Mars Attacks! Halloween 1938 and the Infamous 'War of the Worlds' Radio Broadcast

From Edgar Rice Burroughs' "John Carter of Mars" to Ray Bradbury's "The Martian Chronicles" all the way to the present day with Andy Weir's "The Martian," science fiction has speculated about what secrets the Red Planet possesses. However, "The War of the Worlds" is probably the best-known illustration of humans' long-held fascination with our nearest planetary neighbor.

The modern myths surrounding Mars originated with Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli's discovery of "canali," or channels on the planet's surface, in 1877. After his observations were mistranslated into English as "canals," they caused widespread speculation that these were artificial waterways built by an advanced civilization. In reality, they were random surface features that formed into lines when viewed through a certain type of lens.

Just 20 years later, English author H.G. Wells wrote "The War of the Worlds," a story written in the first person about a man and his brother struggling to stay alive as Martians invade South East England. It was one of the earliest stories to detail a conflict between humankind and an alien race, and it changed science fiction forever. [Listen to the 'War of the Worlds' Radio Broadcast!]

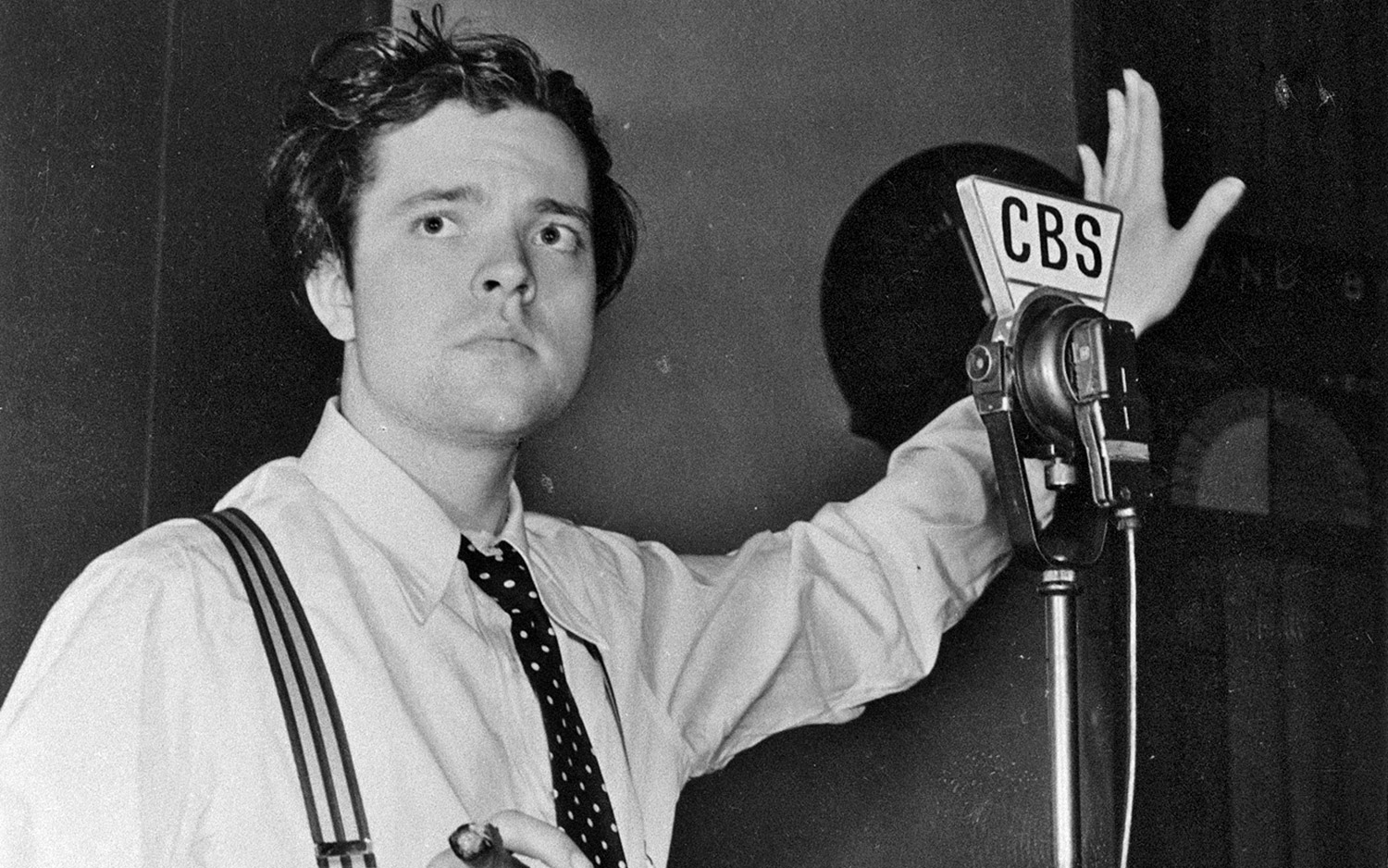

Forty years after the story's publication, in 1938, up-and-coming writer/actor/director/producer Orson Welles was on the lookout for new ideas and innovative ways to tell dramatic stories for his "Mercury Theater on the Air" shows that were broadcast by CBS from Radio City in New York.

Welles' program "Mercury Theater on the Air" was a low-budget weekly show without a sponsor, according to a story on "War of the Worlds" in Smithsonian magazine. It had been on the air at CBS for 17 weeks and had steadily built a small but loyal audience by running modern adaptations of well-known literary classics…but for the week of Halloween, Welles wanted something different.

He discussed his fake newscast idea with producer John Houseman and associate producer Paul Stewart, and together they decided to adapt a work of science fiction. They considered "The Purple Cloud" by M.P. Shiel and "The Lost World" by Arthur Conan Doyle before eventually purchasing the radio rights to "The War of the Worlds."

The novel was adapted for radio by playwright and screenwriter Howard Koch, who changed the setting from 19th-century England to modern-day U.S., with the first Martian spacecraft landing in rural Grover's Mill, New Jersey.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The program's format was a simulated, live broadcast of unfolding events in the form of news bulletins interrupting a scheduled program of dance music. ['Alien Invasion' Radio Broadcast Terrified Listeners 80 Years Ago]

"I had conceived the idea of doing a radio broadcast in such a manner that a crisis would actually seem to be happening," Welles later said, according to the Smithsonian story, "and would be broadcast in such a dramatized form as to appear to be a real event taking place at that time, rather than a mere radio play."

Koch struggled to make the script interesting at first, and Welles stressed the importance of inserting news flashes and eyewitness accounts to create a sense of urgency and excitement. The cast and crew also offered suggestions and their own contributions, according to the Smithsonian story — for instance, to create the role of reporter Carl Phillips, actor Frank Readick went to the record library and played the recording of Herbert Morrison's radio report of the Hindenburg disaster over and over.

At 8 p.m. ET on Sunday, Oct. 30, 1938, the show aired. It began as a simulation of a normal evening broadcast featuring a weather report and music by "Ramon Raquello and his Orchestra live from the Meridian Room in the Hotel Park Plaza in downtown New York."

After a few minutes, the music begins to be interrupted by several news flashes about strange gaseous explosions seen on Mars through telescopes on Earth.

Reporter Carl Phillips (Readick) interviews Princeton-based astronomy professor Richard Pierson (played by Welles), who dismisses speculation about any life on Mars. The musical program returns, but is interrupted once again by news of a strange meteorite landing in Grover's Mill. Phillips and Pierson are dispatched to the site, where a large crowd has gathered.

Philips describes the chaotic atmosphere around the strange cylindrical object, and Pierson admits that he does not know exactly what it is, but that it seems to be made of an extraterrestrial material. The cylinder unscrews and Phillips describes the horrific, tentacled monster that emerges from inside.

