'It's Going to Be Historic': New Horizons Team Prepares for Epic Flyby of Ultima Thule

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — In less than 10 weeks, NASA's New Horizons mission will explore the most distant target ever visited by a spacecraft.

In the early-morning hours of Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons will ring in the New Year by flying past the Kuiper Belt object (KBO) officially called 2014 MU69 but nicknamed Ultima Thule, a city-size rock regarded as a frozen relic from the birth of the solar system.

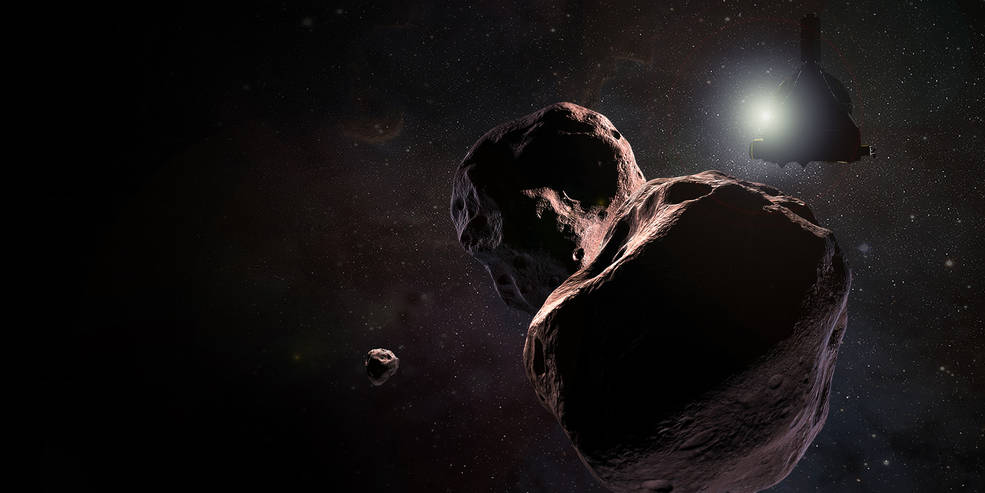

Although scientists have a rough size estimate for Ultima Thule — about 23 miles (37 kilometers) wide — they don't have much more information. They aren't sure if it's elongated, if it has a moon or ring system or even if it's a single object. Indeed, some of the very limited observations of Ultima Thule suggest it might actually be two close-orbiting bodies. [NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

"Really, we have no idea what to expect," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said during a news conference here yesterday (Oct. 24) at the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences meeting.

But New Horizons should reveal Ultima Thule's secrets, just as the probe lifted the veil on Pluto during its historic flyby of the dwarf planet in July 2015.

Not only will New Horizons reveal insights about the size, surface and possible orbital companions of Ultima Thule, it should also help planetary scientists understand how the solar system formed, Stern said.

"Whatever we do, it's going to be historic," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

'A dot in the distance'

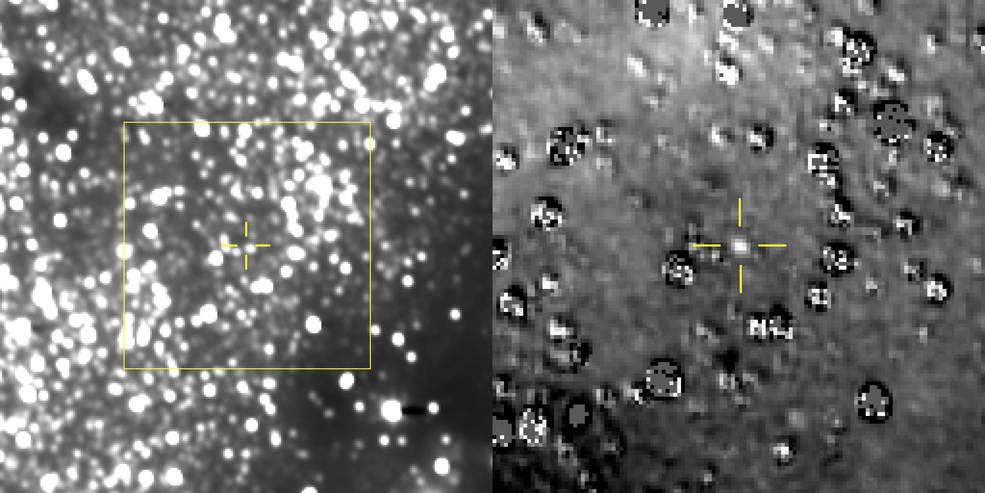

New Horizons' imagery as it approached Pluto more than three years ago revealed more and more detail about the distant dwarf planet. But don't expect the same thing to happen with Ultima Thule, which is much smaller than the 1,477-mile-wide (2,377 km) Pluto.

"Ten weeks out from Pluto, we could already resolve the disk. Each week, we waited to see more and more detail," Stern said. "But Ultima Thule 10 weeks out is just a dot in the distance, and it will remain a dot in the distance until literally the day before the flyby, when we start to resolve it."

