Soyuz Rocket's Launch-Abort Close Call Highlights Poor Space-Policy Decisions (Op-Ed)

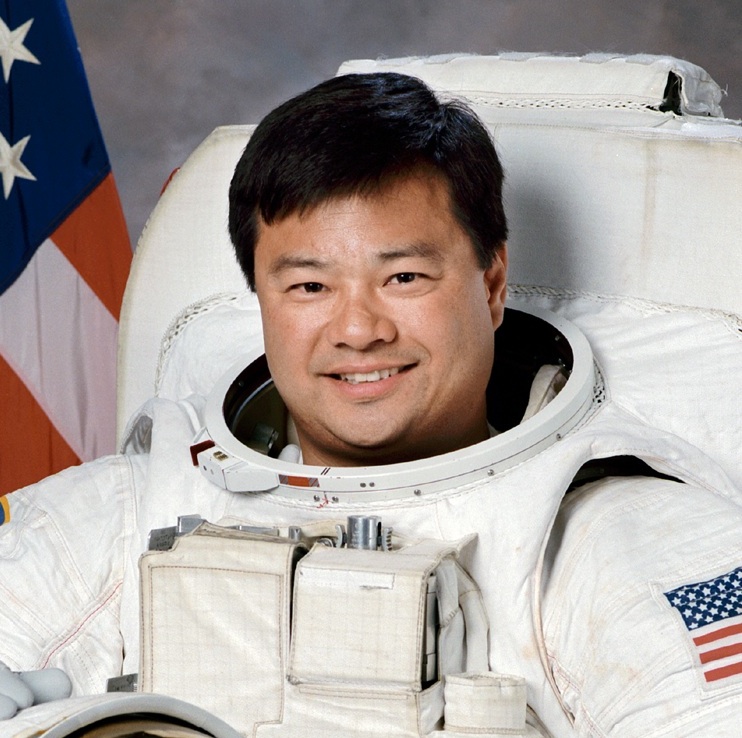

Leroy Chiao is the CEO and co-founder of OneOrbit LLC, a motivational, training and education company. He served as a NASA astronaut from 1990 to 2005 and flew four missions into space, as a crewmember aboard three space shuttles and as the co-pilot of one Russian Soyuz spacecraft launched to the International Space Station. After that flight, he served as the commander of the station's Expedition 10, a 6.5-month mission. Chiao has performed six spacewalks, in both U.S. and Russian spacesuits, and has logged a total of 229 days in space. Chiao contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

On Oct. 11, a Russian Soyuz MS-10 launched into a blue sky from the Baikonur Cosmodrome carrying a crew of two bound for the International Space Station (ISS). Everything was going well until just after first-stage separation, when observers saw a cloud of debris fall from the rocket. Moments later, a Russian flight controller announced that the booster had suffered a failure. The crew and the mission control team acted calmly and professionally, conducting a successful abort that led to a safe landing from which the crew walked away.

The Soyuz rocket will be grounded until the root cause of the failure is determined and a fix is put into place. It is unknown how long this process will take, but the clock is ticking. The Soyuz MS-09 spacecraft currently docked to ISS arrived in June of this year and has a 200-day certification life. So, the rocket must be cleared to fly before then; otherwise, we will face leaving the ISS without a crew on board.

Seven years ago, on Aug. 24, 2011, the launch of Progress 44P (also from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan) failed after the third stage of the Soyuz rocket carrying the freighter suffered its own failure. Pieces of the failed launch were recovered some 40 miles (64 kilometers) north of the Chinese/Siberian border in a wooded area. After that mishap, the Russians were able to complete their accident investigation and recertification efforts in time for the next crew to launch to ISS, thus avoiding leaving the station vacant.

Soon after both mishaps, news outlets quickly quoted NASA as saying that the events would have no significant immediate impact on the crew aboard the ISS. Those astronauts had adequate supplies and resources to continue their missions, NASA said. Although true, such statements miss the point. These two close calls highlight poor policy decisions.

