Superbrilliant Galaxy Got Its Energy by Gobbling Up Its Neighbors

The most luminous galaxy known appears to have devoured three smaller galaxies at the same time, revealing details about why it shone so brightly.

This discovery may help explain how the giant black holes behind such extraordinary light shows reached exceedingly large sizes early in cosmic history, according to the new study.

Supermassive black holes with masses millions to billions of times that of the sun are thought to lurk at the centers of most, if not all, galaxies. When these giants devour matter, previous research suggested they release extraordinarily large amounts of light and likely are the driving force behind quasars — blazing dynamos that are among the brightest objects in the universe. [Behold the Mighty Quasar: The Science Behind These Galactic Lighthouses]

Astronomers can see quasars that shine from the farthest corners of the cosmos, which makes them among the most distant objects known. The farthest quasars are also the earliest quasars to have formed in the universe — the more distant a quasar is, the more time its light took to reach Earth.

Explaining how black holes could have devoured enough matter to reach supermassive sizes early in cosmic history has proved to be extraordinarily challenging for scientists. As such, researchers want to examine as many early quasars as possible to learn more about their growth.

For this new study, scientists focused on the quasar WISE J224607.57−052635.0, located about 25 billion light-years from Earth. This galaxy is relatively small — only about a tenth as wide as the Milky Way, study lead author Tanio Díaz Santos, an astrophysicist at Diego Portales University in Santiago, Chile, told Space.com.

However, this small, dusty quasar is the most luminous galaxy known. It blazes about 10,000 times more brightly than the Milky Way and more than 100 trillion times more brightly than the sun, study co-author Andrew Blain, an astrophysicist at the University of Leicester in England, told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

WISE J224607.57−052635.0 is also among the earliest known quasars, dating back 12.4 billion years, just 1.3 billion years after the universe was born in the Big Bang. WISE J224607.57−052635.0 and its brethren are collectively known as hot, dust-obscured galaxies, or Hot DOGs for short, the researchers said.

The scientists analyzed WISE J224607.57−052635.0 using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico. They detailed their findings online today (Nov. 15) in the journal Science.

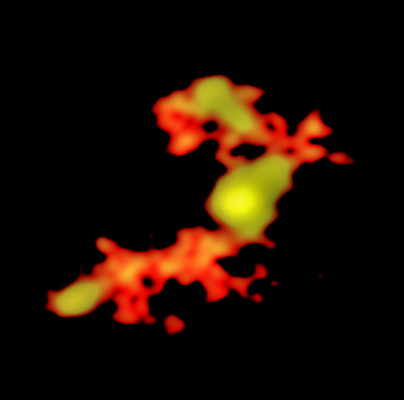

Blain's group discovered three small galaxies linked with the quasar via bridges of carbon-rich dust similar to diesel soot. "These galaxies and bridges extend over a region of space around W2246 that matches approximately the size of the Milky Way," Blain said.

The amount of dust in the quasar alone was equal to up to 1.7 billion times the mass of the sun, and its satellite galaxies contained at least as much dust in total. "We believe this is the first detection of dusty streamers connecting galaxies in a multiple merger event at such an early cosmic time," Díaz said.

The elements in this dust are produced and scattered around galaxies by nuclear reactions within giant stars. This suggests that the gas seen around this quasar was linked with star formation before its dramatic flare-up of light, a finding that could help illuminate how gas and dust help build galaxies, Blain said.

The researchers suggest that mergers between galaxies and smaller companions might not only supply the raw material to power bright quasars but also provide large amounts of dust to obscure it. As such, these findings might help explain the appearance of these bright, dusty galaxies early in cosmic history, they said.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us