Asteroid or Comet? Weird Blue Space Rock 'Phaethon' Gets a Close-Up

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — A bizarre, blue asteroid that acts like a comet and appears to be responsible for the annual Geminid meteor shower made a close flyby of Earth last year, giving astronomers an opportunity to study the object in unprecedented detail. They found that the asteroid is even weirder than they had imagined.

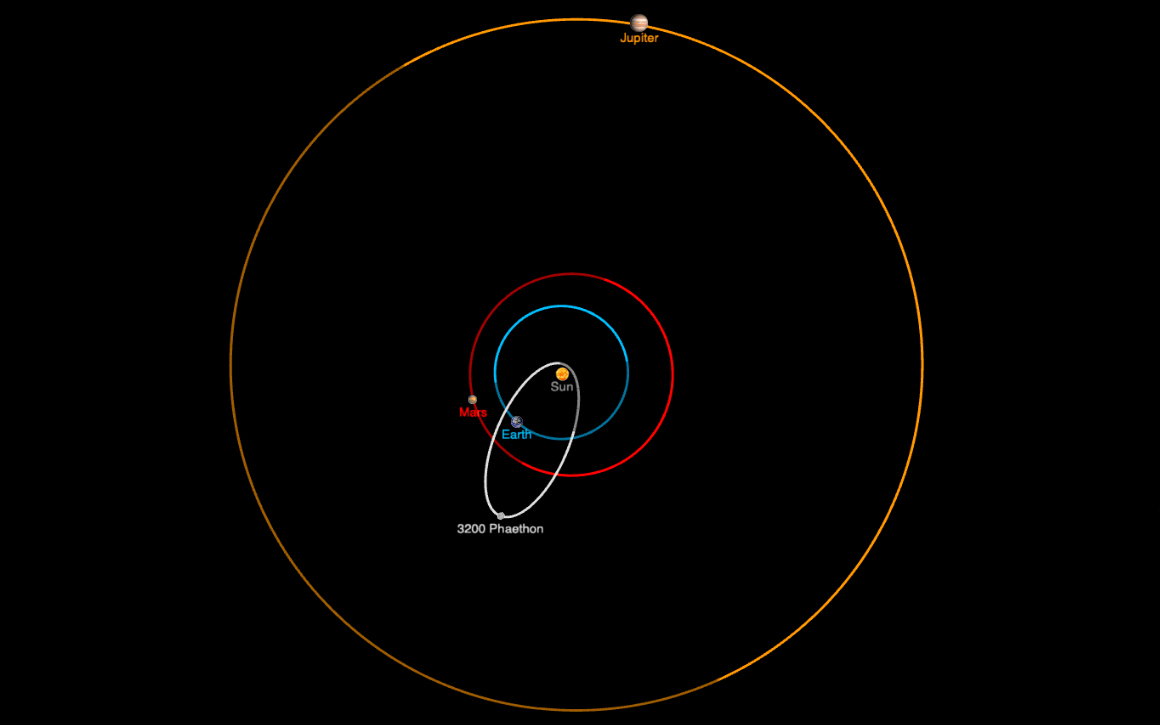

Asteroid 3200 Phaethon is a special space rock with a rare blue color and an extremely eccentric orbit that has the object pass superclose to the sun and then out past the orbit of Mars. One orbit takes about 1.4 Earth years. This kind of orbit is more typical for comets than asteroids.

But while Phaethon acts like a comet, it doesn't look like one. When comets get close to the sun, they form a cloud known as a "coma" and a long tail of dust and gas. Phaethon, however, always looks like a tiny speck floating through space. [The 7 Strangest Asteroids in the Solar System]

On Dec. 16, 2017, the asteroid Phaethon made its closest approach to Earth since 1974, passing within 6.4 million miles (10.3 million kilometers) of our planet. While backyard astronomers pointed their telescopes toward the space rock to catch a glimpse of the historic flyby, astronomers in observatories around the world took the opportunity to learn more about what the object is and where it came from.

Teddy Kareta, a graduate student at the University of Arizona who led an international effort to investigate Phaethon during the flyby, presented his team's findings here at the 50th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences today (Oct. 23). Kareta and his colleagues observed Phaethon's close approach using NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea in Hawaii and the Tillinghast telescope on Mount Hopkins in Arizona.

One of their findings may overturn the current prevailing theory about the origin of Phaethon. Astronomers have long suspected that Phaethon is a fragment of the much larger blue asteroid Pallas. "However, Pallas' albedo [or reflectivity] is about twice what we found for Phaethon's albedo," Kareta said. With an albedo of about 8 percent, Phaethon is slightly brighter than charcoal and only about half as bright as Pallas, Kareta said.

The researchers also found that the surface of Phaethon is equally blue all around, which means that the object has been "evenly scorched" or "cooked" by the sun's heat. Phaethon's blue color indicates that the rock has undergone intense heating, Kareta said. During Phaethon's trips around the sun, it gets heated to temperatures of up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit (800 degrees Celsius), which is "so hot that metals on the surface turn to goo," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Creating the Geminid meteor shower

The Geminid meteor shower, which arrives every year in December, is the only meteor shower that appears to have originated from anything other than a comet. Comets are icy bodies containing a mixture of ice, rock, dust and frozen gas. When a comet gets close to the sun, some of this material gets vaporized and small pieces of the comet break loose, leaving behind a trail of comet crumbs in space. When Earth passes through such a trail of debris, we get meteor showers.

Asteroids like Phaethon are rocky objects that don't behave the same way as comets do when they get close to the sun, and astronomers aren't sure how Phaethon could have created the Geminids. Before Phaethon was discovered, in 1983, astronomers had no idea where the Geminids came from. Having observed that Phaethon's orbit matched the trail of debris that causes the annual meteor shower, though, astronomers determined that Phaethon must be the source.

Exactly how Phaethon created that trail of debris remains a mystery, Kareta said. While it is possible that material swept off the asteroid's surface could contribute to the debris, "the amount of dust that gets swept off is nowhere near enough to sustain the Geminids," he said. One possibility is that Phaethon collided with another object in space and the Geminids are the debris from that "catastrophic breakup," he said. "So, in that case, you're essentially seeing dust, which is kind of like blood splatter, to be gruesome, from this really violent event."

Another possibility is that Phaethon is a dormant comet, or a comet that turned into an asteroid over time. "If it was cometary at some point in the past, maybe it made the meteor shower the normal way and left behind those comet crumbs … but since then, it's been cooked through and turned off and it just looks like a rock," Kareta said.

Phaethon may look more like an asteroid than a comet, but it displays qualities of both types of objects. It doesn't have the coma and tail that are characteristic of comets, but it does release "a tiny dust tail when it gets closest to the sun in a process that is thought to be similar to a dry riverbed cracking in the afternoon heat," University of Arizona officials said in a statement. "This kind of activity has only been seen on two objects in the entire solar system — Phaeton and one other, similar object that appears to blur the line traditionally thought to set comets and asteroids apart."

A mission to Phaethon: DESTINY+

Findings from this new research will come in handy for scientists with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), which is currently planning a mission to Phaethon. The mission is called DESTINY+ (an abbreviation for Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary Voyage, Phaethon Fyby and Dust Science), and it is currently scheduled to launch in 2022.

DESTINY+ will fly by Phaethon and other near-Earth objects to study how dust is ejected from these objects. This should help to explain Phaethon's tiny dust tail. DESTINY+ could help scientists figure out whether Phaethon is an asteroid, a comet or something else. "It's probably somewhere in the middle," Kareta said.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.