Tweeting from Space? How 280 Characters Can Change Astronaut Psychology

It turns out that when you tell astronauts that a psychologist has been using linguistic analysis tools on tweets sent from space, they get a little sensitive. "That concerns me, as I'm a test pilot and math major," Randy Bresnik, NASA astronaut and assistant to the chief of the astronaut office, said jokingly.

So far at least, Bresnik's own tweets haven't gone under the microscope, but researchers really are taking to Twitter hoping to pick up subtle linguistic cues they can use to understand how space travel affects astronauts psychologically.

"Usually you're not going to hear the raw emotion," Sara Ahmadian, a graduate student in counseling at the University of British Columbia in Canada and lead researcher on the project, told Space.com. "But the idea is that the thoughts behind or the context behind those tweets still comes from the astronaut themselves, so even when people try to conceal their emotions, our words sort of give us away." [NASA's Best Earth-from-Space Photos by Astronauts in 2017 (Gallery)]

Specifically, Ahmadian and her colleagues scanned 13 astronauts' tweets for words that conveyed positive or negative emotions and those that referred to friends and family. Then, they looked for changes over time as they followed those astronauts through launch preparation, their visit to the International Space Station, and their first six months back on Earth.

Bresnick started tweeting when he got assigned to his space station flight because he thought it would be a good way to share his experience on the orbiting laboratory with those of us on the ground. He said it took some time to get used to Twitter and its unique constraints. "It's like learning another — a shorter language — but adding another language to the many skills: OK, you've got your Twitter language," he said.

Ahmadian said the research, which she presented on Oct. 1 at the International Astronautical Congress held in Bremen, Germany, is still preliminary. Thirteen astronauts aren't all that many, and there are plenty of ways to fool the analytics program, for example by referring to friends by name rather than by using a general noun the program can recognize.

But she still thinks that the trends the team is noticing are intriguing. She says they see a decrease in social terms while astronauts are in space and an increase in positive emotion words after they return. That makes some sense, former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino, who was the first astronaut to compose tweets from space (although at the time they had to be emailed to Earth and posted by the ground crew), told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

He said astronauts are thinking about their terrestrial communities but experiencing isolation, and they're focused on work. "It's not all fun and games and you're up there concentrating," he said. "We were so busy all the time, there really wasn't much downtime." (Massimino joked about not tweeting during the period he was doing five consecutive spacewalks to tend to the Hubble Space Telescope because he didn't want to have to tweet that he had broken it.)

But after returning to Earth, astronauts tend to use significantly more positive words in their tweets, Ahmadian said. She thinks that shows how rewarding an experience space travel is and parallels other research that has shown astronauts tend to develop a whole-Earth perspective on their return. [The Best Astronaut Selfies in Space]