New Horizons will get a relatively brief look at Ultima Thule on Jan. 1, zooming by the frigid world at 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h). But scientists will wring as much as they can out of the encounter.All seven of New Horizons' science instruments will scrutinize the KBO, probing its surface for hints about its composition or signs of cometary activity. A high-resolution camera will explore the surface, and the spacecraft will measure Ultima Thule's rotational properties.

After New Horizons visited Pluto, the probe snoozed for a bit. But the clock started in earnest again in June 2018, when the spacecraft's particle-detecting instruments began to make observations. The team has also begun conducting operational readiness tests to ensure the spacecraft is prepared for the New Year's Day flyby.

By late November and early December, "we'll be making very intensive observations of the environment around Ultima Thule," Hal Weaver, a New Horizons team member at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), said during yesterday's news conference.

Those lead-up observations will hunt for moons, dust or debris rings that could harm the spacecraft during its flyby. The team has until Dec. 16 to decide whether to make the close flyby they are hoping for (2,175 miles, or 3,500 km from the object's surface) or buzz Thule from a safer distance (6,200 miles, or 10,000 km), Weaver said. [Kuiper Belt Objects: Facts about the Kuiper Belt & KBOs]

For perspective, New Horizons got within 7,800 miles (12,500 km) of Pluto in July 2015.

"We can still have a fantastic mission but avoid damage to the spacecraft," Weaver said.

The final images that New Horizons beams home before the close encounter will be comparable to the glimpse NASA's Hubble Space Telescope currently can catch of Pluto, Weaver said — an image only a handful of pixels across.

"Wait until afterwards — that's when the real rich dataset is going to come down," he said.

Once the spacecraft spins to point its instruments at Ultima Thule, New Horizons won't be able to communicate with Earth. And the probe will continue studying the KBO for a spell after closest approach, staying locked on to measure the object's nighttime temperatures, which can reveal information about how heat travels through its surface. Plasma and dust sensors will also measure the environment immediately surrounding Ultima Thule.

Stern and his colleagues don't expect to see an atmosphere or any sign of current geological processes from the tiny rock, but he says they will look regardless.

"If we find recent activity in an object this small, that would be very large-point headlines, because we would not understand how that could happen," Stern said.

Several hours after the close encounter, the probe will rotate and send home a signal to let its fans on Earth know that it survived its brush with Ultima Thule. The signal will take over 6 hours to reach mission control, mission team members said.

On Jan. 2 and Jan. 3, New Horizons will return some of the best images and measurements from the flyby. The photos will feature even greater resolution than the ones the spacecraft took of Pluto, mission team members said. [Pluto Flyby Anniversary: The Most Amazing Photos from NASA's New Horizons]

It took New Horizons about 16 months to return all the data from the Pluto encounter. Getting all the Ultima Thule images on the ground will take even longer.

"Data will be coming down through all of 2019 and most of 2020," Stern said.

The spacecraft will transmit the 50 gigabits of data it collects during the flyby at a little more than 1,000 bits per second. Fellow New Horizons scientist Carey Lisse, also of APL, compared it to the old days of dial-up, where images would load row by row.

"Except you weren't dialing up from 4 billion miles away," Stern said.

'Far out'

Stern said "Ultima Thule" is Latin for "beyond the farthest frontiers," and the icy rock certainly is that. Not only does it lie farther away than any cosmic object ever explored — more than 40 times farther from the sun than Earth orbits — it also will be the first object studied deep inside the Kuiper Belt.

"This will be our first ground truth, our first close look at what makes these [Kuiper Belt] objects dark and red," New Horizons team member Kelsi Singer, also of SWRI, said during yesterday's news conference. "That will be important for understanding these objects."

Understanding the ices at the edge of the solar system will tell us a surprising amount about our own world. The Kuiper Belt holds the material leftover after planet formation ended. By studying Ultima Thule, we'll get a glimpse into the same ingredients that helped to build Earth and its siblings, Stern said.

"New Horizons is going to have the capability in the space of one week, the first week of January 2019, to confirm or refute the very models [of solar system formation] presented here at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting," Stern said.

The flyby should also help to resolve a mystery about the KBO's surprising brightness. Like most rocky objects in the outer solar system, Ultima Thule is nearly as dark as coal, despite its icy shell. That's because it has been baked by cosmic radiation for eons, Lisse said. But Ultima Thule is a little bit brighter than it should be.

"There's something going on that makes it twice as bright as your average comet nuclei," Lisse said. Hopefully, New Horizons will uncover what makes the tiny target shine.

Right now, the scientists still aren't certain what New Horizons will reveal when it races past Ultima Thule in only a few weeks. But they are looking forward to unveiling the secrets of the solar system.

"There's one thing you can say about Ultima Thule for sure," Stern said. "It's far out."

Editor's Note: This article was corrected to reflect that a signal from the spacecraft at Ultima Thule will take over 6 hours to reach Earth; it would take over 12 hours for a round-trip communication. Also, it will transmit 50 gigabits, not gigabytes.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd