or its host planet. He found that these bodies do not currently reside within a habitable zone but that they may have done so when their host star was younger. (The star has now consumed most of its hydrogen fuel and will likely eventually expand to become a red giant star, with its luminosity rising to levels that will generally destroy the habitability of any worlds there.)

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us