Scientists Spot What May Be a Giant Impact Crater Hidden Under Greenland Ice

Earth hides its scars well; the planet has endured countless millennia of eruptions and collisions, but scientists are still stumbling upon the evidence of all that geologic drama.

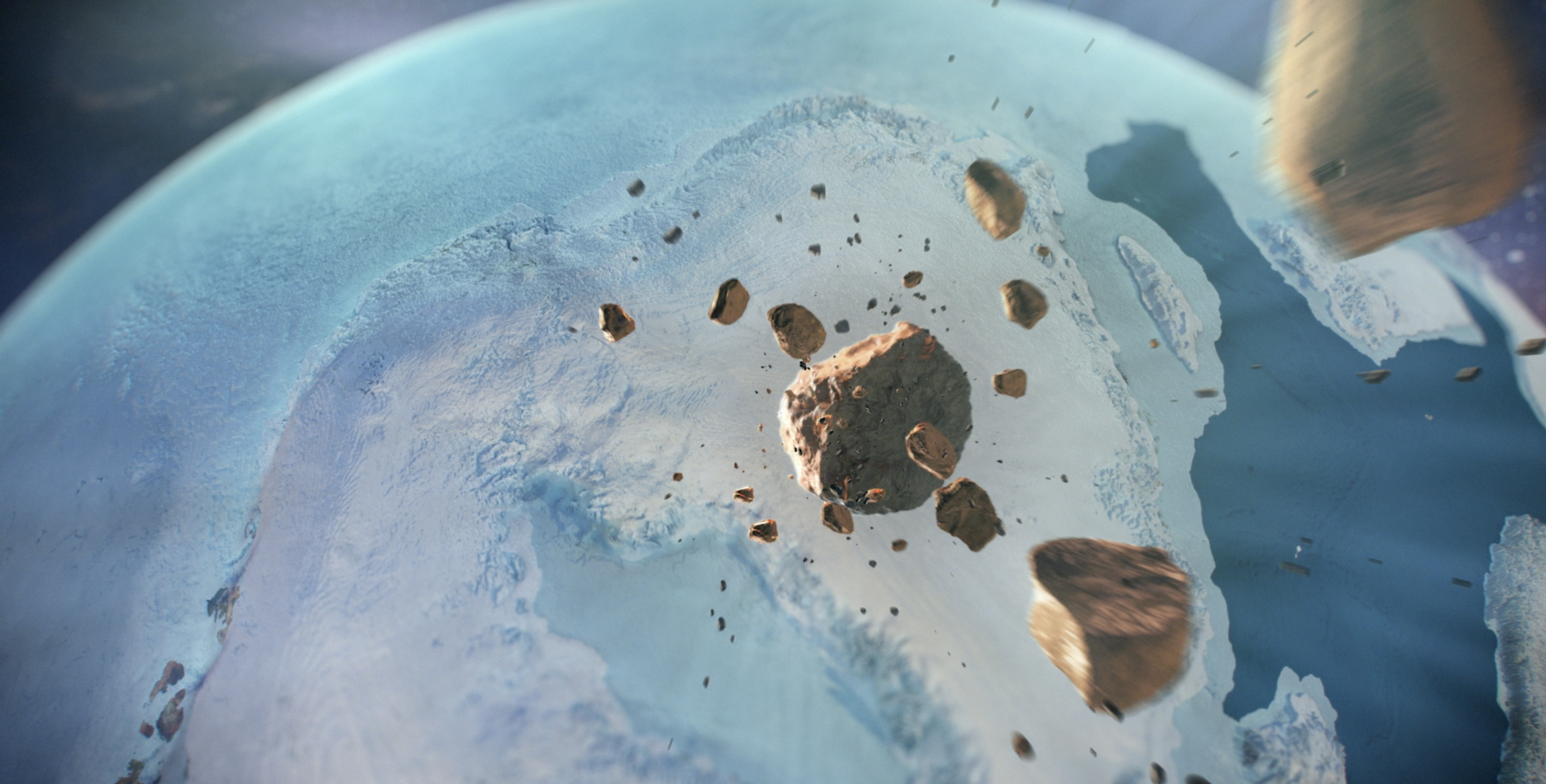

Now, one such team has announced that it spotted a scar hidden below Greenland's ice, a giant crater nearly 20 miles (31 kilometers) wide. The researchers said a giant iron meteorite likely created the mark by slamming into Earth sometime in the past 3 million years.

