BepiColombo's Path: Why Does It Take So Long to Get to Mercury?

The European and Japanese space agencies launched their first mission to Mercury yesterday (Oct. 19, Oct. 20 GMT), but now, the mission's engineers and admirers have to endure a seven-year wait before the project's science begins in earnest.

The BepiColombo mission has such a long cruise time because it's actually really difficult to successfully orbit our tiniest planetary neighbor. It's so difficult that it took until 1985 before an engineer figured out any way to make the orbital trajectories work out properly.

The problem arises because Mercury is so small and so close to the sun. That means it orbits the sun incredibly quickly, and a spacecraft hoping to visit the innermost planet has to travel pedal-to-the-metal in order to catch up to the swift world. But there's a big catch: The sun's gravity will pull the spacecraft so strongly toward the star that a craft like BepiColombo actually needs to brake throughout its cruise to avoid getting tugged off course. [BepiColombo in Pictures: A Mercury Mission by Europe and Japan]

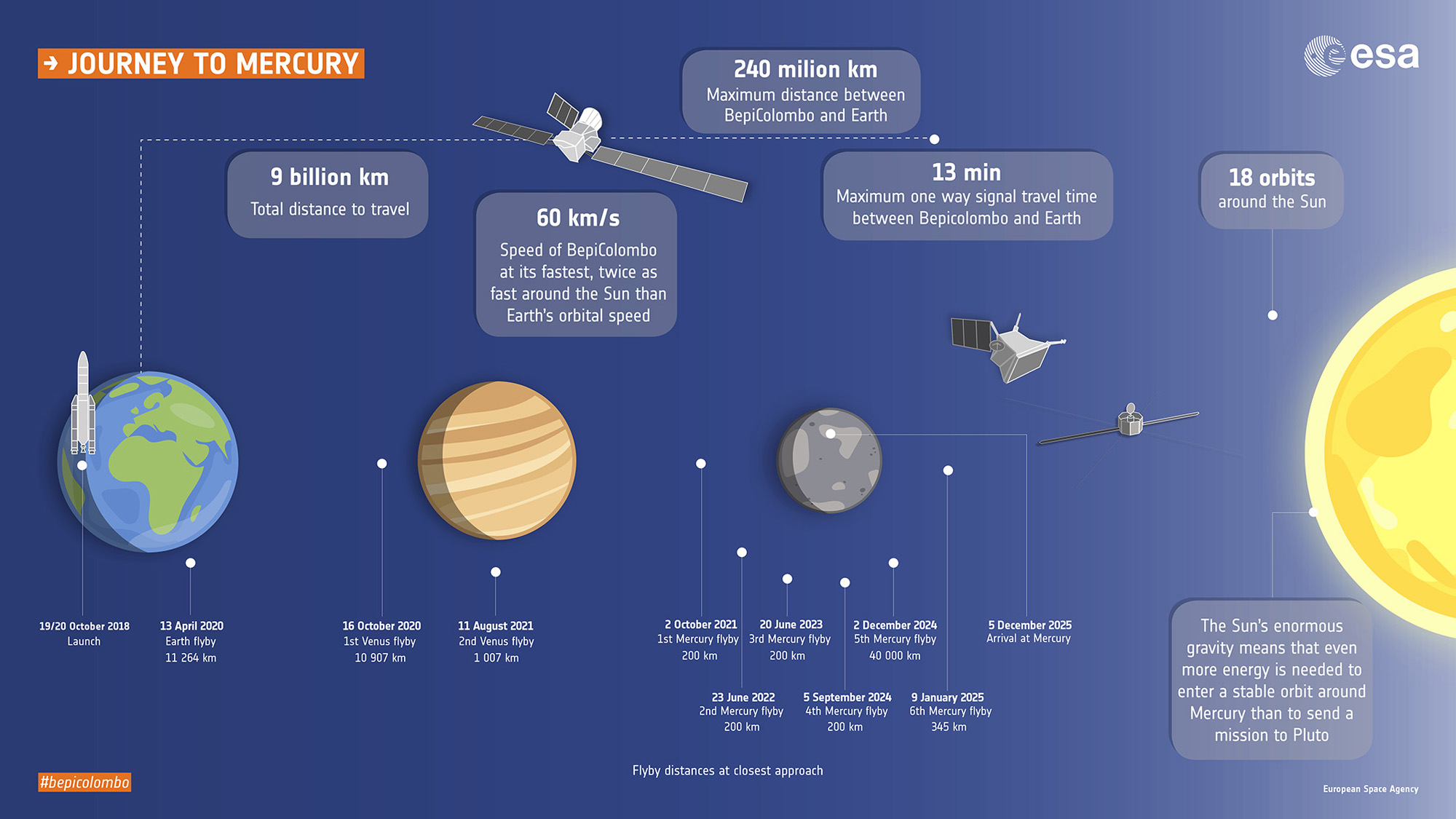

In order to tackle this dual challenge, BepiColombo's drivers have carefully devised a combination of solar power, chemical fuel and planetary flybys, which will work together to steer the spacecraft through this celestial obstacle course. All told, the spacecraft will expend more energy than it would trying to reach Pluto, which resides over near the edge of the solar system. But those planetary flybys will bring BepiColombo's cruise time to a total of just over seven years.

The mission's series of flybys — one of Earth in April of 2020, two of Venus in 2020 and 2021, and six of Mercury itself between 2021 and 2025 — will each tweak the spacecraft's orbit just a little, nudging it closer and closer to the mission's target. These flybys will also give engineers a chance to make sure many of the instruments on board BepiColombo are working as they should be, because more than half of them will be turned on.

Then, in December of 2025, BepiColombo will slip into orbit around the tiny planet. Once the probe does so, it will separate into the two science spacecraft that are currently joined together for the long ride: Europe's Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Japan's Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO). Those two spacecraft will fly in complementary orbits, with the MPO circling the planet every 2.3 hours and MMO doing so every 9.3 hours.

If everything goes according to scientists' plans, those careful twirls will let the 16 instruments that make up BepiColombo gather plenty of eyebrow-raising data about tiny, strange Mercury and how our entire solar system came to be.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.