The Milky Way's Reflection Shines on Surface of the Moon in Stunning New Image

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

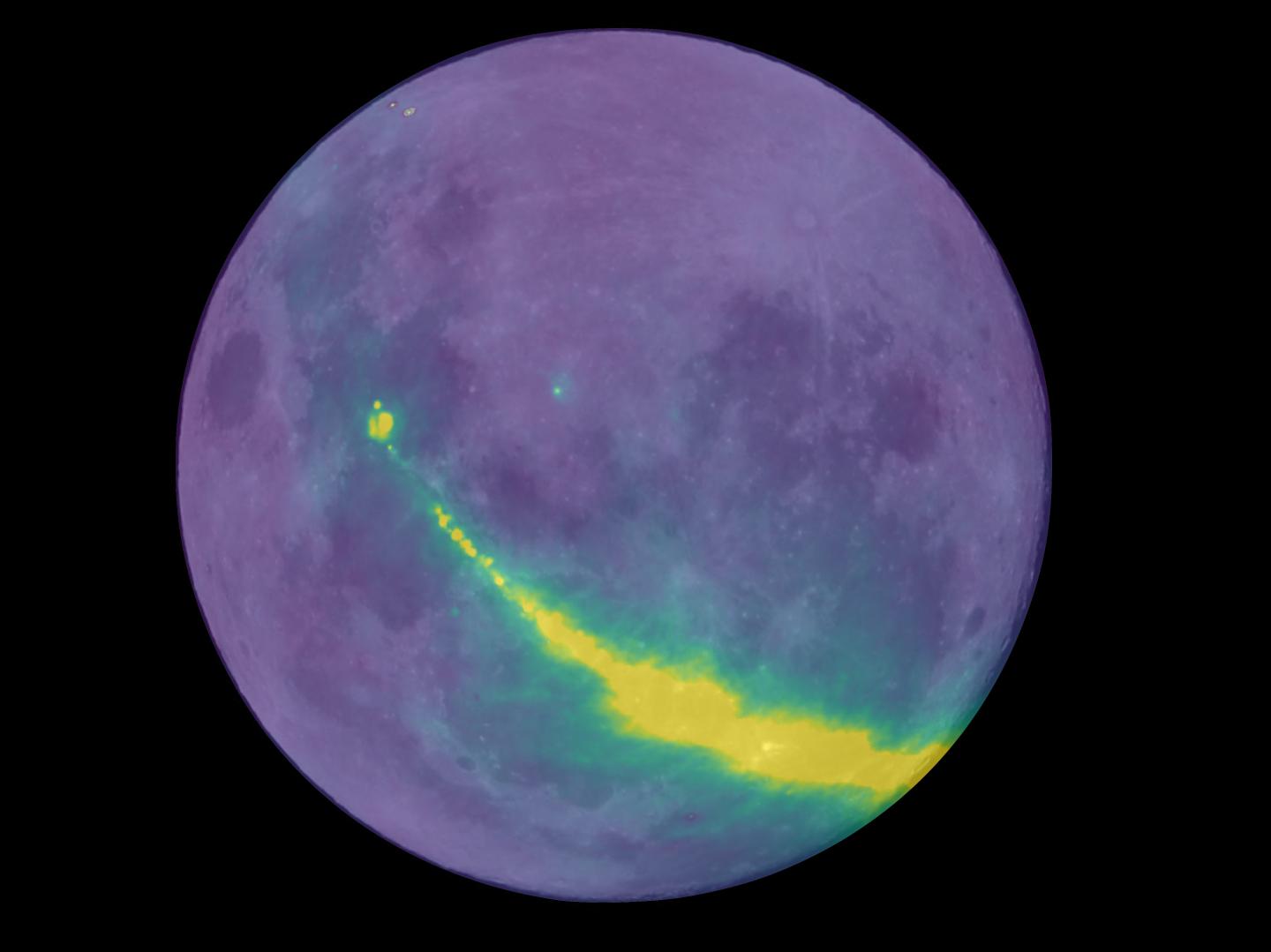

Radio waves from our Milky Way galaxy are reflected across the surface of the moon in a stunning new image.

Using the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) radio telescope in the Western Australian desert, astronomers modeled this stunning view of the Milky Way's radio waves cast across the moon. Researchers will use this measurement to very precisely measure the patch of sky covered by the moon, which will let them eventually detect extremely faint emissions from hydrogen atoms to help see how the first stars and galaxies of the early universe evolved, the research team said in a statement.

"Before there were stars and galaxies, the universe was pretty much just hydrogen, floating around in space," Benjamin McKinley, lead astronomer of the study from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said in the statement. "Since there are no sources of the optical light visible to our eyes, this early stage of the universe is known as the 'cosmic dark ages.'" [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)]

The new image is actually comprised of measurements from the MWA's lunar observations, as well as the Global Sky Model — a map of diffuse galactic radio emission published in 2008. Using computer modeling, the Global Sky Model was mapped onto the face of the moon, allowing astronomers to calculate the average brightness from the Milky Way that would reflect off its surface.

The Milky Way radiates light onto different areas of the moon's surface. This light is then reflected back toward Earth and captured in the telescope's view. Therefore, the researchers were able to calculate how much light from the Milky Way reflects off the moon to factor into their computation, McKinley told Space.com in an email.

Similar to how a car stereo converts radio waves into sound, the MWA radio telescope converts radio signals from space into images, McKinley said.

However, radio signals from the early universe are very weak compared to the other bright objects in the foreground, and standard techniques are not sensitive enough to detect such emissions, according to the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Therefore, the astronomers used the moon as a reference point of known brightness and shape from which the team could measure the patch of sky covered by the moon.

"So to use this technique, we need to assume that we know both the shape of the moon and its intrinsic brightness — and how that varies with frequency," McKinley said. "We can calculate how bright the moon's radio emission should be [based on] its temperature. Then, from our measurements we can deduce the occulted background temperature, which is dominated by radio emission from the Milky Way."

However, the brightness of the moon is influenced by reflections from the rest of the Milky Way — which they factored in by simulation — as well as "earthshine," radio waves from Earth that bounce off the moon and interfere with the signal received by the telescope.

Factoring in this bright interference, the team was able to measure the radio signals of the sky surrounding the moon, McKinley said.

Using this method, the team hopes to detect the extremely faint signal emanating from the hydrogen atoms in the very earliest days of the universe. However, more data and refined techniques are needed, the researchers said.

"If we can detect this radio signal it will tell us whether our theories about the evolution of the universe are correct," McKinley said in the statement.

Their findings were published Sept. 6 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.