Other scientists aren't necessarily sold yet that a space rock created the feature. "I think that the authors have presented some intriguing evidence of a possible impact site, and I think that's the right word — intrigued," David Kring, who studies impact craters at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston and who wasn't involved with the new research, told Space.com. "I'm intrigued. I'm not wholly convinced that this is an impact crater." [In Pictures: The Giant Crater Beneath Greenland Explained]

The feature in question is tucked below the edge of the ice sheet in northwest Greenland, lending a semicircular edge to the ice sheet near where a glacier called Hiawatha flows toward the sea. Looking through data originally gathered to track changes in the ice itself, scientists spotted a strangely circular feature in the bedrock, so they arranged for a high-powered ice-penetrating radar instrument to fly over the area.

That instrument's data confirmed the structure of the feature itself: a depression large enough to hold all of Paris in its embrace, with a clearly defined rim all the way around. So, scientists flew in to gather samples in person, looking for chemical fingerprints of an exotic event that could have formed the feature.

And while the glacier blocks the scientists from reaching the heart of the crater, it makes up for that inconvenience by ferrying sediment out from the site in meltwater. "It's almost like a home delivery," Kurt Kjær, lead author of the study and a geologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark at the University of Copenhagen, told Space.com.

Among those sediments, geologists found what they believe are shocked quartz grains, the result of an impact's force abruptly melting rock. The team also analyzed the chemistry of the sample, finding an unusual fingerprint of rhodium, platinum and palladium. "We don't tend to find that in many rocks that we find on Earth," Iain McDonald, a geochemist at Cardiff University in the U.K. who conducted that analysis, told Space.com. "I'm pretty convinced by what's there."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There's another twist to the puzzle of the crater: in Kjær's own institution sits a large iron meteorite that was found about 185 miles (300 km) away from the crater site. Could it be that the meteorite and crater originated from the same incoming asteroid breaking up in Earth's atmosphere as it fell to the surface? "I think it's fair to start speculating if those two are linked," Kjær said. "Maybe we found the home of this meteorite. That would be fun."

But Kring isn't as convinced as the research team that the feature actually has an extraterrestrial origin. "There are thousands, tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of circular structures on the Earth's surface," Kring said. "Almost none of them are impact craters." He said he would also like to see stronger evidence from rock analysis that the feature was truly caused by an impact, rather than by some other process. [Photos: Hunting Meteorites from Florida Fireball in Osceola]

He said he's particularly struck by the apparent lack of any measurable climate upheaval that such a large impact would have caused. The team wants to narrow down the date more precisely with future research but is confident that the crater formed between 3 million and 12,000 years ago, likely on the later end of that range. "It certainly should have created global effects, and we just have no hint or signature of that at this time," Kring said.

(Kjær said that, depending on when precisely the feature formed, it may match the sharp cooling of the Younger Dryas period, which ended about 11,500 years ago, but that it's certainly too early to say.)

Nevertheless, Kring said he's glad the team is pushing forward on ways to identify unknown features on Earth's surface and understand how the planet has changed over time. And if the site does indeed turn out to be an impact, studying it in more detail could offer helpful insight for planetary protection, which considers the potentially devastating effects that future impacts from the ongoing hail of planetary material could cause.

"[Asteroids] are a hazard. They are, in fact, a threat to human civilization," Kring said. "We want to better understand the consequences if or when one of those objects actually hits the Earth, and one way to do that is to go into the geological record and measure those impacts."

For Kjær, what's most exciting isn't even the dramatic collision or its potential successors — it's the act of stumbling upon something unknown. "Look here — the age of discovery is not over yet," he said. "We can still go out here and find things that we didn't see before."

The research is described in a paper published today (Nov. 14) in the journal Science Advances.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.