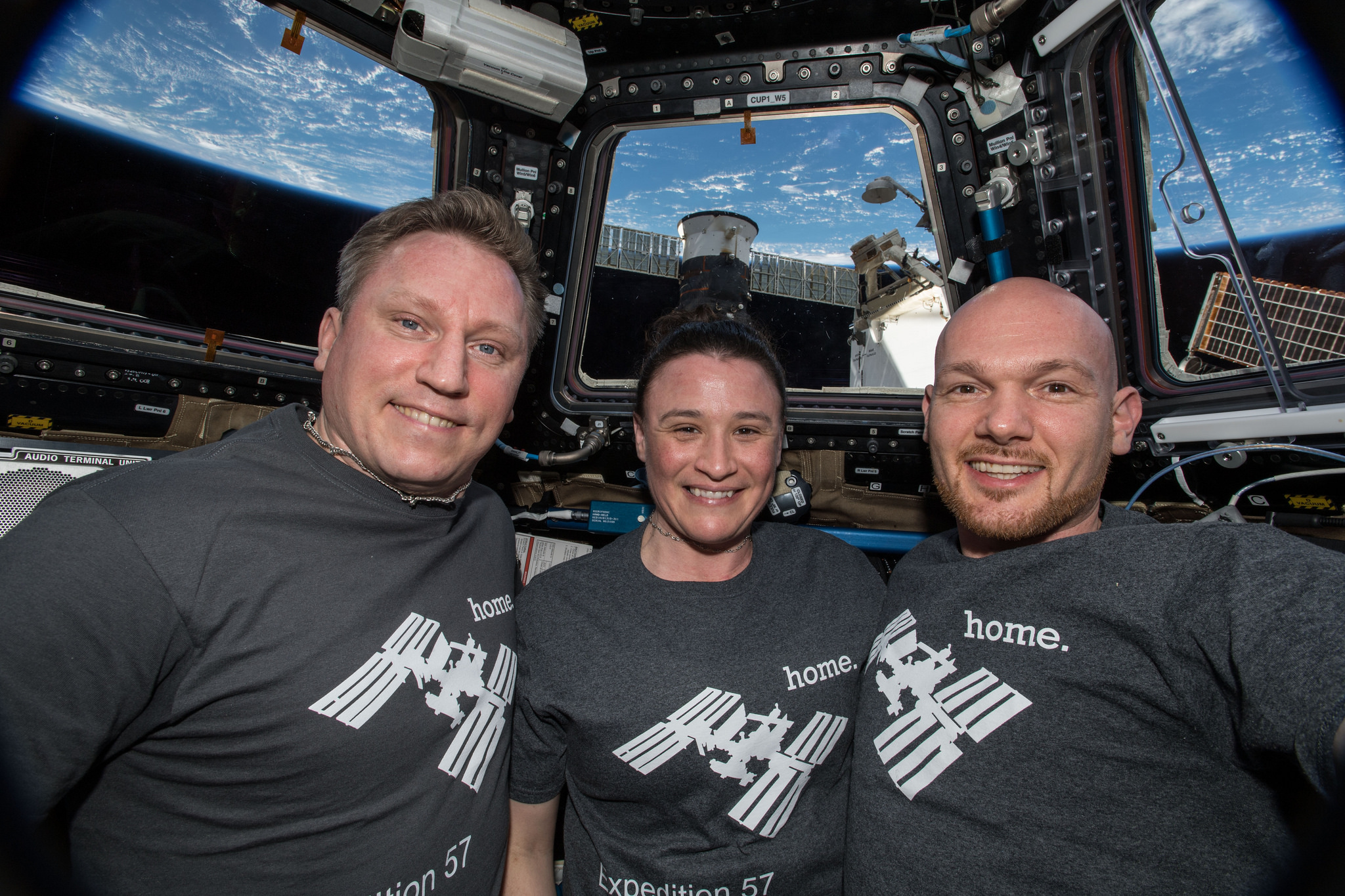

Although the analysis sticks to words for now, another characteristic that has stood out to Ahmadian is how many photographs of Earth astronauts share during their time in space. (Massimino said this may just reflect the arrangement of windows on the space station and the difficulty of taking good photographs of the stars, which he said he loved to watch.)

Ahmadian says studying astronaut tweets and photographs isn't just a matter of curiosity: They may be important to consider when space agencies look beyond near Earth orbit, when home is farther away and astronauts are gone for longer. They won't even be able to see the blue marble out their window. "How is that going to affect them?" Ahmadian said. "Maybe a lot of these positive emotions is coming from the fact that you can see Earth, it's right there, you can see how beautiful it is."

And the isolation Ahmadian sees in astronaut tweets will likely only worsen as well as space voyages lengthen. "Even if we take the most well-adjusted individuals and put them in space, we are putting them in a situation that is very different from anything that we could capture on Earth, even with analog environments," Ahmadian said. "Clearly, it's not just about selecting the best people, it's also about looking at what could happen up there and also looking at the positive impact that going into space has; I think that's something that has been completely ignored."

Both Bresnik and Massimino consider it their job back on Earth to share their own life-changing experiences in space, they said. But maybe not by overthinking their 280-character messages.

"Some people come up with a lot of really important statements and try to change the world," Massimino said. "That requires too much thinking for me."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.