Monster Rifts in Comet Tails Are Sculpted By the Sun

Scientists are one step closer to understanding why some comets have strange dust bands in their tails. The main culprit in this cosmic mystery? Our own sun.

Comets are small bodies of ice and dust left over from when the solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago. As comets get close to the sun, the sun's heat unlocks trapped gases in those comets, in the process also releasing dust, according to a statement from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. This creates two tails: an ion tail of charged particles that follows the solar wind and a dust tail.

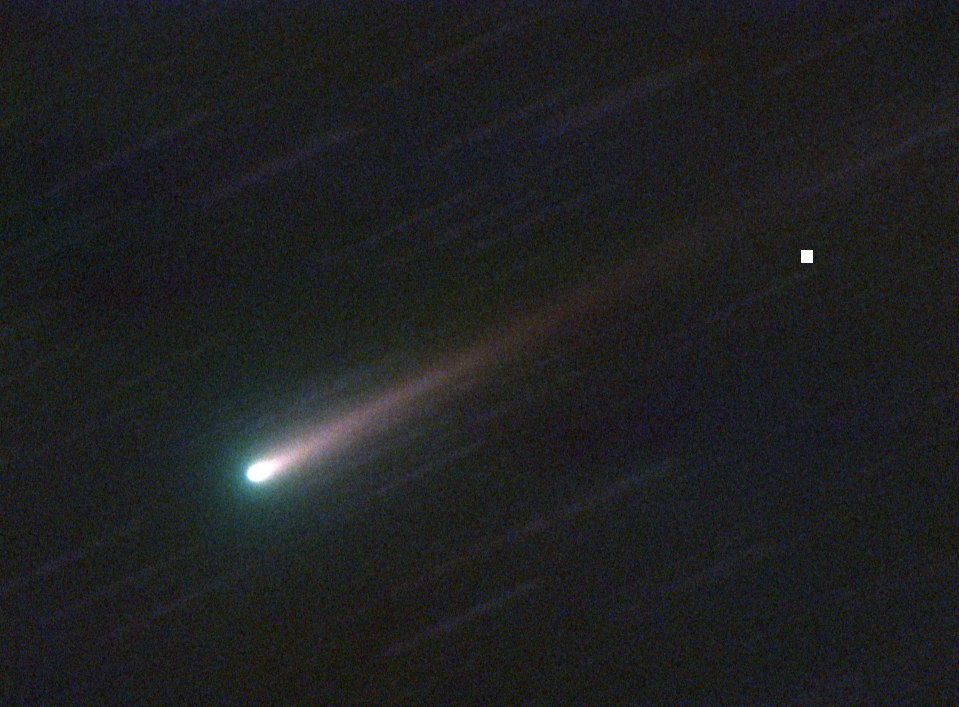

Dust tail rifts have puzzled scientists since at least 1744, when the Great Comet of that year was reported to have six tails — something nobody could explain at the time. That was long before the age of photography, but comet scientists at NASA caught a similar effect on film with Comet McNaught in 2007. [The Greatest Comets of All Time]

McNaught displayed dust bands, or striations, that stretched behind the comet for at least 100 million miles (160 million kilometers) — more than the equivalent distance between Earth and the sun.

The tail so weirded out researchers, according to the statement, that when the first images of McNaught from space beamed down from the STEREO (Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory) mission in January 2007, the team thought something was wrong with the camera. But the tail was real, and it was confirmed in observations from the joint NASA-European spacecraft Ulysses the following month. Later in 2007, Southern Hemisphere observers on Earth got to see the bands for themselves, stretching across the sky and giving a show to the naked eye.

"McNaught was a huge deal when it came, because it was so ridiculously bright and beautiful in the sky," Karl Battams, an experienced professional comet observer with the Naval Research Laboratory who was part of the STEREO team, said in the statement. "It had these striae — dusty fingers that extended across a huge expanse of the sky. Structurally, it's one of the most beautiful comets we've seen for decades," Battams added.

A decade later, a separate research team finally came up with some clues for McNaught's weird behavior. Oliver Price, a planetary science doctoral student at University College London in the United Kingdom, saw something unique happening in the images.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"My supervisor and I noticed weird goings-on in the images of these striations, a disruption in the otherwise clean lines," he said in the same NASA statement. "I set out to investigate what might have happened to create this weird effect."

It turns out this rift is due to our sun's activity. It appeared to be located in a region of the solar system,located at a certain radius from the sun, called the heliospheric current sheet. This is an intricately-shaped zone where the polarity of the solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles that streams from our sun — can change directions.

That realization, however, puzzled Price and his supervisor even more. Scientists long knew that the sun would have an effect on ions (positively charged molecules) in the comet's tail, but seeing the sun change the structure of a dust tail was something new altogether.

"Dust in McNaught's tail — [with particles] roughly the size of cigarette smoke — is too heavy, the scientists thought, for the solar wind to push around," NASA officials said. "On the other hand, an ion tail's minuscule, electrically charged ions and electrons easily sail along the solar wind."

The pictures of McNaught from space, unfortunately, didn't track the comet during its entire journey as it looped around the sun. The comet was traveling too fast for it to remain in images taken from STEREO and SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory). Price said the datasets on McNaught were excellent, but they were spread out from cameras all over the solar system, making it difficult to see what was really going on in the tail.

He decided to try a new image-processing technique. It put together all of the collected data along with a simulation of the tail's appearance. The simulation included factors such as where the individual dust grains were located, how big and old the grains are, and how long it had been since they left the comet. This work created a temporal map; NASA officials said this kind of map "layers information from all the images taken at any given moment."

In practical terms, this meant Price could watch the dust tail evolve during two weeks. He confirmed it was the heliospheric current sheet that caused the striations. It took two days for the comet to go across the current sheet. While this happened, the dust kept getting jostled out of position by the shifting magnetic field lines. It appears the dust wasn’t too heavy for moving, after all.

"It's like the striation's feathers are ruffled when it crosses the current sheet," team member Geraint Jones, a University College London planetary scientist, said in the same statement. "If you picture a wing with lots of feathers, as the wing crosses the sheet, lighter ends of the feathers get bent out of shape. For us, this is strong evidence that the dust is electrically charged, and that the solar wind is affecting the motion of that dust."

Scientists say the behavior of the dust tail can be extrapolated to dust that formed bodies such as asteroids, moons and planets early in the solar system. So this new analysis of McNaught means that our sun's role during the early solar system still needs more exploration.

A study based on Price's research was published online and will appear in the February 2019 issue of the journal Icarus.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.