'War of the Worlds' Radio Broadcast Terrified Listeners 80 Years Ago. Would E.T. Contact Cause Panic Today?

On this day (Oct. 30) 80 years ago, actor Orson Welles announced to audiences in a chilling radio performance that Martians were invading New Jersey, leading terrified listeners to believe that Earth was under attack by hostile aliens.

But the so-called news was fake. Welles' infamous broadcast was a dramatization of the H.G. Wells science-fiction classic, "The War of the Worlds," and was part of a weekly series of dramatic broadcasts created in collaboration with the Mercury Theatre on the Air for CBS, according to a transcript of the broadcast.

Thanks to decades of space research, understanding of extraterrestrial life has come a long way since Welles' radio play, and it's generally understood that Mars isn't home to an advanced alien civilization with lethal weaponry and spacecraft. Public fascination with extraterrestrials still runs high; however, a modern announcement about alien creatures would likely spur a very different response today than "The War of the Worlds" did in 1938, experts told Live Science. [9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why We Haven't Found Aliens Yet]

During the radio transmission, an actor posing as a news announcer interrupted a scheduled music performance. With a tone of rising alarm, he described telescope observations of "three explosions" on Mars, then brought in on-the-scene reporting from Grover's Mill, a town near Princeton, New Jersey. As the drama unfolded, performers posing as witnesses described unidentified flying objects (UFOs) and "strange creatures" firing a futuristic heat ray that had killed dozens of people.

Listen to the full broadcast here, courtesy of Archive.org:

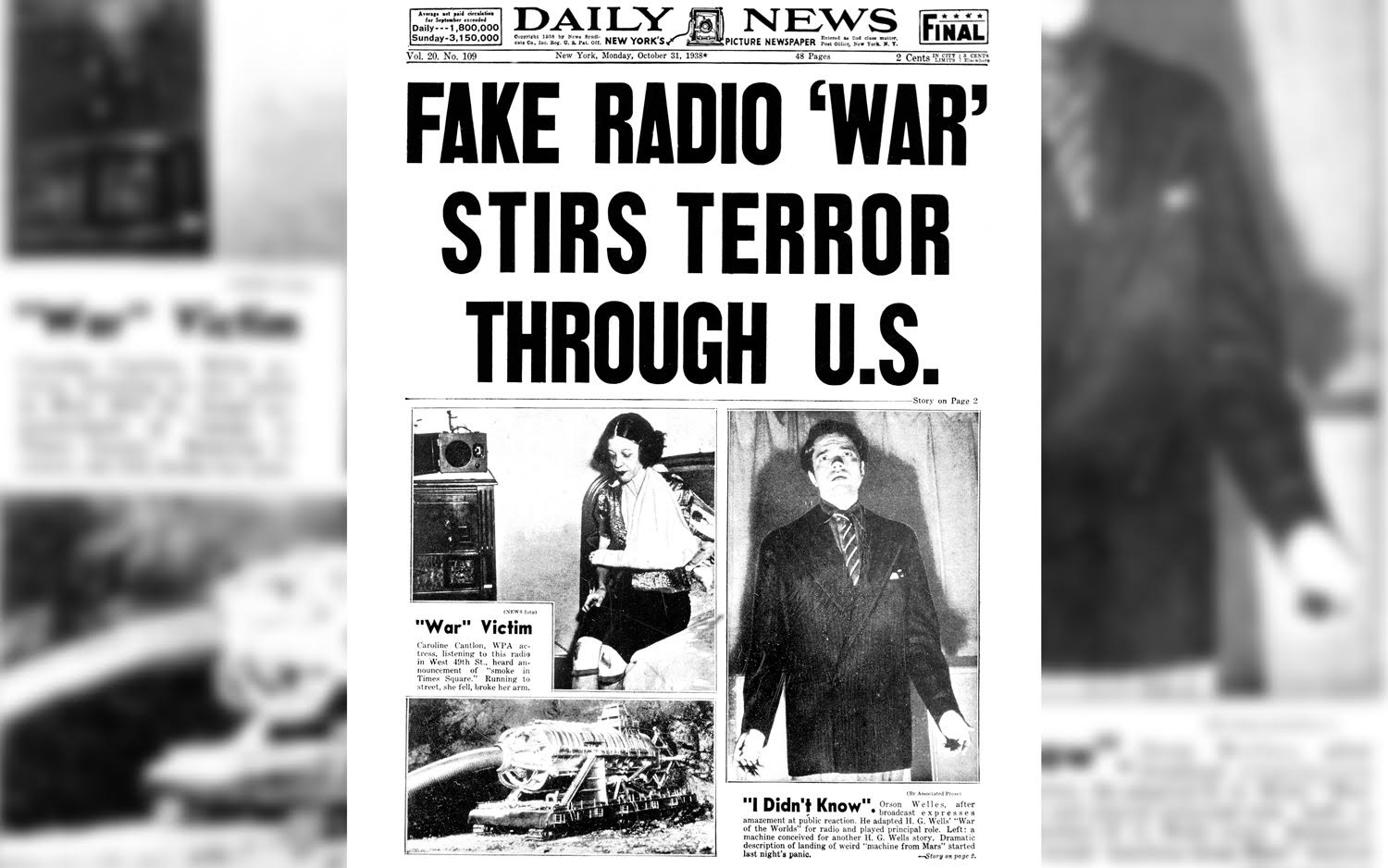

Though the program was peppered with reminders that it was theatrical, many people who tuned in thought that the alien invasion was real, and breathless newspaper headlines later described widespread panic caused by the prospect of an alien invasion.

"Thousands of listeners rushed from their homes in New York and New Jersey, many with towels across their faces to protect themselves from the 'gas' which the invader was supposed to be spewing forth," the Daily News reported the next day.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While radio listeners may have fallen for the tale of a Martian invasion, space scientists of the day were already well aware that Mars wasn't capable of harboring a thriving civilization of intelligent aliens, Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer with the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute (SETI) in California, told Live Science.

"Certainly, by the late 1930s, no one believed it.There was increasing knowledge from astronomers: Mars has a very thin atmosphere; there's not much oxygen; we don't see any liquid water on the surface," Shostak said. All this suggested that if we did have intelligent cosmic company in the universe, it wasn't on Mars — or even in our solar system, he explained.

In fact, the violent episode Welles described is by far the least likely scenario for how humans might first encounter extraterrestrial life, according to science writer Michael Wall, author of "Out There: A Scientific Guide to Alien Life, Antimatter and Human Space Travel (For the Cosmically Curious)" (Grand Central Publishing, Nov. 11, 2018). [The "War of the Worlds" Radio Broadcast Explained]

Alien microbes, not alien monsters

A militaristic alien attack would involve extraterrestrials that are not only intelligent and technically advanced, but who also know that humans exist and can travel to our solar system, Wall told Live Science. An improbable number of variables would have to fall into place for that to happen. A stronger possibility is that our first encounter with alien life will be through finding microbes from other worlds, which are far more likely to be common across all the cosmos than intelligent organisms, said Wall, who is a senior writer at Live Science's sister site Space.com.

Today, an announcement about discovering extraterrestrial microbes is far more likely to promote fascination than panic, he said.

"With all the news about exoplanets [planets outside our solar system], people are primed for this," Wall said. "Those who are paying attention know how much habitable real estate is out there. And it just makes sense that if there's something out there that it'd be microbial."

However, even though microbes may well be the first "aliens" that we'll encounter, that doesn't rule out the possibility of detecting intelligent extraterrestrial communications, Shostak told Live Science. [Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us]

Eavesdropping on aliens

SETI scans the skies daily for radio signals that might be produced by forms of intelligent life. And even though there's probably far less intelligent life in the universe than there is microbial life, intelligent extraterrestrials could potentially broadcast their presence over much greater distances.

"Microbes can make oxygen in the atmosphere. But intelligent life could make giant lasers or radio transmitters, so you might be able to hear them from farther away," Shostak said.

One way we might find distant aliens is through detection of their radio signals, the subject of SETI's tireless searches using the Allen Telescope Array at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory in California. But SETI is also building equipment to search for possible extraterrestrial signals produced by laser beams, Shostak said.

Of course, finding these signals requires that purported intelligent aliens are aiming them in our general direction. Nevertheless, Shostak is confident that one of these signals will be detected sooner than you think.

"I bet a lot of people a cup of coffee that we'll find something within two dozen years," Shostak said. "And that's because equipment is getting better and better."

A first meeting with E.T. via microbes or faraway signal transmissions would certainly be a lot less frightening than hearing about weapon-toting, tentacled creatures setting fire to our cities. After the broadcast, Welles claimed that he had no idea people would take the program so seriously; he issued an apology saying "it was a terribly shocking experience to realize that I had caused such widespread terror," The Daily Princetonian reported on Nov. 1, 1938.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.