If the ISS has to be left without a crew aboard, this could be a serious problem. That's because a number of events could cause the ISS to lose attitude control. Why is this important? When a structure like ISS loses this control, the object tumbles.

When there is a crew on board during these events, they run the procedures to re-establish control. This is not such a big deal. Without a crew however, the antennas would quickly lose a signal lock with mission control, and the ISS computers would fail to receive commands from the flight controllers. The solar arrays would no longer point at the sun correctly, and the storage batteries would run down. The ISS would slowly die.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It would not be possible to safely attempt a docking with a tumbling station, so a new crew would not be able to get aboard to rectify things. The ISS would slowly lose altitude and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere in an uncontrolled manner. We and our international partners would lose the 100-billion-dollar-plus facility. Large pieces would survive the re-entry and could cause significant damage upon hitting the Earth.

The big deal is the collective dependence of all ISS partner nations on the Soyuz rocket and spacecraft for carrying crew to and from the station, which has been the case since the end of the space shuttle program in 2011. The United States willfully and knowingly made this decision in 2004 under President George W. Bush’s administration after the Columbia shuttle accident.

President Barack Obama's administration confirmed that decision in 2009, rejecting an option in its space policy to continue flying the space shuttle through at least 2015. Both administrations pointed to rosy projections on when new U.S. vehicles might come online. Not surprisingly, all of these vehicles are still in development years after their projected dates. Russia and Canada made informal but public calls some years ago for bringing China and its Shenzhou spacecraft into the ISS program. However, certain powerful, Sino-phobic and arguably short-sighted members of the U.S. Congress blocked those proposals.

Under the current U.S. administration of President Donald Trump, the U.S. is supposedly heading back to the moon. However, as during the Obama administration, there is no program for accomplishing this. Without adequate yearly funding commitments, there could not and cannot be a program, then or now.

One of the cornerstones of the current space policy is to somehow "privatize" or "commercialize" the ISS by 2024-2025 and to use the "savings" from that privatization to help fund the program. The idea of operating the ISS profitably is so preposterous that I don't feel a need to comment further here. Besides, from where is the funding to come before 2024-2025?

What this look back shows is consistently poor policy decisions going back at least 14 years. What will happen to NASA and U.S. spaceflight in the coming years? I don't think anyone can say. The bright spots (and wild cards) are SpaceX and Blue Origin. Led by visionaries who have the resources and commitments to fund exploration and infrastructure development, these companies are building and launching hardware. They have plans to accelerate these activities around the Earth, the moon and even Mars.

There has been talk of NASA and the U.S. government partnering with these companies in bigger ways, to jointly explore space and build space infrastructure. I think this approach has real merit and possibilities. But the devil is in the details, and I will try to remain optimistic despite a disappointing 14 years and counting.

You can read more of Chiao's Expert Voices Op-Eds and film reviews on his Space.com landing page. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leroy Chiao is a former NASA astronaut and International Space Station (ISS) commander. Chiao holds appointments at Rice University and the Baylor College of Medicine. Chiao has worked extensively in both government and commercial space programs, and has held leadership positions in commercial ventures and NASA. Chiao is a fellow of the Explorers Club, and a member of the International Academy of Astronautics and the Committee of 100. Chiao also serves in various capacities to further space education. In his 15 years with NASA, Chiao logged more than 229 days in space, more than 36 hours spent in Extra-Vehicular Activity (spacewalks). From June to September 2009, he served as a member of the White House appointed Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee, and currently serves on the NASA Advisory Council. Chiao studied chemical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1983. He continued his studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, earning his Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in 1985 and 1987. Prior to joining NASA in 1990, he worked as a research engineer at Hexcel Corp. and then at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Livermore National Lab. Dr. Chiao left NASA in December, 2005 following a 15-year career with the agency. Chiao studied chemical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1983. He continued his studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, earning his Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in 1985 and 1987. Prior to joining NASA in 1990, he worked as a research engineer at Hexcel Corp. and then at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Livermore National Lab.