Police officers approach the Martian waving a flag of truce, but the invaders respond by firing a heat ray, which incinerates the group and ignites the nearby woods and cars as the crowd screams and attempts to flee. Phillips' shouts about incoming flames are cut off midsentence, and after a moment of silence, an announcer explains that the remote broadcast was interrupted due to "some difficulty with our field transmission." [Best Space Movies in the Universe]

After a brief musical interlude, the regular programming begins to break down as the studio appears to struggle with incoming casualty and firefighting updates. The audience hears that the New Jersey state militia has declared martial law and attempted to attack the cylinder. A Martian tripod rises from the pit and disintegrates the military forces gathered there. From here, it only gets worse as reports flood the studio newsroom of massive destruction and fleeing refugees clogging the highways in a beautifully orchestrated crescendo of chaos.

Much of New Jersey is now in flames. Eventually, a news reporter, broadcasting from the roof of the studio building in Manhattan, describes the Martian invasion of New York City. Buildings are burning and people everywhere are dying. He reads one last bulletin stating that Martian cylinders have fallen all over the U.S., then describes a cloud of poisonous smoke slowly moving down the street until he coughs, chokes and falls silent, leaving only the sounds of the city under attack in the background.

After a period of silence comes the voice of announcer Dan Seymour: "You are listening to a CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the 'Mercury Theatre on the Air,' in an original dramatization of 'The War of the Worlds' by H.G. Wells. The performance will continue after a brief intermission."

After a short break, the program shifted to a more conventional radio drama format and followed a survivor dealing with the aftermath of the invasion and ultimately discovering that the Martians were defeated by microbes rather than by humans, thus returning a little more to the original source material.

Despite the same announcer clearly saying at the beginning of the program "The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the 'Mercury Theatre on the Air' in 'The War of the Worlds' by H.G. Wells" and the program even being listed as such in the newspaper radio guide, by 8:32 p.m. — a little over halfway through the show — executives at CBS began to hear that widespread panic was spreading through the suburbs of New York and New Jersey.

Many listeners heard only a portion of the broadcast and mistook it for a genuine news broadcast. Anxiety levels were a little higher than usual across the U.S. at this time because of the growing political tensions in Europe. Consequently, this horrific alien invasion tapped into the slowly rising fear and paranoia of many.

Thousands rushed to share the false reports with others or called CBS, newspapers, or the police to ask if the broadcast was real.

The illusion of realism was reinforced because the "Mercury Theatre on the Air" was a sustaining show without commercial interruptions, and the first break in the program came some 30 minutes after the introduction. Popular legend holds that some of the radio audience may have been listening to "The Chase and Sanborn Hour with Edgar Bergen" and tuned in to "The War of the Worlds" during a musical interlude, thereby missing the clear introduction that the show was a dramatic production. [The "War of the Worlds" Radio Broadcast Explained]

By the next morning, the name and face of the 23-year-old Welles were on the front pages of newspapers on both coasts, along with headlines about the mass panic his CBS broadcast had allegedly inspired. In retrospect, the hysteria is now considered to be have been exaggerated by the media, but regardless, it still gave a pretty good Halloween scare to a lot of people in the tristate area.

As for Welles himself, despite a pretty intense grilling from the press and even calls for new rules for broadcast to be enforced by the FCC, his reputation as a storyteller and artist were forever secured in the annals of history.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

When Scott's application to the NASA astronaut training program was turned down, he was naturally upset...as any 6-year-old boy would be. He chose instead to write as much as he possibly could about science, technology and space exploration. He graduated from The University of Coventry and received his training on Fleet Street in London. He still hopes to be the first journalist in space.

With 70% off, this Apple TV+ offer is one of the best streaming deals I've ever seen — watch all episodes of "Severance" and much, much more for just $2.99 a month

We finally have a release date for ‘The Alters’, the sci-fi survival game where you team up with your clones to survive a planet on fire (video)